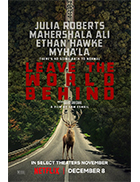

Leave the World Behind

|  There are some things that Sam Esmail’s Leave the World Behind does very, very well. It builds mystery and suspense, sometimes to excruciating levels. It deploys uncanny imagery and surreal touches that turn everyday locations into unnerving threats to the natural order. It reveals the brittle substructure of our supposedly “post-racial” society, where race still matters in some of the worst ways. And it pokes and needles with dexterous precision our deepest anxieties and fears, namely that everything we call “civilization” is precariously balanced on a flimsy stack of cards, and that with the right amount of pressure in the right points at the right time it could all come tumbling down (which was the theme of “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street,” one of the greatest episodes of the original Twilight Zone series). In other words, it presents a bleak, unsettling, all-too-believable end-of-the-world scenario for our tense, paranoid times. However, there are also things that Leave the World Behind does not do very well. It does not present us with particularly interesting characters, instead stranding us with a cross-section of privileged one-percenters who are defined primarily by their bitter misanthropy and lack of self-awareness. It thus fails to give us a good hook outside of its premise, which is intriguing and engaging, but ultimately feels empty without a core of genuine humanity. And it fails to resolve any of the questions it poses. The end of Leave the World Behind is not simply ambiguous and open-ended. Rather, it feels designed to frustrate and irritate in its broad refusal to offer any suggestion behind mere supposition provided by various characters as to what is going on. This last failure is purposeful, and elsewhere it is something I have defended vigorously, as too many films fall all over themselves trying to explain everything as clearly as possible, even when such explanations are completely beside the point (even Geroge A. Romero’s masterful Night of the Living Dead, the 1968 film to which this one owes no small debt, passed off some hokum about space dust on a returning satellite to suggest a rationale for all those corpses coming back to life). But, here the ambiguity feels overly designed, blatantly in your face, as if the film is desperate to propose as many questions as possible by the final reel just to ensure there is more to be unanswered. Take that, mainstream expectations! The ambiguity and open-endedness is the least of the film’s problems, and arguably one that can be spun as its greatest asset—a genuinely brave move against the commercial tide of over-explanation. The film’s real problem is its characters, the people with whom we must spend over two hours watching and wondering if and how the world is coming to an end. Our primary point of reference is the Sandford family: easygoing professor father Clay (Ethan Hawke), high-strung corporate mother Amanda (Julia Roberts), and self-absorbed teenagers Rose (Farrah Mackenzie) and Archie (Charlie Evans). They are upwardly mobile, privileged white Brooklynites who decide to take a last-minute trip to the beach to get away from it. They rent a large house on Long Island for the weekend, but their first day by the shore is violently disrupted when a giant oil tanker inexplicably fails to stop before crashing into the beach. The slow, methodical means by which writer/director Esmail draws out this scene, playing on both the characters’ and our own tendency to think Nah, that won’t happen gives it a stark sense of authenticity and dawning horror. That seemingly freak incident turns out to be a harbinger of things to come, as it becomes more and more clear that something is happening out there. A massive blackout in New York City brings to their doorstep late that night a well-dressed, erudite man named G.H. Scott (Mahershala Ali) and his impatient teenage daughter Ruth (Myha’la). G.H. claims to be the house’s owner, and he is able to provide just enough information to make it seem plausible, which is why Clay is willing to let him and Ruth stay at the house with them despite Amanda’s exasperated wariness that they are not who they say they are (Julia Roberts, who became a superstar in the ’90s with her broad smile, here is pinched and cold and it doesn’t suit her). There is more than a touch of racial tension here, as the Scotts are black and the Sandfords are white; Ruth, in particular, clearly feels that whatever suspicions Amanda harbors are related to her race. From there, things get weirder and weirder, with planes falling from the sky, animals behaving strangely (and in large numbers), self-driving cars going haywire, and an ear-piercing sound exploding at regular intervals (and did I mention no Internet?). There are suggestions of a massive terrorist attack, some kind of inside red-flag operation, or perhaps just the whole world spinning off its axis. Whatever it is, the main characters attempt to go about some form of normal life—drinking wine, lounging by the pool, getting to know each other in ways that might not be appropriate—but it all feels futile, a rearranging of deck chairs on a world that is slipping into the abyss. And, of course, we again run into the film’s fundamental problem, which is that none of these characters are particularly interesting or sympathetic, and in some cases downright off-putting. This, of course, may very well be the point, but it if it is the point, it is a dull one indeed. Hawke’s Clay comes close to being tolerable in his recognizable confusion and desperation, especially when he leaves a desperate woman on the road because he simply has no idea how to help her. Similarly, Ali’s G.H. is potentially sympathetic, although much of the film is designed to keep us in the dark about whether or not he has nefarious intentions, which makes his seeming decency and patience play as a constant cover for something sinister. The kids, meanwhile, are not alright. Myha’la’s Ruth is insufferable in her eye-rolling condescension, and Archie is just a creep (the scene in which he voyeuristically takes pictures of Ruth in her bikini and then masturbates to them that night is just gross and does nothing to build his character unless we are supposed to think of him as a budding sex offender). Based on the best-selling 2020 novel by Rumaan Alam, which was a finalist for the National Book Award, Leave the World Behind is the second feature directed by Sam Esmail, who is best known as the creator of the television series Mr. Robot (I have not seen his first film, the 2014 unconventional romance Comet). It shows a great deal of promise stylistically and tonally, but displays something close to tone deafness when it comes to character and situation. Unless the entire film is meant as some kind of cosmic punishment for self-absorbed rich people who openly wear their disdain for their fellow human beings on their sleeves, it is hard to see what the point of Leave the World Behind really is. Ironically, a running thread in the film is Rose’s obsession with the ’90s sitcom Friends and her distress that the end of the world might keep her from watching the final episode and finding out what happens to the characters in which she has spent so much time investing herself. She wants to know how it ends because she cares about the characters. Leave the World Behind creates the opposite effect. Copyright © 2023 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Netflix |

Overall Rating:

(2.5)

(2.5)