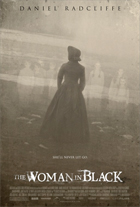

The Woman in Black

|  The Woman in Black is a doggedly old-fashioned Gothic chiller, filled with dank rooms, creepy old toys, flickering candles, and miles of gray mist. There are strange sounds in the night, glimpses of shadowy figures in mirrors and windows, and furniture that moves on its own. The film’s simple, abiding virtue is its resilient belief in the inherent creepiness of these things, and while director James Watkins is not above a few cheap scares that involve things suddenly appearing in the frame accompanied by a resounding crash of instrumentation, he sets his sights primarily on evoking an uncanny sense of dread that makes virtually everything in the frame seem sinister, threatening, or weirdly out of place. The Woman in Black is a doggedly old-fashioned Gothic chiller, filled with dank rooms, creepy old toys, flickering candles, and miles of gray mist. There are strange sounds in the night, glimpses of shadowy figures in mirrors and windows, and furniture that moves on its own. The film’s simple, abiding virtue is its resilient belief in the inherent creepiness of these things, and while director James Watkins is not above a few cheap scares that involve things suddenly appearing in the frame accompanied by a resounding crash of instrumentation, he sets his sights primarily on evoking an uncanny sense of dread that makes virtually everything in the frame seem sinister, threatening, or weirdly out of place.The story takes place in England at the turn of the 20th century, which is a particularly interesting historical moment to set a classical ghost story because the crumbling of older modes of life in the face of modern technology echoes the familiar tug-of-war between spirituality and rationality; the old ways hold on despite the force of social evolution (it is not surprising, in this regard, that Bram Stoker set Dracula, a story to which The Woman in Black owes no small debt, in the then-present tense of 1897, rather than in the past). Thus, we aren’t surprised to find superstition running rampant through an isolated, rural village, but that superstition feels outdated, a thing of the past to be discarded in the age of telephones and automobiles, the latter of which the villagers view with suspicion and even fear. In his first major post-Harry Potter role, Daniel Radcliffe stars as Arthur Kipps, a young, melancholic lawyer who is still struggling emotionally with the death of his wife three years earlier while giving birth to their son. Kipps is assigned by his firm to travel to the small, coastal village of Crythin Gifford to attend to the papers of Alice Drablow, a recently deceased widow. It is immediately clear upon his arrival at that his presence is not welcome (it even seems to strike fear in the villagers), although no one will talk to him or explain why they so desperately want him to get back on the train to London. The only person in the village who isn’t immediately trying to get rid of him is Samuel Daily (Ciaran Hands), a wealthy businessman whose wife (Janet McTeer) is still obsessively mourning the death of their young son. The death of children figures prominently in The Woman in the Black; in fact, the film opens with a chilling sequence in which three little girls playing with their dolls are driven by an unseen force to drop their playthings and calmly jump out the window to their deaths. Despite professing a belief in spirituality, Arthur refuses to heed the villagers’ warnings, partially because his continued employment with the firm requires his successfully completing the job of going through Mrs. Drablow’s papers, which takes him to her dilapidated manor, Eel Marsh House. The manor, which is half-covered in vines and surrounded by rot and decay, is so isolated from the rest of the village that the one road leading to it is flooded every day by a muddy low tide, thus turning it into a literal island surrounded by deathly marshes (the location was probably inspired by Lindisfarne, where Roman Polanski shot Cul-de-Sac). It is there that Arthur first sees the titular woman in black, standing outside the house near a cemetery. That is just the beginning, though, as his days and nights at Eel Marsh are tormented with sights and sounds related to Mrs. Drablow’s anguished family history, one of the great mainstays of gothic literature. As Arthur sifts through her papers, a story begins to unfold involving Mrs. Drablow’s sister, her illegitimate son, and a series of deaths that have the village gripped in fear. The screenplay by Jane Goldman (Kick-Ass, X-Men: First Class) is based on the 1983 novel by Susan Hill, which was previously adapted into a long-running stageplay (it has been playing continuously in London’s West End for 23 years) and a 1989 made-for-television movie that initially ran on Britain’s ITV on Christmas Eve. Goldman makes some substantial changes to the story, particularly the ending, which now seems to be derived from the third act of Sam Raimi’s Drag Me to Hell (2009). Fans of the novel will likely balk, but Goldman clearly understands the mechanisms by which gothic stories work, and she attends to the story with a minimum of fuss, leaving large sections of the film with virtually no dialogue (Radcliffe spends a lot of time walking around tenuously with a candle in his hand). This results in a decided lack of character depth and some clumsy devices to convey relationships (for example, Arthur’s son always drawing him a perpetual sad face), but that’s not really the point. The screenplay simply provides a narrative framework that director James Watkins can fill with the proper atmosphere and punctuate from time to time with goosey scares, which he does admirably. Watkins, whose only previous film is the gritty straight-to-video horror-thriller Eden Lake (2008), reaches deep into his bag of tricks, and even if he doesn’t pull out anything new, he executes the expected with a sense of style and respect for what has worked in the past (he’s not trying to reinvent the wheel, but rather make us appreciate just how functional the wheel is). He is particularly drawn to the “slow reveal” in which a character enters a room (usually hidden behind a closed door), after which we cut to that character’s perspective as he or she slowly—very, very slowly—pans his or her line of sight from one end of the room to the other. This, of course, in no way reflects how actual human beings would behave (if you were looking in a room where you thought something threatening might be hiding, wouldn’t you look around wildly, frantically trying to identify it?), but in cinematic terms it works marvelously, racheting up the tension with each ticking second and turning every object in our visual path into a potential point of surprise. Watkins and his sound designers are also attentive to the importance of the horror film’s aural dimension, giving us sharp distinctions between the cadences of wet stone and hollow wood and at times presenting us with sounds that we think might be one thing, but are later revealed to be something entirely different. As one of the initial productions from the recently resuscitated Hammer Films, which reinvented horror in the 1950s and ’60s with modernized takes on gothic tales starring Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing, The Woman in Black is a particularly welcome throwback, reminding us that old and creepy, when done well, is always good for raising the hairs on the back of your neck. Copyright ©2011 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © CBS Films |

Overall Rating:

(3)

(3)