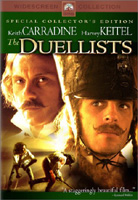

The Duellists

| Bathed in an almost ethereal light, as if it were a moving painting by an Old Master, Ridley Scott's feature debut The Duellists tells the story of a 15-year feud between two very different men in France during the Napoleonic era. Keith Carradine, a favorite of Robert Altman in the 1970s, stars as D'Hubert, a lieutenant in the French army who has the misfortune of being ordered to put another lieutenant, Feraud (Harvey Keitel), under arrest for dueling with the mayor's son and impaling him. For reasons that are never entirely clear, Feraud takes D'Hubert's actions as a personal insult to his honor and challenges him to a duel. And therein begins their 15-year relationship, which consists of a series of duels that, for various reasons, always end prematurely without either having the satisfaction of full victory. The two men couldn't be any more different. While the tall, blonde D'Hubert is rational, measured, and thoughtful, the short, compact Feraud is impulsive and violent, driven by inner demons that are never explained. Based on a 60-page story by Joseph Conrad, The Duellists is primarily about the nature of obsession—simply, why would these two men continue to fight for so many years when neither one of them can even remember the original source of their animosity? (The story's best trick is that the original source is not even worth remembering.) In a way, it works as a cutting metaphor for the nature of war in general, which is underscored by the constant intrusion of warfare into their lives (D'Hubert and Feraud are, after all, officers in Napoleon's army). In fact, the only time they aren't dueling is when France is at war, and at one point they find themselves fighting side-by-side on the frozen Russian tundra during Napoleon's foolhardy invasion. Ridley Scott, now well known for his visionary films such as Alien (1979), Blade Runner (1982), and, more recently, Gladiator (2000) and Black Hawk Down (2001), was then a 39-year-old director of British commercials struggling to make his first feature. Working as his own camera operator, Scott belies the film's meager $900,000 budget with an evocative visual approach. Shot entirely in France using mostly existing locations, The Duellist is a gorgeous film, one of such rapturous beauty that its imagery constantly threatens to engulf the story. Yet, the very beauty of the imagery ultimately works to the story's benefit, as it creates an ironic counterpoint to the irrationality of the ongoing feud between D'Hubert and Feraud. The story is told from D'Hubert's viewpoint—for him, the duels are an invasion in his otherwise staid life. The primary addition to Conrad's story by screenwriter Gerald Vaughan-Hughes is D'Hubert's private life, including his romances with two women, one of whom, Adele (Cristina Raines), eventually becomes his wife and brings him fully into the world of 19th-century aristocracy. Nevertheless, D'Hubert continues to fight Feraud because he is a "gentleman," and that entails defending his honor through violence. Feraud, on the other hand, lives for the duels. They consume him. He is a man constantly at war; even if there is no war to be fought, he will make one. Whatever initial injury to his honor he may have felt in his first meeting with D'Hubert, the very obsession of the duel becomes his primary driving force. Every time he fights D'Hubert and is denied full satisfaction, it fuels his desire to fight again. The story becomes a cat-and-mouse game, with D'Hubert trying to avoid Feraud, who is constantly tracking him down. At one point, D'Hubert sees one of Feraud's associates outside a window and contemplates sneaking out a back door to avoid him. But, he reconsiders, saying, "If he wants me, he'll find me." And isn't that the nature of war? If a nation wants to fight, it will find an enemy or make one in the process. And does war itself ever end? Can it? The nature of the duels between D'Hubert and Feraud is their inconclusiveness—each of them is wounded on several occasions, but never to the point of ending the personal war between them, so it drags on. When the film finally draws to the climatic duel, which finds the two men stalking each other with pistols in the ruins of what was once a chateau, we sense that, however it ends, there will still be an element of open-endedness. Even with one of them dead, a feud that has lasted 15 years, no matter how silly or inconsequential its origins, can never really end, which is perhaps the greatest tragedy of war: Even in victory, there is the defeat of having had to partake in it in the first place.

Copyright © 2002 James Kendrick | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||