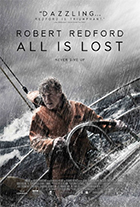

All Is Lost

|  In J.C. Chandor’s All Is Lost, Robert Redford joins a small fraternity of actors who have literally carried an entire movie on their shoulders by playing the only character on-screen. Not even Tom Hanks’s impressive turn as a survivor on an island in Cast Away (2000) counts since his lengthy sojourn as the lone soul on screen is bookended by sequences before and after that feature other characters. Same goes for Danny Boyle’s similarly themed 127 Hours (2010), in which James Franco plays a rock climber who is trapped in a gorge when his hand becomes wedged underneath a boulder. Impressive feats of acting to be sure, but not true one-man shows. In J.C. Chandor’s All Is Lost, Robert Redford joins a small fraternity of actors who have literally carried an entire movie on their shoulders by playing the only character on-screen. Not even Tom Hanks’s impressive turn as a survivor on an island in Cast Away (2000) counts since his lengthy sojourn as the lone soul on screen is bookended by sequences before and after that feature other characters. Same goes for Danny Boyle’s similarly themed 127 Hours (2010), in which James Franco plays a rock climber who is trapped in a gorge when his hand becomes wedged underneath a boulder. Impressive feats of acting to be sure, but not true one-man shows.No, we’re talking about a tiny, tiny group of films that literally feature only a single actor on screen for the entire duration: Yaadein (1964), a little-known Hindi film directed by and starring Sunil Dutt as a man who reexamines his life after he comes home and thinks that his wife has left him; Robert Altman’s adaptation of the one-man play Secret Honor (1984), in which Philip Baker Hall plays Richard Nixon; and, most recently; Rodrigo Cortés’s Buried (2010), which takes place entirely inside a coffin where Ryan Reynolds has been buried alive in the Iraqi desert (but even that doesn’t quite count since we hear numerous off-screen characters via his cell phone). Interestingly, All Is Lost diverges from these other one-actor films by refusing to use dialogue to make up for the lack of bodies on screen. The other films mentioned above are filled with talk, talk, talk, as the lone characters are incessantly verbal (talking mostly to themselves and, by extension, us, except in the case of Buried). All Is Lost, on the other hand, is virtually devoid of the human voice. With the exception of a brief voice-over reading of a vague, apologetic letter that Redford’s unnamed character has written in what he believes to be the final days of his life, he utters only a few words during the film’s 100-minute running time, including a gloriously raging F-bomb that essentially summarizes and unleashes the character’s otherwise unspoken frustrations and anguish. The entirety of All Is Lost takes place on the ocean. We first meet Redford’s character as he is violently awoken when his sailboat runs into a floating cargo container that breaches the hull and sends seawater spilling into the cabin. It is only the first of many, many disastrous turns that he will face over the course of the next eight days at sea, as it becomes increasingly apparent that nature or God or some unseen force wants to ensure his demise. The reasons for his sailing the ocean blue alone are never explained, nor is virtually anything about his personal background. Instead, Chandor (who both wrote and directed) relies on Redford’s inherent star presence and the intensity of his character’s fight to survive against the forces lining up against him to carry the film, a gambit that is largely successful. At 77 years of age, Redford is both aged and impressively virile, going about his work on the boat with a forceful sense of purpose that turns activities like patching holes, mopping up water, and hoisting sails into existential mini-epics of human survival. He speaks little, but the flinty look in his eye and his tense body language tell us virtually all we need to know about what is going on inside his head. Redford conveys a deep sense of loneliness (truly the old man and the sea), yet his instinctual need to fight back against nature and persevere suggests a deeper well of strength that belies his self-imposed isolation. Chandor, whose previous film was, ironically, the incredibly talky, ensemble financial drama Margin Call (2011), has essentially made a grand experiment, trusting in the inherent intrigue of the survival narrative and Redford’s decades-honed screen presence to fill in the gaps left by his outright dismissal of anything resembling a conventional narrative. Redford’s performance, the first in a film he hasn’t directed since An Unfinished Life (2005), is appropriately spare and naturalistic. There is nothing particularly stunning about it, but it has a quiet strength that endows even the most mundane of actions with a sense of life-and-death humanism. Granted, the film does suffer from the almost unavoidable exhaustion that accompanies any story built around disaster after disaster; it starts to take on an almost morbid sadism, and you find yourself wondering what on earth could possibly happen next (Chandor trades the economic violence of Margin Call for something decidedly more physical here). Alas, there is always sometimes waiting around the corner—dwindling supplies, a massive storm, tiny fish pecking away at the underside of a life raft, circling sharks, another massive storm—and if the film maintains our attention, it is simply because we connect with the base desire to survive, which embodied by someone like Robert Redford becomes all the more gripping. Either that, or we simply wonder whether Chandor will have the gumption to engage in the cinematic perversity of allowing a star of Redford’s wattage to die unknown and alone in the middle of oceanic nowhere. Copyright ©2013 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Roadside Attractions |

Overall Rating:

(3)

(3)