Paper Moon (4K UHD)

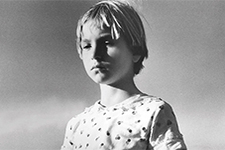

|  Tatum O’Neal was nine years old and had never acted in her life when she played one of the lead roles in Peter Bogdanovich’s Paper Moon opposite her father, then superstar Ryan O’Neal, and became the (still) youngest person to ever win an Oscar. Some have seen her victory as a sentimental fluke, but watching Paper Moon, it is impossible to deny the power and subtlety of her performance and how it avoids all the traps and cloying pitfalls into which so many child actors fall (she has been well described as an anti-Shirley Temple). She and Ryan O’Neal develop a brilliant, absolutely convincing rapport throughout the film, whether they’re arguing heatedly about the merits of Franklin Roosevelt or stealing quick glances at each other that suggest there is much more emotional connection between them than either one would ever admit out loud. Paper Moon is set in the dusty, chalky backroads of rural Kansas circa 1935. It is a funny-sweet story about hard times and desperate people, and it has a genuine heart that makes even some of its most cliché moments ring true. Bogdanovich was at the top of his game when he made the film, having just scored two critical and commercial hits with the bittersweet The Last Picture Show (1971) and the screwball homage What’s Up, Doc? (1972). He was, at the time, a director who couldn’t miss, but Paper Moon turned out to be his last certifiable hit of the 1970s before his career slide began with his critically derided Henry James adaptation Daisy Miller (1974) Ryan O’Neal’s character, Moses Pray, is an itinerant con man roaming through the Depression-era Midwest trying to make a few bucks off recent widows by selling them Bibles he claims their recently departed husbands ordered for them. He meets his match in Addie Loggins (Tatum O’Neal), a headstrong nine-year-old orphan who may or may not be his daughter (“We got the same jaw,” she declares, and they do). Although Moses is only supposed to drive Addie to the next state and drop her off with her aunt, he learns that she is a quick study and a devious little con artist herself, and, despite their initial friction, they team up into an unlikely maybe-father/daughter grifter team (the fact that it is never revealed for sure if he is her father is one of the movie’s greatest and most affecting charms). The screenplay by television-turned-movie scribe Alvin Sargent—who would go on to win Oscars for Julia (1977) and Ordinary People (1980)—from the popular novel Addie Pray by Joe David Brown, has a meandering, easygoing quality to it. It is composed largely of a series of loosely connected comical adventures that slowly develop the relationship between Moses and Addie, which veers from contentious to affectionate. At one point, Moses picks up a big-breasted floozy named Trixie Delight (Madeline Kahn at her ditzy-sad best), and Addie feels so threatened that she has to devise an elaborate scheme to break them up. The last third of the movie involves a protracted grift in which Moses sells a bootlegger $650 of his own booze and incurs the wrath of the bootlegger’s corrupt policeman brother (both characters are played by John Hillerman, who had played bit roles in both of Bogdanovich’s previous films). And, while the backdrop of America at its economic worst always looms large, Bogdanovich never lets it overwhelm the characters, instead allowing it to stand as a stark, constant reminder of how hard times can simultaneously bring out the best and the worst in people. We see this in particular with Moses, who never renounces his life as a conman due to his relationship with Addie (in fact, he embraces it even more as they become partners in crime), but becomes demonstrably more affectionate and open, embracing the fatherhood that may or may not be biologically his. Cinematographer László Kovács, who worked with a veritable who’s who of New American Cinema directors throughout the 1970s, including Dennis Hopper, Hal Ashby, Bob Rafelson, and Martin Scorsese, utilized high-contrast black-and-white photography and deep focus to make the flat landscape and arching sky feel as gritty and real as true life (the fact that he was not even nominated for an Oscar was a grave oversight). As in The Last Picture Show, the use of black and white brings us closer into the era, both narratively and stylistically; Paper Moon looks like it could easily be a John Ford road comedy from 1940. Bogdanovich was a film scholar and historian before he was a director, and he knew exactly how to capture the essence of a bygone cinematic era and still make it relevant to a modern audience.

Copyright © 2025 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © The Criterion Collection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3.5)

(3.5)