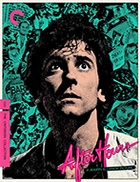

After Hours (4K UHD)

|  There’s really no easy way to put it: The 1980s was a weird period for Martin Scorsese. Bookended by two of his undisputed masterpieces—Raging Bull (1980) and GoodFellas (1990)—the Reagan era was a period of uncertainty, instability, and experimentation for Scorsese, for whom the 1970s was a pinnacle of artistic and critical success with Mean Streets (1973), Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974), and Taxi Driver (1976), which won the Palm d’Or at Cannes. It wasn’t all highs, though, as New York, New York (1977), Scorsese’s love letter to classical Hollywood musicals, was a disaster with critics and audiences. Although he bounced back with the superb concert documentary The Last Waltz (1978) and Raging Bull, the latter of which is widely considered the best film of the ’80s, Scorsese’s cinema was increasingly on the outs in a Hollywood system that was seeking to align itself more with Reagan’s forthcoming “Morning in America” than the political and institutional malaise of the ’70s that had fueled so much of the New Hollywood. Following Raging Bull, Scorsese directed The King of Comedy (1982), a bitter black pill of a film that has developed a strong cult following, but at the time was another commercial failure. He then spent a good chunk of time trying to mount an adaptation of Nikos Kazantakis’s controversial novel The Last Temptation of Christ, which he would eventually do in 1988. But, when that project fell apart in 1983, just weeks before he was to begin production, he turned to an even more unlikely project: After Hours, an absurdist descent into a New York yuppie’s nightmare all-nighter in SoHo. The screenplay was written by an unknown, Joseph Minion, who had originally penned it while a student in the screenwriting program at Columbia University. It found its way into the hands of actor/producer Griffin Dunne, whose producing partner, Amy Robinson, got it to Scorsese. In some ways, After Hours is an anomaly in Scorsese’s oeuvre. Although he included elements of dark comedy and absurdity in many of his films before and since, he had never made an outright farcical comedy. Given his strong association at the time with violent, hard-hitting dramas, the idea of Scorsese directing something as fundamentally ludicrous as After Hours—a trifle of sorts—felt like some kind of cosmic joke. Yet, so much of it clearly resonates with Scorsese’s other work, especially the nocturnal setting in New York City, whose late-night troupe of punk rockers, oddball waitresses, postmodern artists, and overeager neighbors is like a comedic riff on the “animals” that come out at night in Taxi Driver (and, just for good measure, there is plenty of hellish steam escaping from every manhole and storm drain). The air of impending violence and the restless camera are signature Scorsese, although here the camera feels even more restive and addled, as if had been snorting the cocaine that Scorsese had given up after almost dying in 1978. The story centers on Paul Hackett (Griffin Dunne), a disaffected corporate office drone (he does something with word processing in a nondescript Manhattan office filled with other, similarly suited drones). At a coffee shop one night he meets Marcy (Rosanna Arquette), and they connect over their shared love of Henry Miller. She gives him her number, he goes back to his apartment, considers, and then calls her. She invites him over to her apartment in SoHo, and even though it is getting late, he accepts the invitation, which begins his descent into what turns out to be an entire other world, one that Paul is not in any way equipped to navigate or manage, starting with the startlingly rapid cab ride, whose sudden lurching turns causes him to lose his $20 bill, thus leaving him with no money. But, that turns out to be the least of his worries, as he ends up in an escalating nightmare of entrapment in which, no matter what he does, he can’t get home. It is like that nightmare we’ve all had where we’re running but don’t actually go anywhere. Paul’s entrapment in the surreal environs of SoHo at night is amplified by the various characters he encounters, including Marcy’s artist roommate (Linda Fiorentino), a frustrated waitress (Teri Garr), a seemingly well-meaning bartender (John Heard), two thieves (Cheech Marin and Tommy Chong), and a Mister Softee vendor (Catherine O’Hara) who becomes convinced, like much of the rest of the neighborhood, that Paul is a serial burglar. Griffin Dunne, who at the time was best known as the undead best friend in An American Werewolf in London (1981), ably plays Paul’s increasing desperation and incredulity; every time he thinks he is on his way out or has met someone who can help him, things take a turn for the worst. Some of the best scenes involve him and Rosanna Arquette, whose Marcy is gradually revealed to be neurotic in ways that Paul could have never imagined. Their exchanges are awkward and unpredictable, mainly because it is so clear what Paul wants while Marcy is always a wink away from a complete personality shift. The discordant rhythms of their running-off-the-rails would-be romance are the film’s best evocation of screwball pathos, and they generate a kind of anxiety that all the careening camera movements, sped-up cinematography, and slam-bang point-of-view shots can’t quite capture. This is not to say that the style isn’t great—it is. Rather, the film’s primary problem is Paul. Simply put, he is kind of—well, pretty much totally—a cad, which undercuts our sympathy for him. And not just a cad, but a cad in sheep’s clothing. When he drops to his knees late in the movie and cries out to the sky, “What have I done?,” it clarifies his own lack of self-understanding. His ennui is unmoored to any obvious problems other than mundane sameness, and we don’t know much about him outside of the broad strokes we are given regarding his profession and his essential isolation from everyone around him. Yet, when he arrives at Marcy’s enormous SoHo loft only to find Kiki in a bra and leather skirt putting together a papier-mache sculpture, it isn’t long before he is coming onto to her in ways that can only be read as incredibly skeevy. And let’s not even talk about the scene in which he undrapes the body of a recently deceased woman (there is a plot purpose here, but it still feels incredibly insensitive and gross). Dunne certainly works to make Paul into a reasonable everyman lost in a nocturnal vortex of insanity in which everyone and everything seems cosmically stacked against him, but these small moments leave their mark on our sympathies in way that undercut the film’s effectiveness.

Copyright © 2023 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © The Criterion Collection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(2.5)

(2.5)