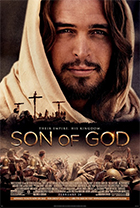

Son of God

|  The fact that the majority of Son of God has been excerpted from The History Channel’s ratings-busting miniseries The Bible (2013) could lead one to the cynical conclusion that the film is primarily a calculated economic move to relieve conservative Christians—who are more often than not aversive to Hollywood movies—of their cash. Given that they are the only audience likely to be interested in such a reverent, unchallenging depiction of the Gospels’ greatest hits and that many (if not most) of them probably already watched the miniseries, which aired only a year ago, it’s hard to otherwise justify the film’s presence at the multiplex. There’s just nothing new here, and what Son of God does it doesn’t do well enough to stand out from all of the similar productions that have come and gone over the decades. The fact that the majority of Son of God has been excerpted from The History Channel’s ratings-busting miniseries The Bible (2013) could lead one to the cynical conclusion that the film is primarily a calculated economic move to relieve conservative Christians—who are more often than not aversive to Hollywood movies—of their cash. Given that they are the only audience likely to be interested in such a reverent, unchallenging depiction of the Gospels’ greatest hits and that many (if not most) of them probably already watched the miniseries, which aired only a year ago, it’s hard to otherwise justify the film’s presence at the multiplex. There’s just nothing new here, and what Son of God does it doesn’t do well enough to stand out from all of the similar productions that have come and gone over the decades.Of course, those inclined toward cinematic treatments of the life of Christ that play like moving picture versions of illustrated Bible storybooks will probably find it very rewarding and reassuring, as it sticks close to the Gospel texts while avoiding anything that might potentially smack of controversy or artistic license. Because I tend to find such films fairly dull (both aesthetically and spiritually), I have been drawn over the years toward the cinematic portraits of Christ that present a unique perspective by defamiliarizing and making anew our conventional notions of the story. Martin Scorsese’s controversial The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) may have veered too far afield of the Gospel account for most, but at least it had the conviction of its desire to grapple with the paradoxical idea of Christ being simultaneously human and divine. Mel Gibson’s similarly controversial (though much more financially successful) The Passion of the Christ (2004) focused on the gruesome details of Jesus’s excruciating physical ordeal at the hands of the Romans, and while some saw it as just a gory horrorshow, people of faith understood it as a reverent meditation on Christ’s sacrifice for humanity. Even Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1962), which I have never particularly cared for despite its highly regarded critical stature, had the audacity to view Christ through the aesthetic lens of neorealism and the ideological lens of Marxism, portraying Jesus as a genuine social rebel. What all of those films have in common, and what I admire about them, is their artistic and personal perspective, which gives them a purpose in cinematically translating the Gospels beyond giving pictorial life to words on a page. Son of God, on the other hand, lacks that artistic perspective. Although nicely shot and capably acted, it mostly feels inert, shackled into moderation and flatness by its fear of offending (and possibly challenging) its core audience. Much like Cecil B. DeMille’s silent-era King of Kings (1927), it abides by a wholly familiar and therefore largely uninteresting visual sensibility, one that feels ripped directly from Sunday School felt boards and stained glass windows. While that is not inherently bad in and of itself, especially given the intended audience, it still forces us to justify the film’s existence given how many similarly produced video versions of the Gospels are already out there. Do we really need another one? Apparently, producers Mark Burnett (Survivor) and his wife Roma Downey (who also plays Mary, mother of Jesus) thought we did. After a brief prologue that gives us fleeting images from the Old Testament, Son of God goes swiftly into Jesus’s birth in a manger before moving into his life as an adult, with more than a third of the film reserved for the depiction of his trial, crucifixion, and resurrection. Along the way we get mostly truncated portrayals of the familiar Gospel stories: the Sermon on the Mount, raising Lazarus from the dead, healing the crippled man lowered through the ceiling by his friends, overturning the money-changers’ tables in the Temple, and so on (interestingly, the sequence in which Christ is tempted in the desert by Satan, who in the miniseries was played by an actor who looked suspiciously like President Obama, has not been included). The Gospels are primarily episodic in nature, which is useful when reading them and using them as a teaching tool, but doesn’t lend itself well to a cinematic narrative, which relies on rhythm and tempo. Son of God moves in fits and starts, and the self-contained nature of so many of the episodes works against thorough emotional engagement. Director Christopher Spencer and cinematographer Rob Goldie, both veterans of television documentaries and made-for-TV movies, make the most of the film’s locations in Morocco, and they generate a few genuinely beautiful images and orchestrate a few memorable moments (one of the best transitions in the film is when the temporary calm following Jesus healing the ear of the Roman soldier attacked by Peter is suddenly disrupted by a bag being thrown viciously over his head; it’s a near-perfect juxtaposition of peace and violence). The casting is generally unsurprising, with most of the actors fitting into familiar visual types that work as shorthand for their characters’ motivations (thus, Joe Wredden’s Judas is narrow faced and shifty, while Adrian Schiller’s Caiphas is short and pompous and Greg Hicks’s Pilate has a face that looks chiseled from hard stone). As is typical of such productions, Jesus is played by a European actor who is both physically attractive and utterly unthreatening (he stands out all the more given that his disciples are played primarily by mixed-race actors of a decided darker hue, which only serves to replicate the misguided notion that Jesus’s divinity is somehow best embodied by having the whitest skin and cleanest clothes on screen). In this case, the role is played by Portuguese actor Diogo Morgado, who looks not unlike a young, more continental Brad Pitt. Morgado’s performance is limited by the filmmakers’ desire to ensure that Jesus has no discernably personality whatsoever (because that might lead to charges of taking too many liberties), which makes one wonder why his disciples would drop their lives to follow him (to be fair, the same problem is evident in Pasolini’s film). Morgado gets to display some emotional intensity as the Passion draws closer and he suffers mightily beneath whip and hammer, but otherwise his performance is characterized primarily by a slightly pleased, kindly smile and soft, dewy eyes that carry no real conviction. Watching him, it is difficult to believe that both the Jewish hierarchy and the Romans were afraid of him to the point that they conspired to orchestrate his death. It makes one wish that that the filmmakers, who I believe to be genuine in their convictions, had been more daring and made something that speaks to someone other than the literal-minded. Copyright ©2014 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © 20th Century Fox |

Overall Rating:

(2)

(2)