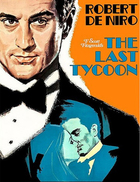

The Last Tycoon

|  The Last Tycoon should have been a triumphant merging of Old Hollywood and the New American Cinema—a silver-screen meeting of Jazz Era literature, Golden Era producing, and modern acting—but the result is anything but. Rather, it is an oddly staid drama that is consistently flat and mannered, much more interesting as a historical artifact than a cinematic experience. The source of the film was an unfinished novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald, which was published posthumously after The Great Gatsby author’s death in 1940, prepared and edited by his friend, the writer Edmund Wilson. Fitzgerald, who spent two unsuccessful months as a screenwriter in Hollywood in the late 1920s, clearly based the novel’s protagonist on MGM’s young head of production Irving Thalberg, a name that would have likely have meant little to mainstream audiences in the mid-1970s (Thalberg died of pneumonia in 1936 at the age of 37). The film’s director, Elia Kazan, was a titan of Hollywood’s Golden Era, having collected Oscars for directing Gentleman’s Agreement (1948) and On the Waterfront (1954)—both of which also won Best Picture and the latter of which was also produced by Last Tycoon producer Sam Spiegel. However, like a lot of directors of his era, Kazan’s career was waning by the late 1960s; while he had earned Oscar nominations for Best Picture and Best Director for his semi-autobiographical drama America America (1964), his last two films, The Arrangement (1969), which was based on his own novel, and the low-budget The Visitors (1972), were critical and commercial failures. The Last Tycoon offered Kazan an opportunity to rise again, especially as it starred Robert De Niro, who had recently won an Oscar for The Godfather Part II (1974) and was riding high on his intense, controversial performances in Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) and Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1900 (1976). Adapted by prolific playwright and screenwriter Harold Pinter (The Servant, The French Lieutenant’s Woman), The Last Tycoon unfolds over several days, following the trials and tribulations of Monroe Stahr (De Niro), the young production head of a major Hollywood studio. He clashes with the studio head, Louis B. Mayer stand-in Pat Brady (Robert Mitchum), does political battle with the head of the writer’s union (Jack Nicholson), manages the narcissistic anxieties of the studio’s leading actor (Tony Curtis), actress (Jeanne Moreau), and screenwriter (Donald Pleasance), and romantically pursues a beautiful, but distant young woman named Kathleen (Ingrid Boulting). When the film is focused on the absurd in’s and out’s of the movie business, it sails along with a winking insider vibe. But, once Monroe sets his sights on Kathleen and the film elevates her as some kind of emblem of unattainable happiness, it sinks quickly into inchoate sentimental murk, leaden with wooden dialogue and distended symbolism (Monroe’s unfinished seaside mansion is an externalization of his unfinished life or empty soul or something). It doesn’t help that De Niro, usually such a powerful screen presence, feels neutered, locked into a character who is so used to holding back that he can’t really express anything. Ingrid Boulting, a Swedish model and dancer-turned-actor is just as flat, but for entirely different reasons. Clearly cast for her conventional beauty and lithe frame, she never conveys anything that would make Monroe step out of his carefully controlled routine, which denies the film a semblance of narrative momentum. Everything just lumbers along, lugging the otherwise beautiful production design and handsome costumes with it (art director Gene Callahan, who won his second Oscar for Kazan’s America America, was not surprisingly nominated for another statue for his work here). In content and approach, The Last Tycoon was hardly unique. In fact, it was a drop in the bucket of a mid-1970s fad among filmmakers both new and old to take all the techniques and expansion of the New Hollywood to render on-screen the Old Hollywood—to pay homage, tribute, and nostalgic accolade to the complicated, messy, glorious cinematic past that helped shape the current moment. To name just a few that were released around the same time as The Last Tycoon: James Ivory’s The Wild Party (1975), John Schlesinger’s The Day of the Locust (1975), Peter Bogdanovich’s Nickelodeon (1976), Arthur Hiller’s W.C. Fields and Me (1976), and Gene Wilder’s The World’s Greatest Lover (1977). Interestingly, almost all of these films were commercial failures that didn’t always do well with critics, either, perhaps because they reeked too much of navel-gazing. It turned out that viewers were less interested in Hollywood history than the filmmakers who wanted to recreate it. However, that isn’t so much the problem with The Last Tycoon, which in its best moments recreates its past era with a remarkable sense of detail and texture. Rather, it sinks under the weight of its flat, inexpressive characters, who fail to evoke the richness of the world they inhabit

Copyright © 2024 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Kino Lorber | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(2)

(2)