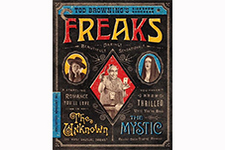

Freaks

|  Fascinating, unsettling, and genuinely touching, Todd Browning’s Freaks is a notorious contradiction of a film. Populated by actors and performers with actual congenital anomalies, including a man with no arms and no legs, another man who walks on his hands because he has no body from the mid-torso down, a human skeleton, a bearded woman, and Siamese twins, it was long misunderstood as a sensationalistic exploitation film, primarily because that was how it was sold. However, when viewed on its own terms, it becomes clear that Freaks is an empathetic drama about the pains of being different and the power of interpersonal bonds. Browning, who had worked in circus sideshows as a young man throughout the 1890s, treats the film’s malformed characters—who are described in the opening sequence by the dour carnival barker as “living, breathing monstrosities”—with a sympathetic touch. Both nature and humankind have turned their backs on them, so they have only each other to lean on. Running just over an hour in length, Freaks was loosely based on (“suggested by,” per the credits) the 1923 short story “Spurs” by horror and mystery author Tod Robbins, whose 1917 novel The Unholy Three had been adapted by Browning as a film of the same title in 1925 (one of his ten collaborations with Lon Chaney). The protagonist of Freaks is Hans, a little person with a broad, child-like face played by Harry Earles, who had previously starred in The Unholy Three and was the one who initially brought “Spurs” to Browning’s attention. Hans works in Mme. Tetrallini’s traveling carnival as one of the sideshow attractions, and like the other “freaks” of the title, he is mostly rejected by the so-called “normal” members of the carnival. Only Mme. Tetrallini (Rose Dione), who refers to the them as her “children,” Phroso, the head clown (Wallace Ford), and Venus, the seal trainer (Leila Hyams), treat Hans and the others with dignity or respect. Although Hans is engaged to be married to another little person, Frieda (Daisy Earles, his real-life sister), his heart is enamored with Cleopatra (Olga Baclanova), a sultry trapeze artist who is involved with Hercules (Henry Victor), the self-absorbed strongman. Cleopatra and Hercules cruelly amuse themselves with Hans’s awkward romantic advances, which include sending her flowers and visiting her trailer. When Cleopatra learns that Hans has inherited a great deal of wealth, she concocts a scheme to marry him and then poison him so she and Hercules can make off with the money. However, Hans learns of her plan, and the carnival freaks band together in a revenge plot that is as horrifying as it is appropriate—“a climax that achieves the texture and imagery of a screaming nightmare,” as Louis B. Mayer biographer Scott Eyman put it. This was not how Browning wanted to end it; rather, he wanted a sad ending that eschewed anything overtly horrific in favor of a focus on the freaks’ unending isolation from regular society. But, he was overruled by the executives at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), who wanted to out-horrify the competition and got more than they bargained for in Browning’s thundering, expressionistic climax. Louis B. Mayer, the head of MGM, was, according to Eyman, appalled by the film. Of course, the fact that Mayer, the powerful head of the largest and most profitable Hollywood studio in the 1930s, had anything to do with Freaks is part of the film’s fascinating history. Irving Thalberg, MGM’s vice president in charge of production, had taken note of Universal’s success with Dracula (1931), which helped lay the groundwork for the then-nascent horror genre. Thalberg wanted MGM to get into the horror game, and he lured Browning, who directed Dracula, away from Universal, signing him to a three-picture deal (Browning had actually been under contract with MGM in the mid-1920s, where he directed some of his most famous collaborations with Chaney, including The Unholy Three and 1927’s The Unknown). Browning was not a particularly stylized filmmaker, which means he was usually content to use a static camera with little editing. He was deeply influenced by German Expressionism, and that is evident in Freaks’ climactic revenge sequence, which takes place during a thunderous rainstorm. Browning builds a real sense of terror and suspense with editing, lighting, and carefully angled shots. He also allows his actors to do much of the work, which we especially see in a scene where Cleopatra, at the dinner following her marriage to Hans, is utterly repulsed by the carnival freaks merrily singing, “We accept you, one of us.” When Freaks was released, the fact that its sympathies are clearly invested in its titular characters was lost on critics and audiences, who viewed them as repulsive and disgusting. They couldn’t—or wouldn’t—see beneath the film’s shocking veneer to recognize that it is actually about looking past the superficiality of physical appearances. Browning’s use of people with genuine physical abnormalities was a gamble here, and one that backfired initially, although it is key to the film’s effectiveness for those willing to see it for what it really is. Browning initially elicits real unease from the audience at seeing the titular freaks, which initially aligns viewers with the “normal” characters on-screen who shun them. Yet, he is later able to draw sympathy for them, because once the initial shock of their predicament wears off, we begin to see them for what they are: real human beings with feelings, emotions, fears, and desires. Physical exteriors, the film insists, are just that—shells in which we exist—and it is sometimes the conventionally beautiful people—in this case, Cleopatra and Hercules—who are the true monsters (which offers a major thematic shift from the short story, where the Hans character is very much a monster). Initial audiences’ misreading of Freaks is at least partly due to the fact that its advertising campaign made no mention of the underlying human emotions. The original release posters asked such sensationalistic questions as “Can a full grown woman truly love a midget?” and “Do Siamese twins make love?,” which cast the film itself as a sideshow exhibit (MGM later tried to market it on humanistic grounds, but by then it was too late). It ended up losing a great deal of money, and it was banned in a number of countries. MGM tried to wash their hands of the film by first burying it for a decade and a half, and then by licensing it for 25 years to exploitation distributor Dwain Esper (Damaged Lives, Maniac, Reefer Madness), who changed the title to Forbidden Love and tacked on a disingenuous opening crawl that attempted to frame it in the same kind of faux-educational discourse that he used for films about drug addiction and venereal disease. Freaks was eventually rescued from exploitation purgatory, initially by European critics and audiences. It was revived in 1962 at the Venice Film Festival, which led to various critical re-evaluations, including an influential write-up in the French film journal Cahiers du cinéma, which notes that the film is “horrific,” but also reveals “warmth and humanity,” and a 1964 piece in Film Quarterly in which John Thomas called it “a minor masterpiece.” Later that decade it was embraced by the counterculture and became a staple of midnight screenings throughout the 1970s alongside other arthouse shockers like Alejandro Jodorowsky’s El Topo (1970) and David Lynch’s Eraserhead (1978). Since then, Freaks has been rightly recognized as one of Browning’s best films and one of the most unique, challenging, and provocative films of the early sound era.

Copyright © 2023 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © The Criterion Collection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3.5)

(3.5)

This two-disc Blu-ray set contains three films: The Mystic (1925), The Unknown (1927), and Freaks (1932).

This two-disc Blu-ray set contains three films: The Mystic (1925), The Unknown (1927), and Freaks (1932).