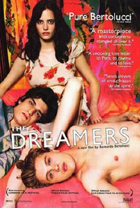

The Dreamers

|  At one point in Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers, a rock is thrown through a window, disrupting an attempted suicide. It’s a moment of bold, if somewhat cheap symbolism, illustrating how the revolution raging in the streets just outside literally crashes in on the lives of the film’s three young protagonists, thus forcing them to finally make a real decision about where they stand. At one point in Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers, a rock is thrown through a window, disrupting an attempted suicide. It’s a moment of bold, if somewhat cheap symbolism, illustrating how the revolution raging in the streets just outside literally crashes in on the lives of the film’s three young protagonists, thus forcing them to finally make a real decision about where they stand.The Dreamers takes place in Paris in 1968, a time of great social turmoil that was instigated by the government’s firing of the much revered Henri Langlois, the founder of the Cinémathèque Française. Soon, the streets were filled with protestors, barricades were constructed, and police in riot gear were chasing insurgents waving communist flags. It was the very epitome of the 1960s, that virtually mythical era in which real change was a genuine possibility and everything that had been taken for granted as rock solid was sudden fluid and in flux. Norms, taboos, politics, the cinema—all were suddenly up for grabs, and Bertolucci’s film aims to capture that tumult in all its audacious glory. Unfortunately, The Dreamers only sporadically evokes with any real power the time in which it is set. All the period detail is there, right down the heavy use of Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix on the soundtrack. However, that period detail takes a backseat to the film’s story, which concerns the relationship between a blank young American student named Matthew (Michael Pitt) and a pair of incestuous French twins, the fiery Isabelle (Eva Green) and the brooding Theo (Louis Garrel). This triumvirate of attractive, sexually adventurous youth is meant to represent, I suppose, a generation on the brink, but they come across mostly as callow and self-absorbed. Their increasingly outré sexual hijinks should be a political statement, but their insulation from the world outside renders them just kinky and silly—a bunch of kids experiments for the first time and deluding themselves into depths of feeling that aren’t really there. One of the film’s primary themes is the distance between appearances and reality, particularly in relation to the three central characters. This is first hinted at when Matthew meets Isabelle and she appears to have chained herself to the gates of the Cinémathèque Française in protest. This impresses him duly, but it turns out that the chains are a farce, which is an apt description of the young protagonists’ political posturing. They talk a good talk, fervently quoting the directors and critics of Cahiers du Cinéma, but they never take it to the streets. Instead, they remain insulated within the walls of the Isabelle and Theo’s parents’ expansive apartment, engaging in a series of games that mix sex and movie trivia. The zero-sum nature of their game is visually realized in the increasingly disgusting condition of the apartment, by the end cluttered with piles of garbage and filth with the threesome holed up together in a makeshift tent rendered from Isabelle and Theo’s childhood. Bertolucci, best known as the director of such truly groundbreaking films as The Conformist (1970) and Last Tango in Paris (1972), stages the sexual shenanigans with a frankness and honesty that is refreshing, although he sometimes tends to slip into an arty pretentiousness, such as the scene when Matthew takes Isabelle on the kitchen floor while Theo causally fries some eggs. It’s the kind of scene that would have made a statement 35 years ago, but here plays like an unintended parody of New Wave dislocation. The film’s greatest flaw, though, may be that Bertolucci indulges too much in the great sin of nostalgia, thus reducing the film’s political firepower by washing it in a hazy wave of “Remember when …” This is especially true of the film’s attitude toward the protagonists’ love of the cinema. They speak heatedly of Nicholas Ray, Chaplin and Keaton, and others, and Bertolucci juxtaposes their actions with scenes from crucial films from the 1930s and 1960s (some would argue the two greatest decades in the cinema), but the irony is that their passion for film makes them seem more shallow than anything. Granted, 1968 was a time in which filmmaking could really, truly, be a revolutionary act, but Bertolucci and his protagonists fails to connect the politics of the cinema with the politics of the street in a meaningful sense; only those who lived through the period and have their own memories of it will find any real connection. To be fair, Bertolucci achieves some moments of great power, particularly at the end when Matthew, Isabella, and Theo finally join the crowds in the blazing streets and each has to make his or her own decision, but perhaps this is only because it comes as such a respite from the previous two hours of their silly self-indulgence. Copyright ©2004 James Kendrick All images copyright ©2004 Fox Searchlight Pictures |

Overall Rating:

(2)

(2)