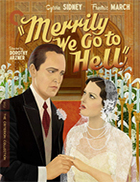

Merrily We Go to Hell

|  As the title should make clear, Dorothy Arzner’s Merrily We Go to Hell is not a romantic comedy, although it is often labeled as such, perhaps because it is focused on a marriage and was directed by the only female director to work consistently during Hollywood’s classical studio era. Sylvia Sidney and Fredric March play the troubled couple, who meet at a penthouse party in the film’s opening sequence. Sidney’s Joan Prentice is a sweet and naïve heiress who catches the eye of March’s Jerry Corbett, an alcoholic newspaperman. He is so soused when they meet that he forgets who she is by the end of the evening, but he still manages to show up at her house for afternoon tea the next day—several hours late. This does not make much of an impression on Joan’s stern, disapproving father (George Irving), but Joan is still smitten, and they end up tying the knot when Jerry proves his love by turning down her father’s attempt to buy him off. All seems well—almost too good—early in the marriage, as Jerry is so happy that he gives up drinking. With his newfound focus and clarity he is able to write a play that gets picked up by a Broadway producer and becomes a big hit, giving Jerry the outright success that had so long eluded him. Unfortunately, the play also brings back into his orbit Claire Hemstead (Adrianne Allen), who is not just his ex-girlfriend, but the ex-girlfriend who broke his heart, drove him to alcoholism, and for whom he still carries a torch. With Claire back in his life, Jerry falls back into drinking and soon he is openly flirting with her and clearly carrying on an affair, which wounds the idealistic Joan deeply—so deeply, in fact, that she decides to engage in her own affair (with a young Cary Grant, no less), thus situating the film firmly in the “pre-Code” subgenre of adulterous melodramas that dramatized the dangers of “modern” concepts like open marriages. It doesn’t take much to guess that Joan doesn’t have it in her to carry on like this for long, and the last legs of the narrative find her and Jerry going their separate ways with the lingering question being whether they can repair the damage and come back together. The answer to that question arrives so abruptly that you might be forgiven for thinking that a reel was lost, but it works in its own way. The film was based on Cleo Lucas’s 1930 novel I, Jerry, Take Thee, Joan, which won the Doubleday, Doran College Humor Campus Prize Contest for 1930 and was originally serialized in College Humor. Lucas wrote it when she was a student at the University of Alabama, from which she graduated in 1929, but apparently never published another novel, although she did publish some short stories and wrote the teleplay for a 1953 episode of Revlon Theatre about a murderous husband who is haunted by the ghost of the wife he killed in a jealous rage. Merrily We Go to Hell is very much a part of the “pre-Code era,” when studios openly violated the tenets of the recently adopted Production Code, which was intended to restrict the depictions of illicit on-screen behavior and ensure a consistency of moral storytelling (the motivation behind this was purely economic, as movies were not protected Constitutional speech at that time and could therefore be legally censored). Because there was no enforcement mechanism—that is, nothing happened to the studios if they violated the Code—it was too tempting for them to heat up the screen, especially since such risqué material was often box office gold. Merrily We Go to Hell is full of such transgressions, starting with the title, which derives from a toast that Jerry likes to give when he is on one of his benders. It is purposefully inflammatory and salacious like many pre-Code movie titles (e.g., 1930’s What Men Want, 1931’s Leftover Ladies, 1932’s Cock of the Air, 1932’s Devil and the Deep), and apparently caused some newspapers to refuse to run ads (while the film was in production it was known by either the I, Jerry, Take Thee, Joan or simply Jerry and Joan). And, even though the film depicts wild parties, excessive drinking, and repeated violations of the marriage oath, it is, like many such pre-Code films, ultimately conservative and redemptive in that it shows that such behavior is fundamentally destructive and must be rejected. Jerry’s excessive drinking is both the symptom of his inability to get over Claire and the cause of his boorish and selfish behavior. However, the film has a problem in that we get very little sense of who Jerry is outside of his bad behavior, which makes Joan’s head-over-heels infatuation with him and willingness to endure his marital transgressions hard to swallow. At some point you can’t help actively rooting for her to leave him and feeling reluctant to cheer their potentially getting back together. Of course, that could very well be the point, as Dorothy Arzner’s films were rarely straightforward Hollywood fare and always bore the marks of her unique perspective. As a female director working in the 1930s and ’40s (she was the first woman to join the Director’s Guild of America in 1936), Arzner was a genuine anomaly. She directed 17 films between 1927 and 1943 and also added to cinema technology by innovating the boom mic (this is why here early sound films are so much more fluid and aesthetic engaging than other films of their era). And, even though her unique place as a female director working in an otherwise entirely male-dominated field is arguably her defining characteristic as an artist, it should be noted that she downplayed her gender and sought to work as any other director in Hollywood. Yet, she couldn’t help but bring her feminine perspective to her projects, and it is hard not to see that in Merrily We Go to Hell, which clearly privileges Joan’s perspective, particularly in her constant disappointments with Jerry’s selfishness and myopia. Sylvia Sidney, who had only recently moved from Broadway to movies, gives a beautifully nuanced performance, and even if her character doesn’t always make sense, she conveys a profound sense of pain when she’s hurt. At the same time, Arzner doesn’t shortchange Jerry, even as he engages in traditionally loutish masculine behaviors. March, who had been nominated for an Oscar two years before for The Royal Family of Broadway (1930) and would win one with his other film of 1932, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, has an insouciant charm. However, the character works as well as it does because Arzner makes it clear that his struggles are borne out of his own emotional pain, which is perhaps why we are able to swallow the film’s otherwise rushed conclusion.

Copyright © 2021 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © The Criterion Collection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3)

(3)