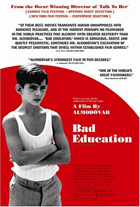

Bad Education (La mala educación)

|  In Bad Education (La mala educación), Pedro Almodóvar’s deeply saturated noir/melodrama pastiche, past and present, fiction, and truth are so intertwined and turned around that any sense of mystery the film develops is ultimately subsumed by its incessant obsession with unknowability. In typical Almodóvar fashion, it is simultaneously a serious mystery/drama and a campy near-parody, turning its source genres inside out, but staying true to their emotional pull. In Bad Education (La mala educación), Pedro Almodóvar’s deeply saturated noir/melodrama pastiche, past and present, fiction, and truth are so intertwined and turned around that any sense of mystery the film develops is ultimately subsumed by its incessant obsession with unknowability. In typical Almodóvar fashion, it is simultaneously a serious mystery/drama and a campy near-parody, turning its source genres inside out, but staying true to their emotional pull.The film’s opening credits sequence -- by far the film’s best feature -- riffs on Saul Bass’s edgy credit design for Hitchcock’s Psycho by tearing away successive layers of imagery to reveal the credits while Bernard Hermann-esque music pounds on the soundtrack. The peeling away of layers to reveal only more layers is the film’s primary visual and thematic trope; at one point, Almodóvar uses a wonderful transition device by zooming in on a shred of movie poster pasted on a wall that is nearly buried among dozens of other layers of torn posters and having it morph into the full one-sheet 16 years in the past. The multiple layers of characterization and memory serve to remind us that answering questions in Almodóvar’s funny-perverse alternate cinematic universe only brings up more questions. Gael García Bernal stars as a struggling young actor named Ignacio, but who calls himself Ángel (his “stage name”). One day, he walks into the office of movie director Enrique Goded (Fele Martínez), who was his first adolescent love in Catholic boarding school 16 years earlier, and presents him with a semi-autobiographic story titled “The Visit” about the abuses they endured there. In doing so, Ángel instigates a web of flashbacks, both genuine and fictionalized, the intertwining of which is so thorough that the film calls into question the very notion of memory. Is anything we remember really “truth,” or is to too fundamentally altered by the filters of time and perception? Essentially, the film tells Ángel and Enrique’s story at three different times in their lives: when they were 10-year-old Catholic schoolboys in Franco Spain in the late 1960s, when they were young adults finding themselves in the late 1970s, and then finally when they reunite in the early 1980s. Yet, some of the flashbacks that we think are the real deal turn out to be not entirely genuine, and we get revised versions later on, not to mention a film-within-the-film variation that may be completely fictionalized or may have a ring of truth to it. Ever since his international breakthrough in the late 1980s, Almodóvar has been considered one of the cinema’s most notable provocateurs, and in Bad Education he doesn’t disappoint. He gives us drag queens, explicit sex, drug use, and a few doses of wicked black comedy -- and that’s just in the first 15 minutes. The film’s overt gayness is something of a return to form for Almodóvar, who has been making essentially straight films for the last decade and a half. The fact that Bad Education is not about homosexuality (rather, it simply features a majority of characters who are gay) makes that return all the more intriguing and effective in that it doesn’t waste energy calling attention to itself. If there is any real controversy in Bad Education, it is the narrative centrality of a Catholic priest (Daniel Giménez Cacho) who sexually abused Ángel as a child and Ángel’s subsequent vengeance. Coming on the heels of numerous widely publicized cases involving pedophilic Catholic priests, the film resonates alarmingly with recent headlines. It doesn’t seem that Almodóvar is making any particular statement about the clergy sexually abusing the children in their care; rather, these disgusting incidents have become so routine that they’re simply fodder for the plot. Some may see this as a missed opportunity, but it’s such an obvious and broad target that it takes more gumption for Almodóvar not to make a grand statement about it. Yet, there is something potentially problematic about the sexuality in Bad Education. The fact that Ángel discovers his homosexuality at the same time he’s being abused by a priest would seem to suggest a connection between the two, surely something Almodóvar doesn’t intend. On a separate, but related note, Almodóvar’s depiction of budding childhood sexuality is, to put it lightly, way off course, as he depicts two 10-year-old boys discovering each other in a movie theater in a scene that is “tastefully” filmed, but still plays more like a perverse pedophilic fantasy than the poignant moment of emotional revelation it should be. While Almodóvar otherwise nimbly plays the lines between fantasy and reality, melodrama and camp throughout Bad Education, this is a glaring moment in which it all becomes terribly confused. Almodóvar and cinematographer José Luis Alcaine (who also shot Almodóvar’s 1990 film Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!) mix the styles of film noir and late-’60s Spanish melodramas (one of which plays a crucial role in the story) to achieve a strange, lurid visual stylization that is particularly effective in the ’Scope aspect ratio. The visuals give the film’s provocative subject matter just the right amount of punch; the film stays grounded, but there’s always a slippery subtext of meta-cinematic glee pushing at the seams. Like the trannies that are so central to the story, Bad Education seems to constantly be playing dress-up, but with a purposeful lack of convincingness that allows us to always see what’s just beneath if we’re looking for it. Copyright ©2005 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright ©2004 Sony Pictures Classics |

Overall Rating:

(3)

(3)