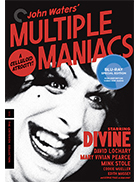

Multiple Maniacs

|  What to say about John Waters’s underground cult classic Multiple Maniacs, a home-made celluloid bomb inspired equally by Ingmar Bergman, Kenneth Anger, Andy Warhol, and Herschell Gordon Lewis? What can you say about a film that climaxes with the protagonist, a homicidal maniac played by a 300-pound drag queen, in a room filled with half a dozen dead bodies, most of whom she has stabbed to death and one of whom she has partially cannibalized, being raped by a giant lobster? What can you say about a film that opens with a self-proclaimed “Cavalcade of Perversions” that includes such ridiculously grotesque sights as a “puke eater” and a fetishist who gets off on sniffing a bicycle seat? What can you say about a film that not only introduces the term “rosary job,” but depicts it in all its graphic glory while intercutting the blasphemous sexual deed with a re-enactment of the life of Christ that includes the miracle of the seven loaves and fishes recreated with Wonder Bread and canned cat food and the stations of the cross? Rhetorical questions all, as there is so much to be said about Multiple Maniacs and so little because the film speaks so willfully, aggressively, and perversely for itself. The second of Waters’s feature films (the first being 1969’s slapdash Mondo Trasho) and the first to be made with synchronized sound, it is a compendium of Waters’s various fascinations, obsessions, and—yes—manias. Having been thrown out of film school at New York University for drugs and living back home in Baltimore with his parents, Waters was the quintessential, greasy-haired malcontent who wanted to strike out at everything in the world—conservatives and liberals, straights and hippies, homo and hetero, the devout and the defiled. Many people bear the label “equal opportunity offender,” but Waters truly earns it by going after virtually every category imaginable and treating them with equal levels of disdain, all for his own amusement. And that is, ultimately, what makes Multiple Maniacs, like so many of his other early works, even remotely enjoyable, despite their visual shoddiness and juvenile gross-out sensibilities: They’re made in a spirit of humor and revolt that has no room for anything even remotely resembling pretension. Pretense is just another target to skewer, especially through Waters’s giddily transparent self-recognition of his own trash aesthetic. Waters’s films have been called many disparaging names over the years, although his own ballyhoo descriptions are probably the most apt. He described his early amateur effort Roman Candles (1964) as “a triple projected trash epic,” Mondo Trasho as “a gutter film,” and his most iconic and notorious film, Pink Flamingos (1972), as “an exercise in bad taste.” Thus, it is little surprise that Multiple Maniacs has its own matinee-ready self-applied moniker— “a celluloid atrocity”—although Waters has also referred to it humorously as Rancid Strawberries, a riff on Ingmar Bergman’s Wild Strawberries (1957). The plot of Multiple Maniacs is simultaneously simple and all over the place. The opening sequence introduces us to the protagonist, Lady Divine (Glenn Milstead, a.k.a., Divine, in a hideous Elizabeth Taylor wig), a murderous con artist who runs a deliriously revolting sideshow called “Lady Divine’s Cavalcade of Perversions” with her platinum-haired boyfriend Mr. David (David Lochary). The sideshow is just a ruse to draw in “straights” so that Lady Divine and her gang, which also includes her daughter Cookie (Cookiue Mueller), can rob them and, in some instances, kill them. Unbeknownst to her, Mr. David is having an affair with a ditzy woman named Bonnie (Mary Vivian Pearce), with whom he plots to escape. When Lady Divine finds out, she sets her sights on killing them both, although she is temporarily waylaid when she is seduced in a church by Mink (Mink Stole), who becomes her lover and accomplice. The story really goes off the rails in the final 20 minutes, which include the aforementioned murders, cannibalism, and giant lobster. A final sequence in which Lady Divine, covered in blood (her own and others’), runs down a street terrorizing unsuspecting people and sending them into a panic is a pretty good metonym for Waters’s overall intent. Like all of Waters’s early films, Multiple Maniacs is a distinct product of Dreamland Studios, the small Baltimore production company he founded in his bedroom in the late ’60s, around which assembled a motley group of outsiders, weirdos, and rejects who dubbed themselves “The Dreamlanders.” This group included the actors Divine, Mary Vivian Pearce, David Lochary, Cookie Mueller, and Mink Stole, art-school-drop-out-turned-production designer Vincent Peranio, and actor-turned-casting director Pat Moran. As John Waters described the group while making Multiple Maniacs: “The main characters ... became an extended family, took LSD together and made those movies. We were trying to do what the Manson family did, only with a movie camera.... And you can see the rage, which was very anti-hippie. It was punk before its time. It was that attitude of defiance, which there wasn’t really a lot of then.” The Manson connection was especially meaningful to Waters, and Manson-related themes and props show up repeatedly in his work, perhaps never so much as in Multiple Maniacs, where Sharon Tate’s murder is at first attributed to Lady Divine, but then revealed as a lie at the end (the arrest of Manson and his family happened during the film’s production, so Waters had to change to script at the end). Manson was like a deranged muse to Waters, who has noted the influence openly and proudly: “We wanted to do the same thing as the Manson family,” he once said. “We wanted to scare the world.” The notion of “family” is one that extends throughout Waters’ work; because he lived during the early years with the Dreamlanders in a kind of deviant extended family, the characters in his films tend to exist within a similar environment: the trailer-park family in Pink Flamingos, the group forming Lady Divine’s Cavalcade of Perversions in Multiple Maniacs, and the drape gang in Cry-Baby (1990). The Dreamlanders also set themselves in contrast to other subcultures, most notably hippies and punks, with which they were often confused. Although they may have looked like hippies in the late ’60s, Waters has stressed repeatedly that he and the Dreamlanders deviated severely from hippie culture. In some ways, their relationship to the hippie culture was a paradox because, as Waters one said, “We basically made fun of hippies, but we were hippies.” One of the aspects in which the Dreamlanders deviated most from hippie culture was in their acceptance and celebration of violence. Although Waters claims to have never instigated actual physical violence in his life, violence has always intrigued him, and it is a conspicuous component of his early films (Roman Candles, for example, included a re-enactment of the Kennedy assassination). Thus, it is not surprising that Multiple Maniacs would culminate in copious bloodshed, all of which was filmed in the same sloppy, slapdash manner as Herschell Gordon Lewis, the original purveyor of gore movies. Waters, who manned the camera himself, had a hard time figuring out where to point it in any given shot or how to keep his actors in focus, but he never lost sight, for even a moment, of his ultimate goal, which was to shock the world and crack himself up at the same time. Multiple Maniacs may not be a very good movie, but you can’t help but say at the end, “Mission accomplished.”

Copyright © 2017 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © The Criterion Collection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(2.5)

(2.5)