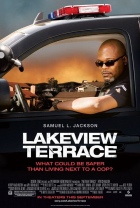

Lakeview Terrace

|  There is an intriguing, racially charged psychodrama buried in Lakeview Terrace, one that is frustratingly difficult to unearth from beneath its many hardened layers of rote villainy and thriller plot mechanics. The story takes place in an established upscale neighborhood in the scenic hills above Los Angeles (not incidentally, the same one where Rodney King was beaten by police officers in 1991), which becomes the new home of Chris and Lisa Mattson (Patrick Wilson and Kerry Washington), an attractive and respectable young married couple. He’s a grocery-store-chain executive with a Berkley degree and a self-consciously liberal agenda and she’s an artist who works from home, but pines for the day that they start a family. All would be well except for the race factor: Chris is white and Lisa is black, which doesn’t sit well with their next-door neighbor, a veteran police officer named Abel Turner (Samuel L. Jackson). There is an intriguing, racially charged psychodrama buried in Lakeview Terrace, one that is frustratingly difficult to unearth from beneath its many hardened layers of rote villainy and thriller plot mechanics. The story takes place in an established upscale neighborhood in the scenic hills above Los Angeles (not incidentally, the same one where Rodney King was beaten by police officers in 1991), which becomes the new home of Chris and Lisa Mattson (Patrick Wilson and Kerry Washington), an attractive and respectable young married couple. He’s a grocery-store-chain executive with a Berkley degree and a self-consciously liberal agenda and she’s an artist who works from home, but pines for the day that they start a family. All would be well except for the race factor: Chris is white and Lisa is black, which doesn’t sit well with their next-door neighbor, a veteran police officer named Abel Turner (Samuel L. Jackson).Because he is played by Jackson, Abel is the clear centerpiece of the movie, a hyperrealized vat of contradictions who is as infuriating as he in intriguing. In essence, Abel is a striking character and a sharp reminder that prejudice cuts not just both ways, but all ways, and is usually rooted in a deep-seated sense of how things “ought to be,” rather than how they are (the very fact that film deals with such touchy issues is really quite extraordinary, given how Hollywood usually avoids racial issues like the plague). Deeply conservative and stoically regimented, Jackson’s widower runs his home like a military operation, keeping his 15-year-old daughter (Regine Nehy) and 11-year-old son (Jaishon Fisher) under tight supervision and constantly eradicating any elements of urban black culture of which he does not approve (primarily, non-standard English and wearing jerseys representing the “wrong” basketball players) while still holding fast to the notion that blacks and whites should be separate. Thus, Abel is immediately suspicious of Chris and Lisa because of their mixed marriage, and his unease is inflamed by a series of small incidents, such as Chris unthinkingly flicking a cigarette butt into his bushes and he and Lisa having a steamy in-the-pool interlude that, unbeknownst to them, is in full few of Abel’s children. Because he is a police officer, Abel immediately cuts an imposing and intimidating figure, and he constantly reduces Chris to sputtering and stumbling with a simple turn of phrase or unbroken stare. The film’s best moments, which drip with the kind of interpersonal friction that are the hallmarks of director Neil LaBute’s best works (In the Company of Men, The Shape of Things), take place in the early stages when Abel passive-aggressively drops hints and clues about his dislike of Chris and Lisa’s union and his desire for them to leave the neighborhood. He never comes out and says it directly, but the venom in his words is unmistakable. And, had the film remained in this terrain, it might have developed into a seething portrait of both neighborly friction and racial tension. Instead, the screenplay by David Loughery and Howard Korder keeps nudging the material into rote thriller territory, with Abel slowly but surely losing any shades of gray and becoming a one-dimensional monster who must naturally be destroyed. In short, it eventually asks us to detest Abel, rather than understand him, and it is at that point that the film falls apart. Unfortunately, LaBute seems to go along with this, even after his more nuanced opening scenes that gave Abel’s extreme tendencies a solid psychological and social foundation (as a child of the ghetto who clawed his way out, he is both bitter toward whites who have their fortunate lives handed to them and angry at blacks who continue to wallow in victimhood). Instead, the films takes on a bland sense of efficiency, which all but steamrolls the intriguing interpersonal dynamic that could have sent people out of the theater talking (the more subtle and interesting elements of Abel’s prejudice take a back seat to a “big revelation” two-thirds of the way through the film that more directly, but less interestingly, explains his revulsion toward Chris and Lisa). The mounting sense of violence primed to explode is externalized via an encroaching wildfire that is first hinted at via news broadcasts, but soon looms over the neighborhood as an ominous cloud and then arrives just in time for the show-down climax to bathe the proceedings in a hellish yellow-red glow. The overt visual symbolism works in its own right and adds to the tension, but by the time the fire arrives the story has dug so deeply into its own rut of predictability that, like the rest of the film, it seems more hackneyed than inspired. It is worth noting that the film ends on the image of a hillside aflame, suggesting that, despite the ideological simplicity of the audience-pleasing conclusion, the spark that set everything in motion is still alive and well, a small, potentially disruptive caveat to the film’s otherwise simplifying nature. Copyright ©2008 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Screen Gems |

Overall Rating:

(2.5)

(2.5)