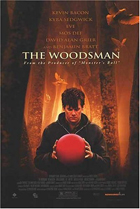

The Woodsman

|  From the very beginning, movies have frequently aligned the audience with criminal heroes. There is a sense of subversive excitement in sinking into the darkness of a movie theater and identifying with characters who break rules, laws, and sometimes bodies. The sexy couples in outlaw movies from Bonnie and Clyde (1967) to True Romance (1993), the crime lords and mafia dons that range from the psychotic (Scarface, 1931) to the grandiloquent (The Godfather, 1972), even serial killers like Hannibal Lecter and Norman Bates -- all have been elevated to a kind of mythic status on the silver screen. It’s pleasurable to stand in their presence because it allows us to step outside the ordinary, if only for a few hours and only in our minds. From the very beginning, movies have frequently aligned the audience with criminal heroes. There is a sense of subversive excitement in sinking into the darkness of a movie theater and identifying with characters who break rules, laws, and sometimes bodies. The sexy couples in outlaw movies from Bonnie and Clyde (1967) to True Romance (1993), the crime lords and mafia dons that range from the psychotic (Scarface, 1931) to the grandiloquent (The Godfather, 1972), even serial killers like Hannibal Lecter and Norman Bates -- all have been elevated to a kind of mythic status on the silver screen. It’s pleasurable to stand in their presence because it allows us to step outside the ordinary, if only for a few hours and only in our minds.Thus, it is always a genuine shock when a film features a criminal protagonist who complicates our innate desires to identify with him. In The Woodsman, Kevin Bacon plays such a character, a convicted child molester named Walter who has just been released from prison after 12 years. In our culture, pedophiles, even more so than murderers, are the closest thing we have to true pariah -- Others with a capital “O.” It’s not hard to find a person, however distinguished and respectable on the outside, who won’t cop to a fantasy of hurting or killing someone he really despises, but virtually no one will admit to having sexual desires toward children, much less acting on them. It’s beyond the pale -- unforgivable because it’s unimaginable. In The Woodsman, we are asked to see life through Walter’s tormented eyes as he not only readjusts to life on the outside, but also attempts to come to terms with the unacceptable inner desires that 12 years of imprisonment have not curbed. Bacon gives a toweringly effective performance, one that conveys a man who is truly haunted and at war with himself. He is at turns pathetic, frustrating, and charming. At one point he says quietly to another character, “I’m not a monster,” something he fully believes. Yet, what he doesn’t understand is that monstrosity is in the eye of the beholder. His interpretation of “hurting” a child is not the same as everyone else’s, and that conflict between his sexual desires and his desire to be “normal” -- something he professes in his therapy sessions -- is tearing him apart inside. The film’s suspense lies in waiting for his resolve to crack, which may bring with it things we don’t want to see. Bacon anchors the film with his deeply humane, but never sentimental performance, which is crucial because the narrative and first-timer Nicole Kassell’s direction sometimes threaten to overwhelm its quiet sincerity. Most egregious is a badly played scene in which Walter narrates in his head a faux sports play-by-play as he watches another potential molester stalking a schoolyard; it’s hard to imagine what the filmmakers were trying to convey here. Most of the story deals with the everyday aspects of Walter’s new life, which involves living in a small apartment in the bleak landscape of urban Philadelphia across the street from a schoolyard (a somewhat implausible plot point, but one that nicely illustrates in a visual sense Walter’s inability to escape his temptations). He soon becomes involved in a burgeoning relationship with Vickie (Kyra Sedgwick), a woman with whom he works at a lumber yard. Vickie is tough-as-nails on the exterior, but it’s just a façade for her inner warmth. She, too, nurses spiritual bruises, so it’s no small wonder that she and Walter understand each other. While their relationship works on an emotional level, it, like much of the film, is saddled with too much overt symbolism. Vickie, despite her hardened look and the battered old truck she drives, lives in an apartment overflowing with plants, marking her as a nurturer who will help ease Walter’s reintegration into society (their moment of true connection is when she brings him a cutting from one of her ivies). The color red is also given heavy symbolic importance, in both a red rubber ball that shows up in several fantasy sequences to represent Walter’s temptation and in the coat of a 12-year-old girl (Hannah Pilkes) who may be his undoing. The color also connects her to the story of Little Red Riding Hood, which is referenced by the police officer assigned to Walter’s case (Mos Def, in an understated and riveting performance). Walter’s role is that of both woodsman and wolf -- savior and monster to himself and others battling it out in the same exhausted body. This symbolic flourishes function mainly to take some of the edge off the precarious, disturbing subject matter. By adding an element of the fantastical, if only in a metaphorical sense, screenwriters Nicole Kassell and Steven Fechter (who also wrote the play on which the film is based) are able to suggest a heritage of emotional damage stretching back through the ages. It’s a way of forgiving Walter without denying the impact of his crimes. The Woodsman never offers any explanation for Walter’s behavior; he isn’t held up as a victim of abuse or neglect, which helps mitigate any tendency to offer excuses or pass the blame off on someone else. Nevertheless, the film clearly wants us to see him as more of a victim than a monster; in fact, he’s a victim of his own monstrosity. Although no blame is laid for his behavior, Walter’s urges are presented as somehow innate and therefore unavoidable. All he can do is cope with them, which in and of itself victimizes him. His is also clearly positioned as being in society’s crosshairs, particularly at work where a nosy receptionist (Eve) finds out about his past and tries to passively-aggressively get him to move on someplace else. Even the drab, grainy mise-en-scène of Philadelphia’s gray landscape creates an oppressive force against Walter and his attempts to do “right.” On the surface, this would seem to stack the deck unfairly, but The Woodsman still manages to suggest moral ambiguity, which ultimately allows the viewer to make up his or her own mind. Walter may have done terrible things and may do them again, but we are never allowed to lose sight of the fact that he is a human being, just as his victims are. If he for once came across as anything less than human, it would be too easy to vilify and reject him. If The Woodsman is at all disturbing, it is not because it simply deals with a pedophile, but because it works so hard to humanize one. Copyright ©2005 James Kendrick All images copyright ©2005 Newmarket Films |

Overall Rating:

(3)

(3)