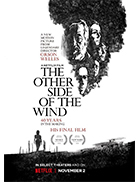

The Other Side of the Wind

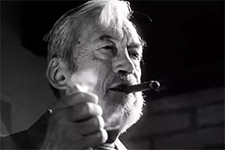

|  Orson Welles liked to say that, when he was a young artist making his name in New York and then in Hollywood, he was competing with all the other young, would-be artists. However, in his later years, he was no longer competing with other young artists, but rather with his younger self. As the man whose feature film debut was Citizen Kane (1941), Welles spent the rest of his life and career battling against the perception that he had left everything on the table his first time at bat and could never match, much less exceed, that grand, crowning achievement. Kane was a blessing in that it definitively proved that Welles was the towering cinematic artist he was expected to be after having already conquered both Broadway and radio by the time he was 25, yet it was also a curse because it hung around his neck for decades, the achievement by which everything else he did—with far fewer resources and support—was judged. In 1970, when he was 55 years old, Welles launched a new project that he hoped would rekindle his Hollywood career, which had been dormant since Charlton Heston convinced Universal to hire him to direct Touch of Evil (1958). He spent the next dozen years working on various independent film and television projects in Europe, a number of which were completed—The Trial (1962), Chimes at Midnight (1966), The Immortal Story (1968)—and a number of which remained unfinished—The Deep (shot between 1966 and 1969) and his infamous Don Quixote, which he worked on sporadically starting in 1955 until his death in 1985. That new project Welles launched in 1970, The Other Side of the Wind, has for nearly four decades been another of Welles’s legendary unfinished works—a lost film languishing in some film vault somewhere, tied up in legal limbo and interpersonal squabbling and unlikely to ever see the light of day. Rumors abounded over the years as various Welles collaborators—director Peter Bogdanovich, producer Frank Marshall, and film scholar Joseph McBride, all of whom worked on the film—struggled to raise money, untangle the myriad legal issues (the film was a co-production among U.S., French, and Iranian investors), and track down the existing elements to complete the film. There was talk that it simply couldn’t be completed, that too much was missing, that what Welles had shot was a mess. There was also talk that the film was very nearly complete, that Welles had put together something approximating a final cut that would require only minimal work. As it turned out, the truth lay somewhere in the middle, and after decades of fruitless wrangling, The Other Side of the Wind has finally been rescued from the pit of lost films, completed by a small army of filmmakers and technical artists using modern technology so that we can experience the rough majesty of one of the great filmmakers’ final works. Starting with 45 minutes of footage edited by Welles himself, the film was completed using his notes, annotated script, and nearly 100 hours of footage by Oscar-winning editor Bob Murawski (The Hurt Locker), with a newly commissioned scored by three-time-Oscar-winning French composer Michel Legrand, who began his career working with French New Wave visionaries like Jean-Luc Godard and Agnes Varda and had previously worked with Welles on his documentary F for Fake (1973). The result is something very close to a genuine revelation, a film of grand ambition that reflects both the turbulence of Hollywood in the early 1970s, as the old guard was giving way to the new, and the eternal struggle of artistic evolution. There is a tendency to think of the film as Welles’s bid to “keep up” with the new waves that had been breaking all around the cinematic world throughout the 1960s, including in Hollywood. Some have seen it as a project designed to prove that the old man still had it and could match discontinuous editing, disjointed narrative, meta-commentary, and explicit content with the best of the younger generation, especially since a major component of the film’s plot revolves around precisely that dynamic. But, to view The Other Side of the Wind as an effort by a titan of the classical era to adapt himself to the changing guard is to ignore the entirety of Welles’s career up until that point, which was defined largely by experimentation. Welles was never a conventional artist whether on stage, on air, or on screen, and he was always challenging the status quo, pushing artistic boundaries, and thumbing his nose at how others thought he should do it. There’s a reason why he was never able to settle into a Hollywood career, why he spent most of his life in exile, forging a new path of independence that would be emulated by later actor-filmmakers like John Cassavettes. Citizen Kane, lest we forget, was an experimental film that challenged virtually everything about the classical Hollywood style and dared to make a mockery of William Randolph Hearst, one of the most powerful men in the world. Welles only made Kane when his original idea, an adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness told entirely from the protagonist’s first-person perspective, never got the traction it needed. The script for The Other Side of the Wind describes it as “a film within a film, a film about a film, a film about a film-maker.” The story unfolds over the course of a day and night, with the central event being a 70th birthday party for Jake Hannaford (John Huston), a once-powerful Hollywood director who is attempting to launch a daring comeback film. Hannaford, who bears traces of towering film directors like John Ford, Howard Hawks, and, yes, both Orson Welles and Huston himself, was specifically modeled on Ernest Hemingway’s mix of macho genius and self-destruction. He is a gruff, out-of-place auteur surrounded by both sycophants and critics, including a shrill film writer named Juliette Riche (Susan Strasberg), a bookish film historian named Marvin Pister (Joseph McBride), and a former child actor named Billy Boyle (Norman Foster). One of Welles’s true strokes of genius was to depict Hannaford’s party through dozens of lenses, as members of the press swarm the party, shooting everything on whirling 16mm and Super 8mm cameras. The party thus takes on a hectic, jumbled vibe of movement, energy, tension, and conflict, with shots constantly shifting celluloid formats and perspectives. It appears chaotic, but it is actually deftly choreographed, interweaving and balancing various interpersonal conflicts as the night unfolds. One of the central tensions lies in the relationship between Jake and Brooks Otterlake (Peter Bogdanovich), a much younger film director who idolized and followed Jake before becoming hugely successful and surpassing him. Jake, meanwhile, is obsessed with John Dale (Robert Random), the leading man of the film he is completing, thus fully revealing the homosexuality desire he has hidden his entire life with his penchant for stealing his actors’ girlfriends and wives. Which brings us to the film-within-the-film, which is a striking evocation of European art-film nonsense. Shot in gorgeous 35mm color, it features an inexplicable, wordless relationship between Random’s character, a young hippie biker, and a woman played by Oja Kodar, Welles’s lover and co-writer of the screenplay. Much of the action takes place on a deserted back lot, and both actors spend significant portions of the film naked. It is shot through with an intense eroticism that culminates in a sexual encounter in the backseat of a moving car that is as vivid and compelling as anything Welles ever did while also bringing in an air of sensuality and carnality that had been absent from his previous works. Welles, who was an outspoken critic of the esoteric films of Michelangelo Antonioni (which he found “boring”), appears to be satirizing the pretensions of European art cinema, with their taboo breaking and abstract symbolism, but the visual qualities of the film-within-the-film are so striking, so vivid, so captivating on their own terms that they almost beg to be taken seriously even as we recognize their essential ludicrousness (at one point a studio boss named Max David is brought in to watch the footage in the hopes of securing “end money,” and all he can do is complain about it). Welles, more than anyone, knew the limits of the studio system. It will forever remain one of the great tragedies of film history that Welles spent so many years struggling to complete projects and never again had access to the full financial and technological resources that made Citizen Kane possible. We have long since moved past the myth that Welles’s career was a downward trajectory of failed potential, as his independent films are all striking works of art that probably no other filmmaker could have managed. Yet, it is still true that Welles left behind a long trail of incomplete works that remind us of the struggles he endured to maintain his independence. Near the end of his 1989 book The Magic of Orson Welles, film scholar James Naremore writes that “[Welles’s] reputation will always depend to some degree on fragments and traces. Like Coleridge’s unfinished poem ‘Kubla Khan,’ his life’s work denies us scholarly closure; a romantic artifact, its oneiric quality is heightened by a sense of unfulfilled possibility.” With the completion and wide distribution of The Other Side of the Wind, some of that possibility has now been fulfilled. Copyright © 2018 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Netflix |

Overall Rating:

(3.5)

(3.5)