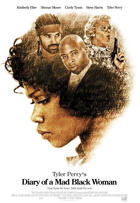

Diary of a Mad Black Woman

|  The majority of critics who have given bad reviews to Diary of a Mad Black Woman -- and there are a lot of them -- have focused on what they see as a chaotic disjuncture between the film’s drama and its comedy. In this view, the drama is of the straight, melodramatic, romantic tearjerker sort, whereas the comedy, embodied primarily in big grandmamma Madea, played in drag by the film’s producer/writer Tyler Perry, is ridiculous and outsized. It’s as if two (or more) movies collided and their respective parts randomly intermixed. The majority of critics who have given bad reviews to Diary of a Mad Black Woman -- and there are a lot of them -- have focused on what they see as a chaotic disjuncture between the film’s drama and its comedy. In this view, the drama is of the straight, melodramatic, romantic tearjerker sort, whereas the comedy, embodied primarily in big grandmamma Madea, played in drag by the film’s producer/writer Tyler Perry, is ridiculous and outsized. It’s as if two (or more) movies collided and their respective parts randomly intermixed.I agree that the comedy in Diary of a Mad Black Woman is deliriously over-the-top; it’s crude, crass, and often hilarious. However, what I don’t see is the drama as being so straightforward. In fact, in its own way, the film’s dramatic components are just as outrageous as its comedic moments -- that is, they’re very “theatrical.” Thus, the film’s tonal ruptures are not as severe as some have made them out to be. Consider the story: Kimberly Elise plays Helen, the dedicated and loving wife of 18 years to Charles (Steve Harris), a successful Atlanta attorney. However, he’s not just successful; he’s SUCCESSFUL. They live in an enormous, isolated mansion, the kind you usually associate with media moguls, movie stars, and royalty. Their marriage has been slowly coming apart over the years, likely in conjunction with Charles’ rising economic success, and early in the film he unceremoniously dumps Helen. Well, unceremoniously is a rather chaste word to describe what he does to her. Not only has Charles got himself a new woman, a thinner, saucier, (and lighter) piece of arm candy with whom he has already had two children on the sly, but he hired a mover to pack Helen’s things and moves the new woman into the house before announcing his intention to end the marriage. When he finally does get around to leveling the crushing blow, Helen resists, and Charles forcibly throws her out of the house. Because Helen signed a prenup, she has no claim to any of the money. She has no job, no skills, and nowhere to go. Now, at a base level, there is a foundation of truth to this scenario. Men can be pigs, women can delude themselves into thinking everything is alright when it’s not. Marriages sometimes go bad, and people who once professed to love each other can end up treating each other like poisoned enemies. The subtext of genuine tragedy is what holds up Diary of a Black Woman’s emotional punch, but in no way is the dramatic narrative, as envisioned by Tyler Perry, anything short of sensationalistic. Everything is cranked up a few notches, which is the film’s reigning narrative principle. Helen winds up living with her grandmother, Madea, a recurrent character in Tyler Perry’s stageplays. Madea is large and in charge, a resilient, gun-toting, no-nonsense woman who barrels through life like a bull in a china shop, doing anything she can to protect those she loves and wreaking havoc on those who dare get in her way. Madea is a theatrical conceit through and through; like the film’s drama and comedy, there is a kernel of truth to her character -- there are people like Madea in the world, as fans of Perry’s work will readily testify -- but as incarnated on-screen in amusingly bad drag by Perry himself, Madea is an exaggeration. More to the point, she is a fantasy character, a sort of unleashed id who does what repressed characters like Helen only wish they could do. At one point, Helen and Madea return to the house Helen shared with Charles, and Madea coerces her into some anger-releasing destruction in the new woman’s closet. Okay, that’s within the realm of the possible. However, when Madea produces a chainsaw from out of nowhere and begins to shred the house entirely, the film slips into a wicked-funny fantasy world. The crux of Diary of a Mad Black Woman concerns Helen’s healing process, as she goes from a destroyed trophy wife to self-sufficient woman. She slowly allows herself to become involved with Orlando (Shemar Moore), who was the young man Charles hired to pack up the U-Haul with Helen’s things. At first, Orlando bears the brunt of Helen’s understandable anger, as he is a convenient stand-in for all men who have hurt women. The only problem is, she got the wrong stand-in. Not only is Orlando gorgeous in the way only Calvin Klein models are, but he’s thoroughly and fundamentally decent -- a true nice guy. Once again, we see the film embracing exaggeration, as Orlando is a picture of male perfection in every sense. The only mark he might have against him is the fact that he’s not rich, but the film has already made the point of money being a deeply corrupting influence. The final third of the film introduces a tragic, soap-opera-esque narrative turn that forces Helen back into Charles’ world. This development plays as both payback for all the cruelty Charles has shown her and also a chance for his redemption. If the film has a substantial flaw, it occurs in the last five minutes, as Helen makes a decision for one man over another and does it with a kind of blasé cruelty of her own that is highly questionable. Of course, taken within the context of a film that embraces sensation at every turn, it’s not that surprising. While Tyler Perry’s work is largely unknown to white America (admittedly including this member of that segment), he has a large and dedicated fanbase among African Americans. He has successfully staged seven Urban Theater productions in the past six years, several of which have been filmed and sold as straight-to-DVD releases (both prominently feature Madea). His work has a constancy to it, particularly his bold mixing of comedy and drama to get at painful emotional truths, though it’s not for all tastes. One of Perry’s strongest skills is his ability to infuse spirituality into his stories without coming across as awkward and didactic. Perry is a Christian artist, which is evident in Diary of a Mad Black Woman; however, he never force-fits religion into the story, but rather uses his characters’ Christian values to help define them. Of course, some won’t see it that way, but those who accuse the film of bashing you over the head with Christianity tend to see any inclusion of religion into a film as propaganda. The film’s explicit Christianity is not fashionable to the intelligentsia, who consider it conformity at best, ignorance at worst, but it hardly makes the film disingenuous, a wildly inaccurate accusation leveled by those who simply disagree with its worldview. In short, those who dismiss Diary of a Mad Black Woman see only its exaggerated surface and forced narrative conceits. However, if you can enjoy it on the surface level, but also connect with the primal emotions boiling beneath (as almost anyone who has been spurned by a spouse or lover should be able to do), you will see Perry’s work for what it is: genuine emotional truth and spirituality heavily packaged in a commercialized vehicle of a thousand different stripes. Copyright ©2005 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright ©2005 Lions Gate Films |

Overall Rating:

(3)

(3)