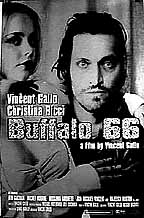

Buffalo '66

| Vincent Gallo's "Buffalo '66" is a haunting, comical nightmare of narcissism, pent-up rage, and maddening loneliness--and, yet, it has a happy ending. It is a film that resists simple description, mostly because it is constructed of so many ill-fitting pieces that it has a kind of insane consistency all its own. "Buffalo '66" presents life--or, at least, the life of its gaunt, oddball protagonist, Billy Brown--as an unfulfilled quest for acceptance and love. The entire film can be summed in one scene, where Billy, in a state of sadness that borders on nausea, asks another character to hold him. When she does, his immediate reaction is to pull back and say, "Don't touch me." The majority of "Buffalo '66" is about how and why he came to be this way, and how he is helped out of it. Co-writer and director Vincent Gallo stars as Billy, a long-limbed, greasy loser who is being released from a five-year jail sentence when the film opens. The opening shots have a stark, despairing quality, as we watch from long shots cut to the sound of lonely piano chords as Billy is released into a gray, wintry nothingness, stands around, sleeps on a bench for a while, and then asks to be let back inside the prison so he can go to the bathroom. He eventually takes the bus back into his hometown of Buffalo, where he plans to be reunited with his parents, who think he is married and has been working for the government for the last five years. In order to keep up this pathetic charade, Billy kidnaps a young woman named Layla (Christina Ricci) from her tap dancing class and cajoles her into posing as his wife. The manner in which he persuades her into doing this favor is almost as bizarre as the fact that Layla has numerous chances to escape, but never does. Billy intimidates her physically, asks her nicely, and threatens not to talk to her anymore unless she does what he says--he's like an overgrown child who mixes the menace of physical violence ("If you make a fool of me, I swear to God I'll kill you right there") with adolescent emotional threats ("If you a good job, well, then, you can be my best friend"). From a narrative point of view, this moment, about twenty minutes into the film, is the point at which the audience is either on for the ride or balking at the sheer lunacy of this vision. It is this scene that will likely determine whether you see "Buffalo '66" as a deranged masterpiece or a rambling piece of repetitive blather. One might try to chalk it up to bad scriptwriting or inept imagination, but don't be too sure. Gallo and co-screenwriter Alison Bagnall have a unique plan in store for the development of their characters, and they successfully maintain this almost otherworldly atmosphere for the duration of the film, suggesting that they are not so much sloppy as they are determined to make this film stand out from the pack. Once Billy and Layla arrive at his parents' house for the big reunion, we begin to understand why Billy is so antisocial, and even begin to feel some sympathy for him. His parents (played with outlandish comic malevolence by Anjelica Huston and Ben Gazzara) are even stranger than he is. Dad is an ex-singer whose paranoia drives him to panic at the table when Billy's knife, which is sitting harmlessly on the table, points in his direction. Mom is a football-crazed loony who hasn't forgiven Billy for being born on a day when the Buffalo Bills, her favorite team, were playing. It's the only game she ever missed, and the Bills lost. These scenes at the Brown household are like a surrealistic sitcom, with the lying ex-con and his false bride sitting at a square table with his deranged parents who are only feigning interest in his return. When Layla asks to see pictures of Billy when he was a child, his mother gets excited and asks the father, "Where the picture of Billy," suggesting that they have only one; and, although she finally finds it, Layla ends up looking at more pictures of Jack Kemp, O.J. Simpson, and the Buffalo Bills' caterer than pictures of Billy. At one point, Layla launches into a long, made-up story about how she and Billy supposedly met, and the whole time Mom is glued to the football game on the TV set in the living room, oblivious to her supposed daughter-in-law while she twitches nervously at the game's proceedings. What's even weirder is the fact that game isn't even live--it's a taped game that she has surely seen before, which makes her anxiety at the game's outcome that much more ludicrous. And that's only the first half of the film. The second half details the rest of the night after Billy and Layla leave his parents' house. At some point (arguably before Billy even kidnaps her, when she overhears him in a telephone conversation with his mother), Layla begins to develop real feelings for Billy, to which he is, for one reason or another, unwilling or incapable of responding. As the film moves forward, we see flashbacks and scenes that further illuminate Billy's personal dilemma. It all comes together in a scene at a Denny's restaurant, where Billy and Layla run into Wendy Balsam (Rosanna Arquette), a girl Billy was in love with at school but could never approach. Instead, he starred at her in class and obsessively walked by her house each day. It's a sick, sad moment when Wendy asks him, "Didn't you used to walk by my house everyday?" and Billy can only push out a weak lie, "I had a friend who lived nearby." It is here more than any other moment that we see how lonely Billy's life has been; how he has been incapable of getting in touch with another human being, and how shamed he feels because of it. Perhaps it started with his parents, who are shown in flashbacks mistreating and ignoring him. The only place Billy seems to feel comfortable is in the local bowling alley run by the kindly Sonny (Jan-Michael Vincent), and his closest friend is a slightly retarded boy called Goon (Kevin Corrigan). For most of the film, Billy is a truly loathsome character--foul-mouthed, rude, unfeeling, even cruel--but our anger at his actions are slowly shifted from him to the roots of his problems. And, we even begin to see why Layla feels for him, despite the bitter manner in which he treats her. "Buffalo '66" is certainly an original film, one that can truly be labeled a vision of its particular artist. It is crammed with visuals--Gallo and cinematographer Lance Acord make use of every corner of the screen, often using screens within the main screen to show flashbacks. Some of it seems a bit much at first, and if anything Gallo might be accused of overkill. The film's imagery has the washed out, faded quality of old color photographs that have been lying in the sun. The colors are dark and muted and not quite there; but, amidst all this dimness, there are sometimes scenes of sudden dazzling light that don't so much make the frames feel brighter, as they give the feeling of simply being overexposed. Gallo has worked as an actor for some of the most well-known independent directors of the last decade, from Abel Ferrara ("The Funeral") to Bille August ("The House of Spirits"), and it is obvious that he was paying attention during filming. Gallo has left a unique imprint on every facet of this film, especially his cutting, often risky direction that is both abstract and notable for its narrative fluency, alternating between discreet long shots and tight close-ups. But there is also his striking performance in the lead role and even the music, which he composed. The fact the parts of the film are semi-autobiographical in nature makes it that much more his own. Christina Ricci matches him every step of the way in perhaps her best role as the almost inexplicably compassionate Layla. As a director, Gallo realizes this and frames one of the most important conversations between Billy and Layla with the static camera looking only at her, allowing the audience to watch her responses to his every word. Ricci, with her doll-like round face, pouting mouth, and huge eyes, gets more mileage out of one hurt glance than many actresses get out of Oscar-winning speeches. Dressed in a tiny blue dress that looks about two sizes too small, matching stockings, and glittery tap shoes, she holds every frame she's in simply because she is both fascinating and utterly frustrating at the same time. We never learn anything about her past, but the bored look on her face in the tap dancing class suggests that, prior to being kidnapped by Billy, her life was dull and without meaning. Perhaps it is in trying to save Billy from his unrelieved inwardness that she finally finds meaning in her life while simultaneously giving him, for the first time, something to live for. Copyright ©1999 James Kendrick |

Overall Rating:

(3.5)

(3.5)