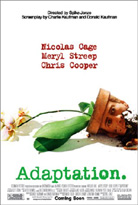

Adaptation.

| Adaptation. is an absurdist black comedy and brilliantly sustained meta-joke on the modern entertainment industry. Screenwriter Charlie Kaufman (Being John Malkovich, Confessions of a Dangerous Mind) plays with the age-old idea of making an “unfilmable” book into a movie by doing just that with Susan Orlean’s 1994 bestseller The Orchid Thief, with the joke being that the subsequent movie ultimately has little to do with the book itself. Rather, it is fictionalized account of the painstaking process Kaufman himself went through in trying to adapt it—although characters and situations from the book are included, as well. Thus, it is a film about adapting a book that is, partially, itself an adaptation. Lost yet? The general screwiness of this film is, in the deepest sense, the source of its pleasure. Adaptation. toys with you and plays itself off as mess, but it is actually an extremely tight film in which all the strands—narrative and thematic—gel together quite beautifully against all odds. This is a film in which reality and fantasy mesh and intermingle to such a degree that it is useless to try to distinguish them—Kaufman’s reality is anyone else’s fantasy and vice versa. Kaufman has taken people who exist in real life and turned them into fictional characters, himself included, while also making up characters and including cameos from movie stars playing themselves (mostly those who starred in Being John Malkovich). The core of the film is Orlean’s book, which is about a man named John Laroche who, along with three Seminole Indians, was arrested for stealing rare and endangered orchids from Florida’s Fakahatchee Strand State Preserve. However, as Kaufman soon learns, there really is no story to be told. Rather, Orlean’s book, expanded from a piece she wrote for The New Yorker, is a free-floating mediation on orchids and her own desire, two things that hardly lend themselves to Hollywood feature filmmaking. That didn’t stop Kaufman from trying, though. In the film, Kaufman has divided himself into two halves by creating twin brothers, Charlie and Donald (both played by Nicolas Cage). (In further blurring the boundaries of reality and Kaufman’s mind, the film credits the screenplay to Charlie Kaufman and Donald Kaufman, even though the latter is purely a figment of the former’s overactive imagination.) Charlie and Donald couldn’t be any different. While Charlie is analytical, repressed, neurotic, and generally at war with himself, Donald is outgoing and relaxed, completely comfortable in his own foolishness. Charlie tries to channel his own neuroses into his work, while Donald goes to weekend screenwriting seminars so he can write his own screenplay, a thriller that he describes in too-adept Hollywood terms as “Silence of the Lambs meets Psycho.” Meanwhile, we also see Susan Orlean (Meryl Streep) working on The Orchid Thief. Despite being a successful journalist with a chic Manhattan apartment and a lively New York socialite life, she has her own trials and tribulations, mainly her sadness at having never felt truly passionate about anything. She finds that passion in the most unlikely of places: in John Laroche (Chris Cooper), who looks like a toothless, backwoods hayseed until he opens his mouth, and you realize he is an extremely intelligent and almost dangerously ambitious and egotistical man (he describes himself as the smartest man he knows) whose passion for orchids descends from a long line of men who died in pursuit of them. Thus, in his screenplay, Kaufman miraculously interweaves Charlie and Donald’s story with Susan and John’s, finding ways to connect them narratively and allowing them to reflect each other thematically. Everyone in the film is desperately searching for something, but in uniquely individualistic ways. Charlie’s voice-over narration invites us into his muddled, troubled mind—the opening credits unspool over a black screen to the sound of Charlie going ’round and ’round in his mind about his various insecurities, most of which revolve around his physical appearance (too fat and too bald, qualities that do not reflect the real-life Charlie Kaufman). Interestingly enough, his twin brother Donald looks exactly like he does, but doesn’t share the same insecurities about his physical appearance, suggesting that Charlie’s anxieties are much more about his own projections than anything in real life. In the final third of the film, Kaufman discards any semblance of reality and drive the narrative headlong into Hollywood action material involving drug running, car chases, shoot-outs, and even an alligator attack, which some critics have mistakenly written off as a flaw when it is, in fact, the film’s most brilliant coup. It works on so many levels that it amazes me that people have assumed it to be Kaufman genuinely selling out the end of the movie. First of all, it works organically with the story—that is, the violence and excitement of the ending don’t feel tacked on, but rather as an extension of the events that preceded it. In some ways, the ending—however absurd—is the only one that could have worked. Secondly, on a meta-level, we have to remember to whom the screenplay is credited (Charlie and Donald). This creates an entirely different level of pleasure in trying to determine which parts of Adaptation were penned by Charlie and which parts were penned by Donald, and the ending has the latter’s signature all over it. Director Spike Jonze, whose directorial debut was Being John Malkovich, is Kaufman’s cinematic soul mate, and he brings the writer’s crazed vision to the screen with panache and visual ingenuity. Never afraid to toy with the boundaries, Jonze finds consistently interesting ways to visualize Kaufman’s ideas, some of which are humorously derivative (again, the ending) and others of which are stunningly effectual (there are two car crashes in the film, both of which explode with the sudden violence and shock that accompany the real thing—in playing with the reality/fantasy divide, Jonze makes you feel like you’re really there). Similarly, the performers deserve a great deal of the credit, particularly Nicholas Cage, who redeems himself from the sluggishness of Windtalkers (2002) and Captain Corelli’s Mandolin (2001) with a truly astounding double performance. As both Charlie and Donald, he looks exactly the same (paunchy with a frizzy, receding hairline), yet his performances as both characters are so complete that we are never for a moment confused as to who’s who—you can see the character in his eyes. Playing twins is something of a stunt, and other performers (notably Jeremy Irons in David Cronenberg’s Dead Ringers) have done it extremely well, but I can’t remember the last time a performer was so perfectly in-tune with the material while playing two discordant characters. Copyright © 2003 James Kendrick |

Overall Rating:

(4)

(4)