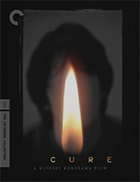

Cure (Kyua)

|  The hypnotist villain of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure (Kyua) is an enigma. A shaggy young man in his twenties, he may be a ghost, or he may be a man possessed, or he may be evil incarnate. Professing to be an amnesiac who sometimes can’t remember what was said 10 seconds earlier, he has a supernatural ability to control the minds of those with whom he comes into contact, and for reasons that are left as maddeningly vague as everything else about him, he asks them to kill. That is the basic premise of Cure, a stylish horror thriller that looks on the surface like a police procedural, but is really an eerie meditation on the self—who we are and how much power we have over ourselves and others. The villain, Kunio Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara), constantly asks those around him, “Who are you?,” and when they respond with the typical answer stating their name or perhaps their profession, he undermines that thin veneer of confidence by stating again, “Who are you?” With the flicker of a cigarette lighter, he draws his victims into his spell and turns them into vicious, unwitting killers. In an age in which violence is increasingly driven by unwavering fundamentalist ideologies, both political and religious, the idea of mind control is a frightening notion, one that carries a great deal of emotional weight. The mind-control scenario in Cure is clearly fantastical, but it still has a core of reality to it that digs into one’s gut. After all, one can certainly argue that suicide bombings and mass shootings and political riots are the result of various forms of mind control, in which one becomes so entranced with an idea that there is seemingly no answer outside of violence. Kurosawa increases the impact by shooting the murders from a dispassionate distance that allows the violence to transpire in real time without a cut, the camera not flinching as a man smashes in a woman’s head with a pipe or a police officer suddenly shoots his partner in the back of the head. These moments of violence are sudden and often shocking, although as the film wears on they begin to accumulate a heightened sense of dread that overcomes the shock of witnessing. Just seeing Mamiya come into someone’s life gives one a sickening sense of apprehension, knowing what will inevitably happen. Much of the film centers on Kenichi Takabe (Kôji Yakusho), the police detective investigating the murders, all of which seem to be random and unconnected except for the fact that the murder victim always has his or her neck slashed in an “X.” When he interrogates the suspects, they always admit to committing the murder, but have no idea why. In one of the film’s most chilling lines of dialogue, one of the unwitting murderers, who has killed his own wife, says, “It just felt natural,” and then breaks down into sobs of anguish. Thus, in Cure, each murder has two victims, as the one who does the deed is destroyed emotionally just as surely as the person he or she killed is destroyed physically. Takabe begins to suspect that hypnosis is the cause of the murders, although it is an idea that is scoffed at because it implies something beyond the ordinary abilities of even the best hypnotists. The case also resonates with Takabe’s own life, as he has to care for his mentally ill wife, Fumie (Anna Nakagawa), who can easily get lost and disoriented, again showing how fragile our sense of self can be. Writer/director Kiyoshi Kurosawa, a genre specialist who had been directing films since the early 1980s, garnered international acclaim for Cure, and many critics have since elevated him to the status of auteur, as his influence can be seen across a wide range of filmmakers, including Ryusuke Hamaguchi (Drive My Car), who studied under him in the graduate film program at Tokyo University of the Arts, and Bong Joon-ho (Parasite), who has cited Cure as one of the greatest films ever made. No doubt—Cure an effective, deeply unsettling thriller that continues to perplex because it refuses the kinds of restorative satisfaction normally supplied by that genre. Kurosawa shows us who the villain is by the first reel; thus, the mystery that fuels the rest of the film is not who he is, but what he is. That question is never quite answered, which reinforces the film’s underlying theme about the ambiguous nature of knowledge, especially in the face of violence.

Copyright © 2022 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © The Criterion Collection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3.5)

(3.5)