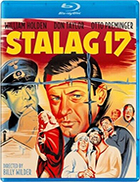

Stalag 17

|  Billy Wilder was never one to be pigeonholed or pinned down. A consummate chameleon who shifted genre with virtually every film he made (and sometimes within the films themselves), Wilder created a body of work that is as diverse as it is entertaining and engaging, chock full of unexpected hits and surprising curveballs that stand as testament to an artist who never felt comfortable unless he was challenging both himself and his audience. Thus, it should come as no surprise that Wilder’s lone war film, Stalag 17, would arrive sandwiched between his acerbic satires Hollywood Blvd. (1950) and Ace in the Hole (1951) and his romantic comedies Sabrina (1954) and The Seven-Year Itch (1955). Of course, Stalag 17 is hardly a conventional war film. Predating Robert Altman’s parodic M*A*S*H (1970) and clearly influenced by Jean Renoir’s humanist Grand Illusion (1938), it is both a mordant comedy and a stark drama, a character study and an invigorating thriller. It hits plenty of by-now-familiar genre points, especially its evocation of the melting-pot assemblage of American types thrown together by the exigencies of war, but it also daringly subverts more than a few expectations and plays up moments of bawdy humor in ways the run headlong into its stark desire for dirty, gritty realism (the film was based on a hit Broadway play by Donald Bevan and Edmund Trzcinski, both of whom spent time in the real-life Stalag 17B during World War II). Set in a German prisoner of war camp in Austria in 1944, Stalag 17 is a kind of whodunit mystery, where the “it” is the person (or persons) ratting to the Germans on the activities of the American soldiers being held prisoner, especially those in Barracks 4, who are a motley assortment or tough-guy caricatures and wise-cracking clowns. Whereas most films of this sort culminate in a complex escape attempt, that is how Stalag 17 begins, albeit with a failed attempt that results in two American prisoners being machine-gunned by the Nazis as soon as they come out of their tunnel on the other side of the barbed wire fence. There is a clearly a rat in the house who is informing on their activities, and there are plenty of men to choose from: the randy, Betty Grable-obsessed Sgt. Stanislaus “Animal” Kuzawa (Robert Strauss, Oscar nominated for his broad mugging); his best friend, the sarcastic Sgt. Harry Shapiro (Harvey Lembeck); the barrack’s appointed chief Sgt. “Hoffy” Hoffman (Richard Erdman); and the barrack’s humorless security officer Sgt. Frank Price (Peter Graves), to name a few. The fact that the film is narrated by Sgt. Clarence Harvey “Cookie” Cook (Gil Stratton Jr.) seems to get him off the hook, but there are no guarantees. The most obvious culprit is Sgt. J.J. Sefton (William Holden), a cynical con artist who has mastered the art of prison camp trade and appears to be a bit too chummy with the German guards (at least chummy enough that he is able to buy his way over to the female Russian prisoner of war camp next door, one of the film’s many barely repressed sexual references). Sefton is the kind of guy you love to hate, and Holden (in an Oscar-winning performance) plays his brazen lack of care to the hilt. It is a minor miracle that we don’t find him utterly despicable. (Andrew Sarris rightly pointed out in his initial dismissal of Wilder in The American Cinema that he was “too cynical to believe even his own cynicism,” which he underscored by pointing out how Holden’s character is softened at the last minute with a boyish smile and a friendly wave after he leaves all his comrades behind.) However, this is precisely the terrain in which Wilder loved to operate, giving us contradictory characters mired in a cleverly balanced generic mishmash that keeps us constantly on our toes (Sarris, to his credit, later recanted most of his dismissal of Wilder). One minute Animal and Shapiro are cooking up an absurd plan to get a peek at the Russian women being deloused in the shower, and the next minute the men are at each other’s throats trying to figure out who the rat is. An all-male barracks dance replete with music and cross-gender performance supplies the film with its most daring slight to the Production Code’s various strictures and also its most significant allusion to Renoir’s earlier masterpiece, although the great director Otto Preminger’s snide camp commandant Oberst von Scherbach is clearly meant to evoke the great director Erich von Stroheim’s parallel character (although I don’t recall von Stroheim having his boots put on him by an underling just to make a phone call to Berlin). There is real danger in Stalag 17, which Wilder establishes with the brutal failure of the opening escape attempt, and he draws out a great deal of suspense when the men work together to hide and then plan the escape for a downed pilot (Don Taylor) who the Germans (rightly) suspect was a saboteur. Following the Broadway play on which it was based, the film also takes the daring gamble of answering the central mystery with more than a third of the story left to go, which dramatically shifts the terrain. It all works (with the possible exception of Cookie’s expository voice-over), proving once again that there was no material Wilder couldn’t make his own.

Copyright © 2024 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Kino Lorber / Paramount Pictures | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3.5)

(3.5)