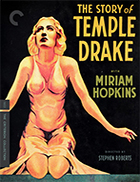

The Story of Temple Drake

|  “How did they ever make a movie of Lolita?” asked the provocative tagline for Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 film adaptation of Vladimir Nabokov’s novel. It was a question that was on everyone’s mind at the time, and it struck right at the divide between what authors could write on the page and what directors could show on the screen. Nabokov had dramatically more freedom to incite, outrage, and scandalize American mores with a satirical novel about a pedophile than Kubrick had in doing the same thing on celluloid—thus, how could it even be done? Jump back three decades, and the exact same question could have been asked (and certainly was asked) of The Story of Temple Drake, except the tagline would have read “How did they ever make a movie of Sanctuary?” Sanctuary was the title of a scandalous 1931 novel by literary giant William Faulkner, who, having failed to garner significant commercial attention with his previous novels, focused his efforts on writing an outrageous Southern potboiler that couldn’t be ignored. The gambit worked, as Sanctuary, with its steamy story about a wild Mississippi debutante named Temple Drake who falls in with vicious bootleggers and winds up the victim of rape and forced prostitution, became a must-read sensation. While the book’s literary value, embodied in Faulkner’s skillful writing, adept use of symbolism, and poetic evocation, was indisputable, all anyone wanted to talk about was the scene in which Temple is raped with a corn cob. Thus, there was little surprise that any attempt to adapt the novel to the silver screen would have … issues. Three years before the film was made, the Hollywood motion picture industry had adopted the Production Code, a carefully written document that outlined what could and could not be depicted in studio films. In some instances, this meant eliminating certain subjects entirely, while in others it meant controlling how those subjects were depicted. So, according to the Production Code, miscegenation was “forbidden,” whereas rape “should never be more than suggested, and only when essential for the plot” and adultery and illicit sex “must not be explicitly treated or justified or presented attractively.” Faulkner’s novel was a veritable laundry list of topics that were either forbidden or had to be carefully circumscribed, which was, of course, the point. One need only look at the various advertisements for the film—“All the Drakes had a wild streak!,” “I can never face the world again!,” “Women whispered her name—Men laughed—but remembered!”—to recognize that Paramount was angling to draw as much attention as possible to the story’s more salacious aspects (although they were forbidden from mentioning the title of Faulkner’s novel anywhere on page or screen). Unfortunately, this has earned The Story of Temple Drake a particularly notorious place in early Hollywood film history, a reputation that grew over the years when the film was pulled from circulation after the Production Code Administration began enforcing the Code with great vigor and persistence under the leadership of Joseph Breen and films like Temple Drake were banned from re-release (it was less than a decade ago that the film was widely seen for the first time since Franklin Roosevelt was President). The problem is that The Story of Temple Drake is actually quite a good film apart from its scandalous reputation, which tends to overshadow any of its other accomplishments. Most notably, it features a powerful central performance by Miriam Hopkins, who was nearing the height of her mid-1930s stardom; impressive cinematography by Karl Struss, who won the first Best Cinematography Oscar for F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise (1927); and sure-handed direction by Stephen Roberts, a Paramount contract director who had helmed nearly 100 short films between 1923 and 1931 before shifting to features in 1932 with the stunt pilot drama Sky Bride, the boxing drama Lady and Gent, and the mystery-thriller The Night of June 13 (one imagines his career would have gone on much longer had he not died of a heart attack in 1936 at the age of 40). The screenplay by Oliver H.P. Garrett, who the previous year had adapted Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms (1932) starring Gary Cooper and Helen Hayes and would later co-write Manhattan Melodrama (1934) and King Vidor’s Duel in the Sun (1946), follows Faulkner’s novel fairly closely, although much of what was made explicit on paper is toned down or thinly veiled on screen. Hopkins plays the eponymous Temple Drake, a free-spirited Mississippi ingenue who lives with her wealthy grandfather, Judge Drake (Guy Standing). Stephen Benbow (William Gargan), an earnest young attorney, wants to marry Temple, but she feels like she is no good and instead leaves a party with one of her many feckless, drunken admirers, Toddy Gowan (William Collier Jr.), who promptly wrecks his car in the middle of nowhere. He and Temple take refuge in a dilapidated Southern mansion owned by Lee Goodwin (Irving Pichel) and his surly wife, Ruby (Florence Eldridge), where they run a speakeasy frequented by a gang of ruthless bootleggers headed by Trigger (Jack La Rue). It is Trigger who rapes Temple and, after he murders another young bootlegger, hauls her off to a brothel in Memphis. Temple eventually kills Trigger and returns home, where she attempts to hide what has happened to her (the original title of the film was going to be The Shame of Temple Drake). Unfortunately, one of the young bootleggers is accused of the murder committed by Trigger, and only Temple’s testimony can clear him, which will require her standing in front of everyone she knows and admitting to all that has happened to her, which she is, of course, reluctant to do. One of the more fascinating aspects of The Story of Temple Drake is how it contrasts the rarefied world of the Southern social elite and the dark, underground world of bootleggers and criminals. Just as Faulkner’s novel did, the film finds visual connections between the two otherwise distinct worlds, notably the presence of large Southern mansions. In Temple’s world of privilege and wealth, the mansions are bright and open, whereas the decrepit manor in which Lee runs his speakeasy is its dark inverse, full of overwhelming shadows, decay, and despair. Karl Struss’s cinematography on films like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931) and The Island of Lost Souls (1932) informs his work here, as he treats the sequences in the Mississippi backwoods as an excursion into the horror genre; it is as if a horror film suddenly invaded a social drama, which makes the looming rape scene all the more horrific. Struss doesn’t verge into pure expressionism, but the film’s middle section is aesthetically isolated in such a way that it feels like a nightmare, albeit one that is all too real for Temple. No one would likely argue that Temple Drake is a feminist film, but it goes a long way toward rectifying some of the less defensible aspects of Faulkner’s novel, particularly the idea that Temple eventually comes to enjoy her sexual debasement. The film makes it clear that Trigger’s raping her is an act of violation so profound that it puts her into an almost catatonic state, and her forced prostitution is not something of pleasure and vice, but rather a further victimization from which she must violently free herself. Her reluctance to take the stand and tell her story is not a blot on her honor, but rather an indication of the double standards by which male and female sexuality are judged and the narrow-minded, patriarchal nature of small-town Southern culture. Temple is seen by the men around her as a “tease” because she maintains control of her own body (she is introduced late one night fending off her date’s increasingly aggressive advances), and there is a temptation to read the film as a case of her finally getting her comeuppance. Some misguided minds have surely understood it as such, but there is little within the film to support such a reading, since director Stephen Roberts works hard to encourage us to empathize with Temple, giving her tear-streaked face numerous close-ups as she struggles with hiding her own shame at the expense of another’s life. Hopkins’s portrayal of Temple, one of the many challenging, unconventional female roles she played in her short career, insists that we understand her as a victim who ultimately stands up for what is right by speaking her own victimhood into the face of those who would rather lock her away than deal with the reality of their culture (a major change from Faulkner’s novel). In this regard, Stephen Benbow is a particularly progressive male hero, one who rejects the simplistic patriarchal assumptions of the men around him and instead insists on fighting for those who lack power and social standing; he is an underdog fighting for other underdogs. His admonition at the end of the film that Judge Drake should be proud of Temple, rather than ashamed, speaks volumes about the film’s sympathetic perspective on her plight, both in her past and what she will surely face after the credits roll.

Copyright © 2019 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © The Criterion Collection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3.5)

(3.5)