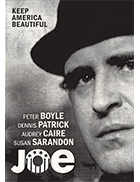

Joe

|  One of the defining critical essays about American cinema in the 1970s is Robin Wood’s “The Incoherent Text: Narrative in the ’70s,” which was originally published in Movie in 1980–81 and later republished in a slightly revised version as a chapter in his book Hollywood From Vietnam to Reagan (1986). In this essay, Wood argues that there is a richness of experience to be had in films that are functionally and ideologically incoherent, by which he meant “films that don’t wish to be, or to appear, incoherent but are so nonetheless, works in which the drive toward ordering experience has been visibly defeated.” Wood writes of films in which “incoherence is no longer hidden and esoteric: the films seem to crack open before our eyes.” And, while Wood mentions a number of films in the essay, with the majority of his attention being focused on Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976), Richard Brooks’s Looking for Mr. Goodbar (1977), and William Friedkin’s Cruising (1980), there is a film whose lack of mention has long surprised me: John G. Avildsen’s Joe, which is, in every way, a perfect example of “the incoherent text.” Like the films Wood examines in his essay, Joe is a film whose “interest lie[s] partly in [its] incoherence … [it] achieve[s] a certain level of distinction, [has] a discernible intelligence (or intelligences) at work in [it] and … exhibit[s] a high degree of involvement on the part of [its] makers.” It also fits temporally, as the incoherent texts about which Wood writes were products of Hollywood in the 1970s, a period that Wood describes as one of “generalized crisis in ideological confidence”: “Society appeared to be in a state of advanced disintegration, yet there was no serious possibility of the emergence of a coherent and comprehensive alternative,” a “quandary … [that] can be felt to underlie most of the important American films of the late 60s and 70s.” What makes Joe such a fascinating and frustrating cinematic experience is the way it is such a mishmash of incongruities, confusion, and cynicism, all qualities that Wood ascribes to incoherent texts. The story takes place over several days in New York City and focuses on the unlikely relationship that develops between two middle-age men: Joe Curran (Peter Boyle), a bitter tool-and-dye maker, and Bill Compton (Dennis Patrick), a wealthy advertising executive. While they have nothing in common economically, socially, or personally, they share a deep resentment toward hippie youth culture and the radical shifts in American culture that were contributing to the “generalized crisis” of which Wood wrote. Joe wears his anger loudly and proudly on his sleeve; when we first meet him, he is sitting at a bar ranting and raving about “niggers,” “fags,” and “hippies,” grousing about his perceived disenfranchisement and an unfair system that coddles the lazy and refuses to celebrate honest workers like himself. Bill, on the other hand, keeps his anger and resentment tightly coiled beneath his three-piece suits, although he can’t keep it contained when he confronts Frank Russo (Patrick McDermott), the would-be artist-cumdrug dealer who is currently living with Melissa (Susan Sarandon), his 20-year-old daughter. Frank knows how to push Bill’s buttons, and he does so with such effectiveness when Bill goes to their apartment to retrieve Melissa’s belongings after she is hospitalized for overdosing on amphetamines that he sends Bill into a rage that results in Frank’s death. Sitting at the bar next to Joe, a man he has never met and with whom he has almost nothing in common, Bill lets slip that he killed Frank, a revelation that Joe celebrates. He immediately wants to be friends with Bill because he sees in him a fellow angry traveler on the confused cultural highway, albeit one who benefits from the system in ways that Joe never can. Bill humors Joe by meeting him at his favorite bowling alley, going out for drinks, and even taking his prim socialite wife, Joan (Audrey Caire), to dinner at the crowded Queens apartment where Joe lives with his browbeaten, simple-minded wife, Mary Lou (K Callan). There is always the suggestion that Bill is just trying to stay on Joe’s good side out of concern that Joe might turn him in, but the film also wants us to believe that these two men find genuine common ground and forge a real connection, one that feeds off their collective anger about the way the world is turning. Of course, that anger, at least to some extent, derives from jealousy, as they see the younger generation taking advantage of life in a way that their generation was not allowed, and when they have the opportunity late in the film to participate in an orgy with a group of hippies, their hesitation is minimal at best. They see the youth generation as cultural rot, but rot they want a part of, but can’t really have. At its best, Joe captures with raw, direct power the intensity of cultural animosity—one might say loathing—that was gripping the nation at the time, and in some ways it was prophetic; it was made just before the Kent State shooting and the subsequent Hard Hat Riot in New York City, both events that Joe Curran would have heartily endorsed. At the time of the film’s release, virtually everyone associated with it was an unknown on the cusp of breaking through. Director John G. Avildsen had helmed a handful of soft-core sexploitation films, and after Joe he directed Jack Lemmon to an Oscar in Paper Tiger (1973) and then won one himself for Rocky (1976). Joe was the first produced script by Norman Wexler, who would go on to write the gritty (and much more coherent) ’70s classics Serpico (1973) and Saturday Night Fever (1977). The script is a fascinating mess that merges zeitgeist-defining cultural awareness with a streak of vigilantism that is at times critical and at other times dangerously regressive. It’s hard to get a read on what the film’s ideological positioning is, which is compounded by Wexler’s choice of a contrived scenario as the backbone for its confused message(s) about the violence of the generation gap (one wonders how it was nominated for an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay, unless they were simply voting for its sheer chutzpah). Peter Boyle, on the other hand, who had labored as an actor for nearly a decade in bit roles and commercials, had a major breakthrough in the title role, embodying the embittered Joe with a unique mix of angry bluster, foolish naivete, and dangerously coiled rage. He is simulatenousyl pathetic and scary, yet there is something imminently likeable about him, even as he blurts out his racist, sexist, homophobic, and generally misanthropic view of the world. At least Joe is honest, which is more than can be said for Bill, who is a generally loathsome character unevenly played by Dennis Patrick. Patrick had two decades of acting credits already under his belt, mostly in television series, but his performance is woefully stilted and unconvincing; virtually everything he does feels forced and unnatural, which is quite the opposite of Boyle’s Joe, who feels like a fully wrought force of nature. It’s no wonder that their relationship, which is already contrived on a narrative level, feels so awkward and mostly unconvincing. Yet—yet—despite all its various failures, Joe is an incredibly intriguing film that is hard to shake once you’ve seen it. It falls right in line with Robin Wood’s assertion that incoherent films fascinate not in spite of, but because of, their ideological confusion. In an interview with The New York Times, Boyle expressed his dismay that audiences seemed to misread the film and cheer Joe’s violence (he contended that the film was a clear anti-violence cry against U.S. involvement in Vietnam). Joe itself offers no real answers for anything, as it can be read different ways depending on which part you’re watching. It seems to condemn Joe’s regressive social attitudes and love of violence, yet the objects of his derision are largely deserving, as most of the hippies portrayed in the film are criminals and frauds who betray any sense of progressive values or morality (it is clearly a post-Manson hippie world). Joe, with his kitschy “Honor America” sticker, extensive gun collection, and reactionary admiration of Richard Nixon could very well be a product of today’s Trumpian political chaos, which makes Joe not just a fascinating bit of cinematic and political history, but a reminder that the sense of anger, disenfranchisement, and panic engendered by social and political change is a threat to which we keep returning.

Copyright © 2018 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Olive Films / MGM | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(2.5)

(2.5)