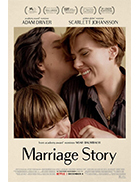

Marriage Story

|  Much like Noah Baumbach’s breakthrough fourth feature The Squid and the Whale (2005), his most recent film, Marriage Story, overcomes a lot of obstacles inherent in its potentially navel-gazing material through brutal honesty and moments of bracing humor. As I wrote about the previous film several years ago, “I have long been resistant to movies about overly self-absorbed characters wallowing in their own self-imposed problems, which unfortunately tends to be a staple narrative device in indie and art film circles.” And, just as I was surprised to find how much I liked that film, I was equally surprised by how much I liked Marriage Story, although it is not quite as good or challenging because its perspective is more limited. The earlier film was inspired largely by Baumbach’s parents’ divorce, and he structured it around the experiences of the parents as filtered through their two children. Marriage Story, on the other hand, was inspired by Baumbach’s own divorce (from actress Jennifer Jason Leigh), so it is told exclusively through the perspective of the parents. This isn’t a bad thing per se, as it keeps the film more tightly focused, but it also takes away the breadth of how divorce’s shocks and aftershocks affect so many in its wake. The story begins with Charlie and Nicole Barber (Adam Driver and Scarlett Johansson) already separated, although Baumbach cleverly disguises this through a touching opening montage in which we see the characters in moments of happiness and connectedness and banal everydayness while the other one narrates what they love about them. With intimate handheld camerawork that feel like the stuff of home movies and is in complete opposition to the rest of the film’s rigid aesthetic, these opening moments paint a quick and accessible portrait of the characters, which is then revealed to be a mediator’s tactic to help them open up in session, which Nicole roundly rejects. Thus, we are jarred from closeness to brokenness, intimacy to distance in rapid succession. From there, the film depicts a largely downward spiral as Charlie and Nicole navigate what becomes an increasingly complicated divorce. They have one child, an 8-year-old boy named Henry (Azhy Robertson), and they both agree (off-screen) that they want the divorce to be as painless as possible and done without lawyers. However, it soon becomes obvious that their post-marriage desires are completely incompatible. Charlie, who is a rising avant-garde theatre director, wants to stay in New York where the couple has lived almost exclusively since they were married, while Nicole, who is an actress and the lead in Charlie’s theatre company, wants to return to her native Los Angeles where she has been cast in the lead role in a new television series. Also, her widowed mother, Sandra (Julie Hagerty), a former television actress herself, and her old sister Cassie (Merritt Wever), live in the L.A. area. Charlie has a love of New York and a distaste for Los Angeles not seen since Woody Allen’s Annie Hall (1977), and he refuses to leave the Big Apple. Nicole, meanwhile, establishes a presence in L.A. by moving in with her mother and putting Henry in a school there. Things get really nasty when Nicole, at the behest of one her show’s producers, hires a high-price attorney, Nora Fanshaw (Laura Dern). This forces Charlie to do the same, although his limited finances mean that he cannot afford the mercenary he first hires (Ray Liotta) and instead must settle for a lawyer in his twilight years (Alan Alda) whose heart is in the right place, but doesn’t have the spit and fire to match someone like Nora. For Baumbach, a big part of the film’s drive is the portrait of marriage not just being torn apart through divorce, but the ugly process of the divorce itself, in which the former spouses unleash their lawyers on each other, unable to even look at the other while their lives are being divvied up in an escalating war of attrition. To Baumbach’s credit, he ably moves us back and forth between empathizing with Nicole and empathizing with Charlie, both of whom are simultaneously right and wrong, fair and unfair, decent and selfish. At times it seems like Nicole is being unfair and unreasonable; after all, it is incredibly convenient for her to set up in L.A. where she has family while Charlie is forced to fly back and forth at great expense and has no family of his own to fall back on. However, as the film unfolds, we gradually learn that Charlie has been a deeply selfish husband who has rarely considered Nicole’s desires in shaping their life together and that their New York existence has largely been for his convenience. While most people will remember the film’s emotional high point being the fierce shouting match into which they devolve in a late scene in Charlie’s meager L.A. apartment, I was more moved by the small moments, the little pangs of agony the characters feel as they realize that what they had is gone and they’ll never be the same again. Baumbach finds a particularly compelling visual for this when Charlie is helping Nicole close her driveway gate and they each steal a glance at each other just as the gate slides closed. An obvious point of comparison, and one that Baumbach invites with both the film’s title and its aesthetic, is Ingmar Bergman’s masterful Scenes From a Marriage (1973) (in one fleeting shot, we see a framed article about Charlie and Nicole that bears that title as a headline). Bergman’s film was broader and more ambitious, even though it was originally shot for television, and the emotional textures he surveyed and broke open are the stuff of truly painful cinema. Baumbach approximates it well, but never quite achieves Bergman’s mastery of interior drama. Baumbach also leavens the heaviness with moments of humor, some of which work better than others (Wallace Shawn, playing one of Charlie’s theatre troupe, bluntly encouraging him to have as much sex as he can during the divorce just feels lazy and crass, but the sequence in which Charlie and Henry are observed by an awkward court-appointed inspector is the stuff of great awkward comedy). In the end, Marriage Story is driven primarily by the power of Driver and Johansson’s performances, both of which are superb, especially in the less dramatic moments when Baumbach gives them extended close-ups that truly reveal their conflicted inner selves. They both rage and wail and scream at various points, but we feel the pain most acutely when they’re alone (or think they’re alone) and any reason to wear a mask falls away. Copyright © 2020 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Netflix |

Overall Rating:

(3)

(3)