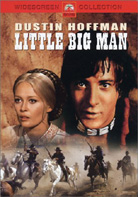

Little Big Man

| Few directors have become so absolutely central to the American cinema and then obsolete with the speed and intensity of Arthur Penn. Like other important directors of the 1960s, including Sam Peckinpah and John Frankenheimer, Penn got his start in television and became a name as a film director by tapping into the zeitgeist in such a way that shockwaves were sent throughout the entertainment industry and the culture at large. Penn’s revelatory moment was 1967’s Bonnie and Clyde, a violent, funny, thumb-your-nose-at-authority ode to outlaw glamour and the repressiveness of modern society. It perfectly encapsulated all of Penn’s most important themes, namely the social outsider who challenges social hegemony and, more often than not, loses. Thus, it isn’t hard to see why he was drawn to the big-screen adaptation of Thomas Berger’s revisionist comic Western novel Little Big Man. The story is told in flashback by a 121-year-old curmudgeon named Jack Crabb (Dustin Hoffman, encased in thoroughly convincing old-age prosthetics by make-up wizard Dick Smith), who claims to be the sole white survivor of the Battle at Little Big Horn, better known as “Custer’s Last Stand.” Jack’s story is a lengthy narrative that has the often-outrageous tone of a tall tale—one wonders whether the events of his extraordinary life are legendary in the sense that they are constructed, not retold. Myth-breaking was one of Penn’s specialties; his best films, including Bonnie and Clyde, Alice’s Restaurant (1969), and Night Moves (1975), all exposed and dismantled various mythological constructions passed down and reinforced by cinematic narratives, whether that be the moral authority of the police to gun down gangsters or the all-knowing confidence of the hard-boiled detective. Like those films, Little Big Man is best described as an anti-myth, as it takes all the ideological power of that great American myth, the Western, and takes it apart bit by bit. At times comedic and other times brutally violent, Little Big Man is a tonal collage, mixing slapstick humor and pathos with such wild abandon that one can’t be blamed for wondering if it were directed by 10 different people. But, this was part of the film’s strategy, to keep the audience off-kilter, always wondering not only what will happen next, but the tenor of its presentation. Jack’s life is dominated by his constant shifting between the worlds of Cheyenne Indians and white settlers. This, in and of itself, makes him the perfect Penn protagonist, because he is the perennial outsider, neither fully white nor fully Cheyenne, always on the fringes. After his family is killed by a war party, 10-year-old Jack is taken in by a kind chief named Old Lodge Skins (Chief Dan George) and raised as a Cheyenne, who refer to themselves as “human beings.” During an ill-fated battle with the cavalry, Jack uses his whiteness to save his own skin (not the last time he will do this) and is returned to the world of “civilization.” There he is taken under the wing of a fundamentalist preacher and his too-young wife, Mrs. Pendrake (Faye Dunaway), whose smoldering sexuality is barely repressed behind constant religious bantering that has the feel of rote memorization, not spiritual passion. Jack’s experience with the Pendrakes is the first of many that teach him about the hypocrisy of white civilization and religion, which stand in stark contrast to the film’s depiction of the Cheyenne way of life, which is based on the idea of being centered in the world. This point is hammered home even harder when the film turns violent and Penn shows the atrocities committed against Native Americans by the U.S. Calvary. There are two significant massacre sequences in Little Big Man, in which women and children are slaughtered like animals. The film climaxes in a reverse massacre, that of the U.S. soldiers at Little Big Horn, but it is depicted as the necessary result of the Army’s racist overconfidence. Of course, this is one of the film’s primary weaknesses: In its well-intentioned bid to rework the Western myth to expose the legacy of genocide and racism that supported the U.S.’s “manifest destiny,” it replaces one simplistic dichotomy (whites good, Indians bad) with another (whites bad, Indians good). While screenwriter Calder Willingham (whose collaborations read like a who’s who, including Stanley Kubrick, Mike Nichols, and Robert Altman) gives the Cheyenne a broad range of character types (there’s a bitter young man who resents Jack, a homosexual who spends time with the women instead of the braves, etc.), the white characters all fit neatly into the category of “the absurd”: a snakeoil salesman (Martin Balsam) with whom Jack temporarily joins forces, Jack’s long-lost sister (Carol Androsky) who ditches him because he can’t bring himself to be a vicious gunslinger, Jack’s Swedish wife (Kelly Jean Peters) who is stolen by the Cheyenne and turns into a belligerent shrew, and, of course, General George Custer (Richard Mulligan), who is portrayed as a blustery, egomaniacal fool. All the white characters are absurdist hypocrites who are denied any semblance of humanity. Even Jack himself is something of a joke, relegated mostly to the narrative sidelines as the story of his life unfolds around him without his having much of an effect on it. One can’t entirely blame Penn for overcommitting to his revisionist tendencies. After all, there was some 70 years of racist cinematic mythology to deconstruct, a tall order for any one film (although there was several others working on the same ideological project at this time, most notable Ralph Nelson’s ultraviolent Soldier Blue). As a filmmaker, Penn is firmly rooted in the 1960s counterculture, thus it’s not surprising that he became quickly irrelevant as an artist once the zeitgeist changed and he did not. Little Big Man stands as a testament to the passion of his conviction and his willingness to use his cinematic credibility to reflect meaningfully on the times in which he lived. That the film itself doesn’t play all that well anymore—particularly given its didactic qualities and tonal imbalances that were once revolutionary, but now seem dated—shouldn’t detract from its importance in the history of the American cinema.

Copyright © 2003 James Kendrick | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(2.5)

(2.5)