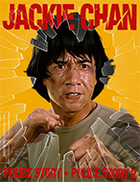

Police Story (Ging chaat goo si)

|  Like Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969), Jackie Chan’s Police Story (Ging chaat goo si) begins and ends with enormous action sequences. Both films seemingly put everything out front in the opening sequence, which sets up the false expectation that any subsequent action couldn’t possibly be as spectacular. Yet, both films explode that expectation with climactic action sequences that improbably top what came before. Of course, that is pretty much all Police Story has in common with The Wild Bunch, as the latter is a deadly serious demystifying western that set a new bar for graphic violence in mainstream cinema, while the former is a goofy action comedy that redefined the boundaries of the martial arts film by incorporating kung-fu theatrics into a modern police procedural. Police Story’s opening action setpiece is set in and around a hillside shantytown outside of Hong Kong where police officers are gathering to nab a notorious crime lord. The cover for their sting operation is blown, and it turns into a massive gunfight that culminates with a car barreling down the hill through numerous buildings as explosions go off left and right (if this sounds familiar, Michael Bay lifted it wholesale for 2003’s Bad Boys II). It’s a huge setpiece that establishes the film’s commitment to grounding its elaborate action in a realistic environment, which Chan employs throughout the film by using and abusing living rooms, parking lots, and, in the film’s spectacular climax, a multi-level shopping mall. Chan, who also produced, directed, and co-wrote the script with longtime collaborator Edward Tang, stars as Chan Ka-Kui, a Hong Kong police detective who, true to genre form, is a bit of a renegade who likes to do things his own way and often takes matters into his own hands, much to the consternation of his superior, Supt. Raymond Li (Kwok-Hung Lam), and his well-meaning uncle, Inspector Bill Wong (Bill Tung). The plot revolves around a drug-smuggling operation overseen by a crime lord named Chu Tao (Yuen Chor), but it serves little purpose beyond providing something on which Chan can string together a series of comic episodes, some of which are pure slapstick (he is hit in the face with a cake not once, not twice, but three times) and some of which are pure, high-octane action. Ka-Kui is put in charge of guarding Chu Tao’s secretary, Selina Fong (Brigitte Lin), who will serve as an important witness in the case against the crime lord, but she is reluctant to be guarded, which leads Ka-Kui to stage a faux attack to “prove” his mettle as a protector that goes amusingly wrong. A running subplot involves Chan’s strained relationship with his endearing girlfriend May (Maggie Cheung), who is constantly being sidelined by his dedication to his policing. By the time Police Story went into production, Chan was not just an enormous star in Asia (particularly China and Japan), but a literal industry unto himself. Having started as a background player in dozens of interchangeable kung fu films in the early 1970s following a childhood stint in the Peking Opera (where he learned much of the acrobatic physicality that he married with kung fu moves to produce his signature brand of action), he broke out as a star in his own right in Drunken Master (Zui quan, 1978), which is often considered the first true kung fu comedy (the year before he had starred in Half a Loaf of Kung Fu [Yi zhao ban shi chuang jiang hu], which was an outright spoof of the genre). Chan tried several times to break into the much desired American market: first with the Hong Kong-produced The Big Brawl (aka Battle Creek Brawl, 1980), then with bit parts in Hal Needham’s The Cannonball Run (1981) and Cannonball Run II (1984), where he picked up the idea of including outtakes and bloopers and footage of blown stunts during the closing credits. A few years later Chan starred in The Protector (1985), a gritty Hollywood-produced action vehicle set in Hong Kong that misused him in a role that was better suited to Chuck Norris or Clint Eastwood and, as a result, failed to connect with anyone. Part of Chan’s impetus to make Police Story was his miserable experience making The Protector, and he exerted his control over every aspect of the production, especially the fight choreography which he tailored to both his unique skillset as a martial artist and his comically likeable on-screen persona. The control that Chan exerted over the production paid off handsomely, as Police Story set a new standard for contemporary Hong Kong action films. There was nothing in it that was particularly new, but Chan elevated the various elements through both intensification and reformation, putting various pieces together in ways that other filmmakers had not. For example, throughout the early ’80s there had been numerous popular police thrillers that incorporated martial arts, but Police Story was the first to be both a full-fledged police thriller and a full-fledged kung fu movie. And, of course, it is also very much a comedy, with moments of pure slapstick that borrows variably from the Three Stooges, Buster Keaton, and Charlie Chaplin. Chan’s style of fight choreography is more balletic than anything, relying heavily on speed, dexterity, and crack precision of movement that turns the melees into comical art that often leaves you laughing and gasping at the same time. Chan’s greatest gift is his innovative use of props in the fight scenes, and part of the pleasure is watching him turn otherwise banal objects like ladders and benches and clothing racks into essential elements of both attack and defense. Like Fred Astaire, Chan knew that realism was essential to the effect and the “wow” factor, and much of the action unfolds in long shots and long takes that make it clear that Chan and his dedicated team of stuntmen are doing everything for real. No editing, or gimmicky camera angles, or quick inserts—real stunts, often wildly dangerous, unfolding in real time and space. Of course, not everyone was appreciative of Chan’s innovation and artistry—to wit, Vincent Canby of The New York Times, who dismissively said that the film’s “principle interest [is] as a souvenir of another culture.” Granted, there are elements of Police Story that are clunky and some of the humor is so obvious that it doesn’t quite work. Yet, the impressiveness of the stunts and the exhilaration of the action and the genuine sense of love that Chan puts into it all smooths out the wrinkles and covers over the holes, leaving us with a glorious sense of wild abandon.

Copyright © 2019 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © The Criterion Collection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3)

(3)