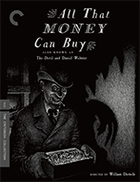

All That Money Can Buy (aka The Devil and Daniel Webster)

|  The devil has been played on screen by a lot of actors over the years—Claude Rains, Vincent Price, Peter Cook, Jack Nicholson, Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, Peter Stormare—and each has given Satan his (or, in some cases, her) own vibe. However, if I were to pick the devil’s greatest screen incarnation, it would have to be Walter Huston’s leering, egotistical Mr. Scratch in William Dieterle’s All That Money Can Buy (aka The Devil and Daniel Webster). In his engaging and unsettling performance, Huston conveys snake-oil charm and seedy menace with a wide, toothy grin, a Popeye squint, and vigorous cigar chomping. His voice has a rough, lilting quality that tells you he is lying even as he draws you in with his brash mixture of confidence and charisma. His brand of evil incarnate is interlaced with old bromides and folk humor, and the brilliance of Huston’s performance is that he makes Mr. Scratch feel like any other character who might be walking the street in the film’s 1840s New England setting even though he is clearly a supernatural entity. It’s uncanny. Of course, Huston’s performance is aided and abetted by Dieterle’s superb direction, Bernard Herrmann’s disquieting, Oscar-winning score, and the expressionist cinematography by Joseph August, a 30-year veteran who had worked with Howard Hawks, George Cukor, and Dorothy Arzner. Dieterle had emigrated from Germany along with so many others in the early 1930s, and his first decade in Hollywood was marked with numerous successes, including The Story of Louis Pasteur (1936), for which Paul Muni won a Best Actor Oscar; The Life of Emile Zola (1937), which won the Oscar for Best Picture; and The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939), which was a major financial success and the first of Dieterle and August’s three collaborations (the third being 1949’s Portrait of Jennie). Just look, for example, at the way Mr. Scratch emerges from the corner of the main character’s barn, stepping out of a web of light shafts as if he had suddenly materialized from the very darkness in-between. Dieterle and August paint in shadows, drawing them out, stretching them, distending them, and at times using them as stand-ins for Scratch to convey his ominous presence looming over a character without actually showing him. Dieterle also employs some notable visual tricks, particularly a few, nearly subliminal cuts to unnerving, negative close-ups of Scratch when Jabez is at his most desperate and, therefore, most vulnerable. Much has been made of the fact that All That Money Can Buy was produced by RKO right after Orson Welles completed Citizen Kane (1941) and the influence that film must have had on it, especially since they share an editor (Robert Wise), art director (Van Nest Polglase), costume designer (Edward Stevenson), special effects designer (Vernon L. Walker), and composer (Bernard Herrmann). As historians have pointed out, RKO, being the newest of the major studios and having to compete with fewer resources, was more open to experimentation and innovation in the late 1930s and early 1940s, which explains why Welles was able to get away with what he did in Kane and why Dieterle, who had recently left Warner Bros., was able to do what he did with All That Money Can Buy. That doesn’t mean that the film was an easy production, though. Its distribution history is a mess, with it being previewed and screened under four different titles over the years: Previewed as Here is a Man at 109 minutes, it was released as All That Money Can Buy in 1941 at 106 minutes and then re-released in 1943 as The Devil and Daniel Webster before being hacked down to 84 minutes for a 1952 reissue under the title Daniel and the Devil. Unfortunately, it was that last version that audiences knew for the next 40 years, as it wasn’t until 1991 that the film was reconstructed in its 106-minute version and released by The Criterion Collection on laserdisc (in his liner notes for the Criterion laserdisc, film historian Bruce Eder describes it as “one of the most harshly handled movies of its era”). Based on the short story “The Devil and Daniel Webster” by Stephen Vincent Benét, All That Money Can Buy is a distinctly American riff on the Faustian bargain, although this time, instead of an already successful protagonist who simply wants more, we have a desperate one who, at his most despairing and angry moment, is willing to give up his soul for just a little success. Thus we are introduced to the young New Hampshire farmer Jabez Stone (James Craig), who is the bearer of more than his share of rotten luck. On a particularly bad day when just about everything has gone wrong, including his devoted wife Mary (Anne Shirley) being injured and his spilling a precious and expensive bag of seed, Jabez blurts out “That’s enough to make a man sell his soul to the devil, and I would for about two cents!” And, on cue, enters Mr. Scratch, who tempts Jabez with seven years of good luck, which he promptly delivers via the sudden appearance of a cache of gold coins that emerges from out of the hay. After that, Jabez’s life is dramatically altered, as he becomes the recipient of such immense good luck that he is soon the wealthiest man in the county, living in a huge manor, loaning money to other farmers, and ignoring his family (including his young son and his tough-as-nails mother played by Jane Darwell). He is lured into the arms of Belle (Simone Simon), a sultry maid who is clearly one of Scratch’s agents (Simon would go on to play the conflicted Irena in Jacques Tourneur’s masterful Cat People for RKO the next year). We know he is going down the wrong path because, immediately after falling into Scatch’s clutches, he rejects membership in the local farmer’s association, thus asserting himself above those in his community (“I look out for myself!” he bellows). And that, as it turns out, is Jabez’s biggest sin, which marks the film as a progressive testament to the importance of community over individual achievement and wealth. Scratch’s use of the term “luck” is heavy with quotation marks because here luck is just another word for corruption and malfeasance; there is nothing “lucky” about Jabez’s inordinate wealth, which aligns his devil-dealing with the American dream of amassing money and power. At the time when people were still struggling out from under the weight of the Great Depression, a story in which an ordinary man turns his back on his fellow farmers and begins to exploit them to his benefit had to sting. When the seven years are up and Mr. Scratch returns to claim what is his, Jabez desperately turns to the famed orator and politician Daniel Webster to defend him. Webster, who is more legend than historical reality here, is played as an amalgam of upstanding rigor and folksy legend by Edward Arnold. Similar to Henry Fonda’s performance in John Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), Arnold makes Webster both larger-than-life and decidedly down to earth. Given to drink and bawdy humor, Webster is recognizably human, and this gives his later speech at Jabez’s trial, which is overseen by “a jury of the damned” that includes the ghosts of Benedict Arnold and Captain Kidd, real punch. His words are lofty and idealistic, but also heartfelt in a way that cuts through any sense of simplistic, kitschy Americana grandstanding. Any such grandstanding is also undercut by Scratch’s defiant declaration that the “dastards, liars, traitors, knaves” of the jury are “Americans, all.” Even more damning is how he claims American citizenship because he was present at the site of America’s worst sins: “When the first wrong was done to the first Indian, I was there. When the first slaver put out for the Congo, I stood on the deck” (one can’t help but hear the echo of The Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil,” where Satan boasts about his presence at various moments of atrocity in human history). What Scratch has to say stings because it’s true, but there is also beauty in what Webster has to say, and the film needs the light it provides given how much darkness has been falling up until that point. Arnold gives a great performance, and his Daniel Webster ensures that Scratch gets him comeuppance—but Huston still steals the show.

Copyright © 2024 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © The Criterion Collection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(4)

(4)