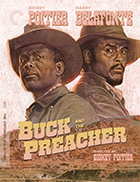

Buck and the Preacher

|  Released amid the flurry of blaxploitation films that all but defined African American cinema in and around Hollywood in the early 1970s, Sidney Poitier’s directorial debut Buck and the Preacher went against the grain, rewriting one of Hollywood’s most storied genres—the Western—through the lens of neglected black history. Although the history books have long told us that at least one in four of the cowboys who worked the range in the late 1800s was African American, Hollywood Westerns had long told a very different story, one in which virtually everyone was white. Buck and the Preacher, which Poitier also produced alongside his friend, collaborator, and fellow star Harry Belafonte, was a means to correct that racial imbalance, which is what led Poitier and Belafonte to fire their initial choice for director, Joseph Sargent, whose take on the material (which was informed by his experience in television, including helming popular oaters like Gunsmoke) was insufficient to the cause. Thus, with Belafonte’s encouragement, Poitier took the directing reins himself, even though he had never helmed a movie before. As it turned out, Poitier was a natural, and the rousing effectiveness of Buck and the Preacher as both entertainment and corrective history belies his inexperience behind the camera. The film was written by Ernest Kinoy (a veteran of ’50s and ’60s television anthology dramas) from a story originally concocted by Drake Walker and shot entirely in Mexico with a mostly Mexican crew (including cinematographer Alex Phillips Jr.). The story takes place in the years following the Civil War when thousands of newly freed slaves were making their way West to start new lives. Poitier, who had achieved immense levels of stardom in the 1960s after winning an Oscar for Lilies of the Field (1963), plays Buck, a former Buffalo Soldier who now works as a wagon master leading groups of black settlers through the harsh western terrain. There are numerous dangers along the way, the worst being bounty hunters hired by Southern plantation owners who attack the black wagon trains as a means of terrorizing the settlers and forcing them back South where they would essentially return to enslavement in the cotton fields. One of the wagon trains Buck is leading is attacked in the night by a gang led by a particularly ruthless bounty hunter named Deshay (Cameron Mitchell), who steals more than $1,000 the settlers had saved to start their new lives. Buck is determined to not only see the settlers through on their journey, but also to retrieve the stolen cash. He is joined on his mission by his wife, Ruth (Ruby Dee), and by Belafonte’s Reverend Willis Oakes Rutherford, a perfidious “minister of the High and Low Order of the Holiness Persuasion Church.” With his rotten teeth, scraggly beard, and shaggy hair, Belafonte is virtually unrecognizable, at least to those who were primarily familiar with him as the smooth, handsome crooner of Calypso classics (Diahann Carroll once called him “the most beautiful man [she] ever set eyes on”). Belafonte had been acting in movies since the 1950s, but as Donald Bogle notes in his seminal critical history of black film Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, & Bucks: An Interpretative History of Blacks in American Film, the roles in which Belafonte had been cast tended to be safe and antiseptic, neutering his personality and sexuality, leaving him “strangely bland and innocuous.” But, in the unlikely role of Preacher, Belafonte “had discovered in himself, at forty-four, a rough-and-ready, gutsy quality that had vitality and delighted audiences.” To be sure, Belafonte is the best thing in the film, as he uses that gutsy vitality to great comic effect without losing the underlying drama of his character arc, which finds him moving beyond Bible-toting chicanery in favor of something genuine and meaningful. For his part, Poitier is willing and ready to play the straight man in the film’s odd couple, although the intensity of Buck’s character marks a crucial shift for Poitier as an actor. The film also offers a unique take on the relationship between black settlers and Native Americans, as Buck must work with a tribe to ensure safe passage and eventually needs their assistance in fighting off the bounty hunters, who represent an existential threat to both groups. Buck’s standing with the tribe is complicated by the fact that he once worked as a soldier in the U.S. Army and is therefore at least partially accountable for the violence against them. And, while it is troubling that the film cast a white actress (Belafonte’s wife, Julie Robinson) as a native woman, there is a clear effort to align the struggles of African Americans and Native Americans in the shadow of a white power structure that wanted to own and obliterate them, respectively (at one point Ruth declares that she no longer wants to live in the United States because it is as if the ground has been poisoned, a stinging assessment of the damages wrought by systemic racism then and now). The decline of the traditional Western in the late 1960s and early ’70s had opened a space for revisionist takes on the genre such as Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969) and Arthur Penn’s Little Big Man (1970), and Buck and the Preacher belongs right there with them, being all the more notable for having been helmed by a black director, which had happened on a major studio production only a few times previously (the first being Gordon Parks’s The Learning Tree in 1967). And, while it is tempting to see Poitier’s Buck as a trailblazing black protagonist, he is really part of a history that stretches back to at least the 1930s, when black cowboys were heroes in the margins of the Hollywood studio system. Harlem on the Prairie (1937) starring Herb Jeffries was billed as the first “all-colored” Western musical, and Jeffries went on to headline a series of low-budget, barely feature-length Westerns with all-black casts, including Rhythm Rodeo (1938), Two-Gun Man From Harlem (1938), The Bronze Buckaroo (1939), and Harlem Rides the Range (1939). Of course, these were light-hearted musicals, and it wasn’t until the 1960s that more serious Westerns included black faces, particularly Woody Strode in Sergeant Rutledge (1960) and The Professionals (1966). However, black actors were typically cast in marginal and supporting roles, which is what made Buck and the Preacher such a watershed moment in the history of the genre and why its triumphant ending with Poitier, Belafonte, and Dee riding across the range after having vanquished the white bounty hunters was such a thrill for black audiences.

Copyright © 2022 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © The Criterion Collection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3.5)

(3.5)