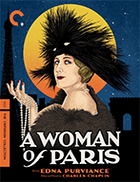

A Woman of Paris

|  Charles Chaplin’s A Woman of Paris is a great example of a mediocre story redeemed by superb filmmaking. Chaplin made it at a particularly crucial point in his career, as he had already achieved vast international success as an actor and director in one- and two-reel comedies and had recently moved into the realm of feature films (which, in the early 1920s, was still a relatively novel concept in Hollywood). He had starred in and directed his first feature The Kid (1921), which was a huge success, as well as The Pilgrim (1923), which was really more of a glorified two-reeler. Even more importantly, he had recently broken away from the Hollywood establishment by forming his own studio, United Artists (UA), with fellow director D.W. Griffith and actors Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks. A Woman of Paris was the first film Chaplin made for UA, and rather than going back to the well of previous success, he gambled by not only making a melodrama instead of a comedy, but also staying behind the camera. As Chaplin biographer David Robinson put it, “He used his new independence to fulfill an old ambition.” Chaplin had already fulfilled that “old ambition” to some degree in his previous comedies, notably The Kid, which has as many moments of genuine dramatic pathos as it does outright comedy (although it still has Chaplin on screen as the indelible Tramp character). With A Woman in Paris, Chaplin left himself off screen entirely (well, not entirely—he does have a brief, humorous cameo as a train porter, but almost no one at the time recognized him). Instead, he decided to write and direct a film centered around a character played by Edna Purviance, with whom he had co-starred in 32 of his previous films, beginning with The Pawnshop (1916). Chaplin intended A Woman of Paris to be a star vehicle for Purviance, about whom he felt a great deal of affection and respect, that would launch her into a new career in dramatic roles. Unfortunately, the film’s failure at the box office—it turned out that audiences didn’t really want to see a Chaplin drama in which he didn’t appear—largely ended her career, as she only appeared in a handful of subsequent films, the French drama Education of a Prince (1927) by Henri Diamant-Berger being the only one not associated with Chaplin as either producer or director. A Woman of Paris’ box-office failure doomed it to relative obscurity for decades because Chaplin pulled it and kept it out of circulation for more than 50 years. It was enormously successful with critics, who recognized that Chaplin was pushing at the boundaries of traditional screen drama, using a relatively rote love-triangle-in-high-society storyline to experiment with how the nuances of human psychology and emotion could be conveyed on screen. The story was inspired primarily by Peggy Hopkins Joyce, a notorious woman for whom the term “gold digger” was coined to describe her skill at marrying millionaires (she was married six times). Chaplin was introduced to Peggy by director Marshall Neilan, and he had a brief affair with her that was long enough for him to absorb many of her wild romantic tales, including one about a young man who committed suicide rather than live without her. Peggy became the model for Purviance’s character, Marie St. Clair, who we first meet as a simple girl living in a rural French village with her domineering step-father (Clarence Geldert) and mother (Lydia Knott). Marie is engaged to Jean Millet (Carl Miller), but their plans of eloping one night are sabotaged by Jean’s possessive mother (Lydia Knott) and the unexpected death of his father (Charles French). So, rather than eloping, Marie heads out to Paris alone. We then jump forward a year to find that Marie is now a prominent Parisian socialite, spending her evenings with various wealthy men about town, particularly Pierre Revel (in indelible, scene-stealing Adolphe Menjou), and wiling away the days with her friends, Fifi (Betty Morrissey) and Paulette (Malvina Polo). Her casual, decadent life is upended by the return of Jean, who moves to Paris with his mother in the hopes of becoming an artist, which forces Marie to reckon with her past and decide on a future of either continued romantic dalliances that keep her in wealth and privilege or a life with Jean that might thrust her back into obscurity and poverty. All of this is standard 1920s melodrama, especially the will-she-or-won’t-she conundrum in which Marie finds herself, but Chaplin redeems its familiarity with a visual and performative approach to drama that helped redefine the genre (Ernst Lubitsch cited A Woman of Paris as a major inspiration on his filmmaking). This is particularly true of the way he directed his actors, drawing from them subtle degrees of emotional nuance that was rare at the time. Chaplin was infamous for doing dozens, sometimes hundreds, of takes, and whereas previously that had been primarily in the service of making a scene as funny or poignant as possible, here it was to get just the right arch of an eyebrow, shift of body posture, or enunciation of a word (unlike many silent film directors, Chaplin was insistent that his actors say their actual lines of dialogue, despite their voices never being heard). The film was shot by cinematographer Roland Totheroh, who had collaborated with Chaplin on most of his films since Work in 1915, including his famous shorts The Immigrant (1918), A Dog’s Life (1918), and Shoulder Arms (1918), as well as all of his features from The Kid through Monsieur Verdoux (1947). He and Chaplin take a relatively spare visual approach, eschewing any expansive camera movements or overly dramatic effects in favor of directness and economy; this is particularly true of the most famous moment of visual ingenuity, when they create the illusion of a train arriving as Marie watches from the platform with nothing more than an off-screen spotlight and cardboard cutouts. The problem, though, is that all the cinematic mastery in the world can’t quite make us forget how fundamentally rote the story is. Chaplin does come up with a rather brilliant and unexpected denouement, one that flies in the face of conventional wisdom and rejects the two most obvious conclusions that would have been expected at that time. But, too much of the story relies on tired contrivances of sophisticated upper-class melodrama, as well as characters who, despite being charming and erudite, are not particularly likeable (Marie is by far the most fully rounded character, and the scene in which she tries to play down her learning that Pierre is engaged to someone else is a masterclass in performance). Much of the narrative also hinges on events outside of the characters’ control (it was originally subtitled A Drama of Fate), which makes them feel at times like puppets on a cruel stage. I wonder if the film wouldn’t have been more interesting had Chaplin focused on the narrative’s great elision—what happened to Marie between boarding the train and walking into a club on Pierre’s arm a year later. Chaplin very purposefully omits her transition from naïve, romantic country girl to cynical gold digger, but I can’t help but think that the better, more compelling story lies in that black hole.

Copyright © 2025 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © The Criterion Collection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3)

(3)