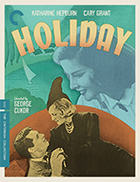

Holiday

|  George Cukor’s Holiday was the third of Cary Grant and Katherine Hepburn’s four screen collaborations between 1935 and 1940. Their previous film, Howard Hawks’s fantastically hilarious screwball farce Bringing Up Baby (1938), had opened just a few months prior, and while Holiday is likewise a romantic comedy, it is a decidedly different kind of film. Based on the 1928 stageplay by Philip Barry, it had already been adapted to the screen in 1930 by director Edward H. Griffith with Ann Harding, Mary Astor, and Robert Ames. Hepburn was the driving force behind the remake, as she had recently bought out her contract at RKO (where Bringing Up Baby was her last film) and convinced Harry Cohn at Columbia that it would make a good project. Cohn was able to put together an impressive package that included Cukor (who had previously directed Hepburn’s Oscar-winning performance in 1933’s Little Women), Grant, and screenwriters Donald Ogden Stewart (who would win an Oscar two years later for adapting another Barry play, The Philadelphia Story, also starring Hepburn and Grant) and Sidney Buchman (Mr. Smith Goes to Washington). In other words, you would be hard-pressed to put together a better roster of classical Hollywood talent in front of and behind the camera, and it shows in Holiday, which is a consistently delightful and entertaining comedy of manners that takes as it primary goal the skewering of the American tendency to amass obscene amounts of wealth for its own sake. As we are currently in an era that is witness to the greatest gap between the rich and the poor since just before the collapse of the stock market in 1929 (not incidentally, the time when Barry wrote his play), there is something terribly current about Holiday’s depiction of the über-wealthy’s obsession with money and status as the only criteria that matter in judging a person’s character and their complete dissociation from anyone not in their rarefied class. The film finds its most compelling visual metaphor in the massive Manhattan home of the fiction Seton family, which resembles both a museum and a mausoleum and acts primarily as an absurdist marble-coated retreat from the rest of the world. When Grant’s character, an up-and-coming businessman named Johnny Case whose primary desire is to quickly make money so he can then take a “holiday” and find himself, first steps foot inside its hallowed walls, he says he is “overcome” by it, which reminds us that such spaces are designed not to be livable, per se, but to be impressive—monuments to wealth accumulated, the very definition of conspicuous consumption. Johnny is in the Seton home because he has recently become engaged to Julia Seton (Doris Nolan), the younger daughter of the family patriarch, Edward Seton (Henry Kolker). Johnny met Julia while skiing in Lake Placid, and until he arrives at her family’s palatial digs, he had no idea that she was so incredibly wealthy and came from such a notable family. And, while Johnny has the potential for great monetary success, his interest is decidedly more philosophical and humane—he wants to live, not just accumulate (as he puts it, “It’s been my idea to make a few thousands early in the game and then quit for as long as it lasts and try to find out who I am and what goes on now, while I’m young and feel good all the time”). His zest for life and unconventional approach to the American dream is reinforced by the fact that his best friends (and unofficial surrogate parents) are an oddball philosophy professor (Edward Everett Horton, who played the same role in the 1930 film version) and his wife (Jean Dixon). Johnny is introduced to Julia’s siblings: her comically morose, alcoholic brother Ned (Lew Ayres) and her unconventional older sister Linda (Katharine Hepburn). Linda has worked to carve out her own space within the monotonous wealth of her family, which is represented by the warm and cozy room she maintains upstairs, which used to be her and her siblings’ playroom. It is an actual living space, rather than an edifice of wealth, and it is not surprising that the characters continually return there for the most important dramatic moments. Of course, anyone can see right away that Linda is a much better match for Johnny than Julia, who continually insists that he reorder his priorities and change his ways to better align with those of her father, who demands nothing less. Linda, on the other hand, respects and admires Johnny’s refusal to tow the line (or at least his reluctance to), and rightly sees him as a much needed counterbalance to her family’s otherwise slanted priorities, which leave little room for the kinds of fun and physicality that both Linda and Johnny love (one scene finds them exchanging somersaults, and in another sequence Grant humorously rides a large tricycle around the house). In short, she sees in him a soulmate, and it takes the entire movie for him to figure that out and for the plot mechanics to maneuver them to that point. In that sense, Holiday is not as strong a film as some of the other Hepburn-Grant collaborations, although it certainly has its charms and its moments of great humor. Cukor clearly relishes staging the comedy, and he lets his stars do their thing as best they can (Doris Nolan, whose career gravitated to television in the early 1950s, has the rather thankless job of playing the love interest you want to go away). Holiday features one of Hepburn’s finest and most memorable performances; it is so iconic, in fact, that film scholar James Naremore devoted an entire chapter to it in his book Acting in the Cinema, where he wrote, “Holiday seems particularly well-suited to Hepburn’s bravura style, not only because it contains a number of gently comic and even ‘screwball’ scenes, but also because it subtly valorizes the art of acting.” Indeed.

Copyright © 2020 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © The Criterion Collection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3.5)

(3.5)