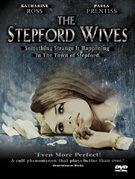

The Stepford Wives

| (Warning: As it is impossible to have a meaningful, critical discussion of The Stepford Wives without giving away its best secrets, this review contains numerous plot spoilers. If you haven't seen the movie, stop reading, go watch it, and then come back. For those of you who have already seen it, read on ...) When it was first released in 1975, The Stepford Wives was described by many feminists as being misogynistic—that it was a cruel male fantasy about stripping women of their identities and making them fully subservient to men. That description could not be any more wrong. In fact, The Stepford Wives is quite the opposite: It doesn't hate women, it hates men. Granted, women are the victims here, and the film does not feature a happy ending of female redemption. However, when you really look at what the film is saying, it is telling its audience that women are strong, women are smart, and, most of all, women are threatening to men, who are essentially unattractive, insecure wimps who would rather replace intelligent females with brainless automatons who will cook for them, clean for them, and tell them they're good in bed, even when they're not. The key to understanding the movie's true message is not found in the surface winners and losers; it's in how the two genders are portrayed. This may be one reason why so many feminists despised the film, namely because they were trying to get away from a feminism that blamed men for all their problems. The screenplay (credited to William Goldman, Oscar-winner for 1969's Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and 1976's, All the President's Men, even though it was reworked by director Bryan Forbes) was based on a 1972 novel by Ira Levine, who also wrote the book on which Roman Polanski's Rosemary's Baby (1968) was based. The two films have a great deal in common, especially in their evocation of impending horror by presenting a bland, everyday world and suggesting that sometimes is slightly off-kilter. The two films are also similar in how they employ selfish husbands who, for their own gain, secretly exploit their dedicated wives at the woman's expense. Much like the Mia Farrow character in Rosemary's Baby, Katherine Ross portrays a normal woman who senses that something is wrong with her surroundings and is unsure of whether it is reality or all in her head. Through the accumulation of intuition that something is not right and the panic of possible insanity, British director Bryan Forbes gives The Stepford Wives an inner tension that keeps it interesting and involving. Whether or not you see this film as a cautionary fable about the modern woman's fear of being subsumed by a dominant male culture, it still works as a good thriller with a bizarre sci-fi twist at the end. The film opens with Joanna Eberhart (Ross), her husband Walter (Peter Masterson), and their two young children leaving Manhattan to live in the small, picturesque town of Stepford, Connecticut. Joanna is an aspiring photographer who is not much of a house keeper, which puts her in immediate contrast with the other married women in Stepford, all of whose lives seem to revolve around baking, ironing, and scrubbing the kitchen counters until they shine. Joanna finds friends in two other women who have recently moved to town with their husbands, the feisty and energetic Bobbie Markowe (Paula Prentiss) and Charmaine Wimperis (Tina Louise), a beautiful redhead who fears her husband never loved her and only married her for her looks. When Joanna, Bobbie, and Charmaine try to get together a women's support group to counter the mysterious Men's Association of which all their husbands are all members, they find no interest from the other women in town. Why? Because the other women are so busy cooking and cleaning and making sure their make-up is perfect. When they finally do get a group together, Joanna wants to talk about her feelings and the problems in her marriage, while the other Stepford wives begin to discuss the extensive merits of Easy-On spray starch. The scene plays like a deranged commercial, and it is funny and creepy at the same time. The upshot of the film is that the Stepford wives are, in fact, not women; they are bloodless, soulless robots, created by the men in Stepford to replace their presumably intelligent and enterprising wives who might see more to life than getting the upstairs floor to a glistening shine and having sex whenever their husbands desire it. Much is made of the fact that the women in Stepford had once belonged to a popular feminist group, which shows that, prior to their replacement, they had been independent thinkers. This is one of the keys to the film and the understanding that it does not look down on women. The real women, the flesh and blood human beings, were smart, while their robotic replacements don't know the meaning of the word archaic. The robots are simply a twisted male fantasy of the ultimate woman: sexy, submissive, and mentally vacant. That this fantasy is pathetic in the extreme says much about the film's view of the male animal and his capacity for feeling and imagination. Notice how the members of the Men's Association are portrayed: All of them are average-looking at best, and not particularly interesting people. Walter is a slouch who drinks too much and is going bald. Another man has a lisp that makes him seem feeble and verbally inadequate. Much is made of how goofy the local pharmacist looks. This underscores how essentially weak these men are in human terms. They are sad and impotent, plain and nondescript with their Izod sweaters and cookie cutter haircuts. They must create fake women who will tell them they are sexually potent because they are incapable of giving real women sexual satisfaction. They are only powerful through their use of technology, which gives them the ability to replace strong, independent women with nonthinking clones who will praise them no matter what. The movie, therefore, suggests that the men cannot deal with women on their own terms—that is, they cannot impress them intellectually, emotionally, or spiritually. They have to literally kill the women and replace them with robots in order to raise their own sagging egos. The Stepford Wives certainly reflects the time in which it was made. It came out in 1975, a time when the Women's Liberation Movement was at the peak of its power (thus, at its most threatening to conservative-minded men). I don't know if this film would work as well in a contemporary setting where feminism has almost become a dirty word. It seems like today, many women have found a workable balance between work and family, which are not seen so much as conflicting opposites, but as two sides of the same coin that must simply be combined in some kind of harmony. Still, The Stepford Wives contains a number of timeless scenes that are the essence of women's fears about the patriarchal society in which they live. The final scene, taking place in a supermarket with all the Stepford wives pushing grocery carts, beaming vacantly with perfect hair and make-up, dressed to perfection in pastel sun dresses and matching hats, is a kind of creep-inducing summation of suburban blandness—the ultimate expression of the modern woman reduced to the lowest common denominator. They are nothing more than bodies who are made up to please their men, doing chores to support their husbands' successful careers. That they are not real in the human sense makes the metaphor complete because, as the film suggests, it is only through death and literally recreation through the hands of selfish, pathetic men that women like this could be created. It is not their natural state, while it is the natural state of men to be overpowering and self-absorbed. That is why the film hates men.

Copyright © 1999, 2001 James Kendrick | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3)

(3)