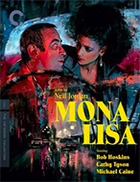

Mona Lisa

|  The title of Neil Jordan’s third feature, Mona Lisa, is not a direct reference to the famous Leonardo Da Vinci painting (although it does make a brief appearance in at least one shot), but rather the 1950 song made popular by Nat “King” Cole that plays over the opening credits and later on a car radio. The song’s lyrics refer to the painting, but in the service of describing a mysterious woman who has clearly enraptured the singer, but remains decidedly enigmatic: “Do you smile to tempt a lover, Mona Lisa? / Or is this your way to hide a broken heart?” The film’s Mona Lisa is Simone (Cathy Tyson), a high-price London prostitute who is chauffeured to her various meets at mansions and five-star hotels by George (Bob Hoskins), a squat, artless East End petty criminal who has been given the cushy assignment as repayment for the seven years he spent in prison to protect Mortwell (Michael Caine), an organized crime boss for whom he worked. As the song suggests, Simone is mysterious and seemingly unfathomable, especially to a small man like George, who is tough, but also a bit naïve. He lacks sophistication and grace, which she has in spades, although his eventual attraction to her is not based on her beauty or her social charms, but rather her vulnerability, which he first witnesses when she asks him to take a detour through one of London’s seamier streets that is crowded by desperate streetwalkers who wear bruises from their pimps and desperation in their eyes. For a while it is unclear why Simone would want to see this, but we eventually learn that it was from this cesspool that she emerged and that she left behind a young friend named Cathy (Kate Hardie), who is still under the control of her former pimp. George, out of devotion and a sense of shared vulnerability (he is being kept from seeing his teenage daughter by his ex-wife), agrees to help Simone look for Cathy, which takes him through the hellish, subterranean world of London’s strip clubs and sex shops and back-alley brothels. Written by Jordan and David Leland (Wish You Were Here), Mona Lisa draws equally and loosely from several interconnected genres, including crime thrillers and romantic dramas, merging them in ways that are both unexpected and moving. Much of the film works out of the sheer force of Bob Hoskins, who won the Best Actor prize at Cannes for his performance as George, a contradictory mess of angry outbursts, sullen resentment, and romantic longing. As Jordan described him, he is an “inarticulate romantic … brutal, pitifully simple, with a beautiful heart.” When he impulsively starts pounding a pimp’s head because he yells at Simone in the back seat of the car, the sudden violence plays as a romantic gesture—his version of giving her flowers. Hoskins keeps the character grounded in his lack of guile and sophistication, which is why he is so humorously out of place in the high-end hotel lobbies where he must wait for Simone to finish her business. He comes from the brutal world of crime, yet he isn’t loathsome even when he’s crass and racist. He is just misguided, which is surely what Simone sees in him. Jordan, whose previous film was the surreal horror-fantasy The Company of Wolves (1984), clearly recognizes the contours of the genres in which he is working because he plays them against each other, staying true to their essence while defying them all the same. He and cinematographer Roger Pratt, who recently shot Terry Gilliam’s satirical Brazil (1985) and would go on to shoot Tim Burton’s Batman (1989), Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein (1994), and Lasse Hallström’s Chocolat (2000), give London an air of both gritty reality and fairy-tale otherworldliness. There are comic interludes scattered throughout and moments of bloody violence, as well as poignant character moments. George has a burly best friend named Thomas (Robbie Coltrane) with whom he is staying, but otherwise he appears to be largely alone in the world, and it is that isolation that connects him and Simone. Cathy Tyson, at the time a 20-year-old stage actress making her screen debut, is appropriately enigmatic as Simone, although she suffers to some degree just in comparison to Hoskins, who commands every moment even when he’s in over his head (which is, frankly, most of the time). Simone is too much like the titular painting—alluring and mysterious and suffused with only the depth that we read into her. Tyson does what she can, but Simone is more of an idea than a character, a set of conceits—another riff on the hooker with a heart of gold and the obscure object of desire—that propel George into a netherworld with which he is (at times comically) unfamiliar and ill-suited. His angry outbursts and insults are childlike because they derive from his frustrations and insecurities, which makes him poignant, unlike Caine’s Mortwell, who is sinister and sleazy and selfishly brutal. Simone, on the other hand, is mostly just tragic.

Copyright © 2021 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © The Criterion Collection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3)

(3)