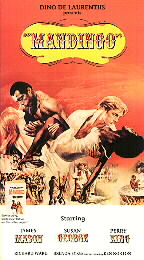

Mandingo

| "Mandingo" has traditionally been seen as one of two things: either a much-needed revisionist look at slavery in the South, or in the words of film critic Leonard Maltin, "a trashy potboiler" that "appeals only to the S&M crowd." Actually, I think "Mandingo" is a strange combination of the two, although it fails on both fronts. It's too trashy to be good drama, but too dramatic to be good trash. The story takes place on a dilapidated Louisiana plantation run by crotchety old Warren Maxwell (James Mason) and his son, Hammond (Perry King). One day in New Orleans, Hammond comes across a slave trader selling a Mandingo named Mede (heavyweight boxer Ken Norton). Although the movie never explains it, a Mandingo is simply the name for Africans who come from the region of the upper Niger River valley. According to the movie, Mandingos were the Rolls Royce of African slaves. Hammond pays top price for Mede and has to fight off others in order to get him. Hammond then spends his time training Mede to be a fighter in money brawls with other slaves. Meanwhile, Hammond has married his cousin, Blanche (Susan George), because she wants to escape her family and he is under pressure from his father to produce a grandchild. Hammond, however, is happier spending nights with his "bed wench," the derogatory name given to female slaves used by their masters for easy sex. It is quickly apparent that Hammond, despite his overt racism, is more in love with his bed wench, a sensitive slave girl named Ellen (Brenda Sykes), than he is with Blanche. Hammond considers Blanche tainted goods because he finds out on their wedding night that another man had "pleasured" her before he did. Of course, it's fine that he's slept with numerous slave girls, but the fact that his wife, a "white lady," had been with another man out of wedlock destroys his capacity to care for her. So Blanche is usually left lonely and sex-starved while Hammond is sleeping with Ellen. Blanche gets back at Hammond by seducing the studly Mede and bearing his child. Hammond and his father cannot stand the idea that Blanche has given birth to a half-black child (although it's okay that Ellen was pregnant by Hammond), so Warren kills the child by letting it bleed to death after birth, and Hammond poisons Blanche. Hammond then finds Mede, shoots him twice in the shoulder, and pushes him into a giant cauldron of boiling water. Yes, you read right: the film ends with Hammond getting his revenge by boiling Mede alive. Judging only by the plot, "Mandingo" is pure sexploitation. The main purpose of the film seems to be getting as many blacks and whites into bed together as possible, with only the slightest commentary on what that would mean in 19th century Southern society. When "Mandingo" was released in 1975, it was still a bit of a shocker to see miscegenation on screen in such a graphic detail; this way the movie could revise cinematic history while attracting large audiences of curious voyeurs. Dramatically, "Mandingo" is weak and unfocused, and historically it's mostly confused. If one were to judge history by this film, it would be easy to walk away with the notion that the entire system of American slavery was based on sexuality, not economics. Not once in the film do we see any of the slaves working, except for a few house servants. The men spend most of the time sitting around, while the sole purpose of a female slave seems to be free sex for the owner. There is historical basis in the notion that slave owners often slept with their female slaves, but "Mandingo's" overwhelming emphasis on this aspect of slavery gives the movie the unpleasant taste of a cheap sex flick (although there's plenty of violence -- fights, vicious beatings, shootings, and the aforementioned human boiling sequence -- thrown in for good measure). Some tried to write off "Mandingo" as a blaxploitation film, one of a number of quickly-made, low-budget films appealing to black sensibilities in the early seventies, but it's not that easy. "Mandingo" was studio-financed by Paramount Pictures, and produced by Dino De Laurentiis, the grandiose Italian producer behind such notorious productions as "The Bible" (1966), the remake of "King Kong" (1976), and the ill-fated "Dune" (1984). The director was Richard Fleischer, a veteran who was best known for several special effects-laden action movies including "20,000 Leagues Under the Sea" (1954) and "Fantastic Voyage" (1966), as well as such superior suspense films as "The Narrow Margin" (1952). The script, based on the supermarket best-seller by Ken Ostott (and the subsequent play by Jack Kirkland), was penned by Norman Wexler, who had been nominated for an Oscar two years earlier for his work on "Serpico." James Mason, Perry King, and Susan George were well-known and respected actors (Mason already had three Oscar nominations under his belt), and Ken Norton appeared to have a promising film career. So why is "Mandingo" so bad? A number of reasons, including the fact that all those experienced filmmakers behind and in front of the camera did a lousy job. Wexler's script is pure poor hokum bordering on the offensive; it combines stereotyped slave-talk ("Yessuh, massuh"), stereotyped Southern white trash talk ("Fer whut're you gittin' outta bed?"), and stereotyped contemporary militant black talk ("If you see me hang, you gonna know you killed a black brother!"). Fleischer's direction is clumsy, especially during the fight scenes, and all the actors give weak performances, especially Susan George whose constant shrieking finally becomes laughable. Nevertheless, credit should be given where credit is due. Despite its exploitative nature, "Mandingo" was one of the first Hollywood movies to take an alternative look at slavery. Until then, there had been a kind of underlying racism in all Hollywood films dealing with slavery. Even classics such as "Gone With the Wind" (1939) can be seen as inherently racist by its glossing over the subject matter. "Mandingo" reassessed the South, and showed that it wasn't all beautiful plantations, green fields, and pretty sunsets. But all this is constantly undermined by the film's negligible point-of-view -- it claims to see things from the black perspective, but the entire narrative focus is on the soap opera tales of the white owners. With a little more maturity and different handling, "Mandingo" might have been an effective, worthwhile film. While it portrays many sensitive aspects of slavery, it never deals with them. The issues the movie brings up are worthwhile, but Wexler's script refuses to move them beyond a surface level of trashily vicarious viewing. There is a great deal of potential in honestly exploring the nature of a sexual relationship between slave and owner, but "Mandingo" never does it. Steven Spielberg touched on that same topic in "Schindler's List" (1993), by looking at a Nazi officer writhing in inner turmoil because of his feelings for a Jewish maid. The difference between that film and "Mandingo" is that Spielberg dealt with the situation in a fair, unexploitive manner that focused on the inherent human dilemma. "Mandingo" is satisfied to simply show some skin, and because of that, its "trashy potboiler" nature overshadows any potential social good it might have accomplished. ©1998 James Kendrick |

Overall Rating:

(1.5)

(1.5)