Children Shouldn't Play With Dead Things (4K UHD)

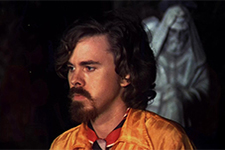

|  As the title suggests, Children Shouldn’t Play With Dead Things is a cheeky subversion of the horror film, specifically the zombie film, which had already become numerous in the four years since the release of George A. Romero’s seminal Night of the Living Dead (1968). Written and directed by Bob Clark from a story idea originally concocted by his friend and fellow University of Miami theatre alum Alan Ormsby (who also plays the lead role), Children doesn’t actually feature any kids, although most of the adult characters act like them. Watching the film, I was reminded of my experience watching Edgar Wright and Simon Pegg’s Shaun of the Dead (2004), which begins as a hilarious slacker comedy before morphing into a straight-up, guts-and-gore horror thriller. Clark does something similar in Children, structuring the first half as a kind of lumbering black comedy before unleashing the ghouls, which, despite the general amateurishness of the production, pack quite a punch. The film follows an oddball community theatre troupe led by a conceited impresario named Alan (Alan Ormsby), who speaks in pseudo-Shakespearean bromides and takes himself very, very seriously. When the film opens, they are arriving at a small island off the coast of Florida whose only use is as a cemetery for the criminally insane. The ostensible reason for their visit is initially buried by both Alan’s pretentious rhetoric and the push and pull between the prankishness and malevolence of his intentions. He refers to all his actors as “children,” which is the starting point of his degrading, controlling relationship with them, and after spinning some campfire stories and pulling some pranks, he reveals that he has every intention of pulling off a blasphemous ritual that involves a druid grimoire and a recently unearthed corpse named Orville (Seth Sklarey). Dramatic realism is largely absent here, but it still works as pure setup. The power of Ormsby’s absurd performance carries the film’s first half on its ostentatious shoulders, conveying through sheer force of will that this pathetic troupe would do almost anything under his guidance—including sitting through a mock ritual in which he “marries” Orville, surely one of the more twisted bits of the film’s subversive humor—even as they clearly loathe him. And, while they think he is full of hot air, it turns out that his incantations have the power of resurrection, as the buried dead begin emerging out of their graves and shambling around, largely unnoticed by the troupe until it is too late and the ghouls have surrounded the deserted cabin in which they are spending the night. At this point, Clark shifts gears and turns Children Shouldn’t Play With Dead Things into a legitimate horror thriller that works despite its minimal budget and limited practical effects (all of which were designed and applied by Ormsby, who added “make-up effects” to his multi-hyphenate credits). It doesn’t match the sheer intensity of Romero’s film, but it works well enough on its own and still manages to weave in some of the macabre humor that dominated the film’s first half. The gore is generally kept to a minimum, as Clark is clearly more invested in the power of atmosphere, which is underscored by the disturbing musical score by Carl Zittrer, who scored all of Clark’s films through the early 1980s before shifting to work primarily as a music editor and supervisor. The cinematography by Jack McGowan veers between being effective and somewhat sloppy, belying the film’s thin budget and lack of resources (not to mention the fact that the entire film takes place at night on a remote island with few light sources). By the time Children Shouldn’t Play With Dead Things was released, the zombie film was already on its way to becoming a cottage industry, at least in their titles. To wit, one of the film’s distributors, Europix International Ltd., took out a full-page ad in Daily Variety touting its “Expertise in Exploitation” in simultaneously releasing “A Triple Avalanche of Grisly Horror” that included Curse of the Living Dead (a retitling of Mario Bava’s 1966 Gothic thriller Kill, Baby, Kill); Fangs of the Living Dead (1969), which was actually a Spanish vampire film starring Anita Ekberg; and Revenge of the Living Dead (a retitling of another 1966 Italian horror film, this one originally titled The Murder Clinic), along with Children and The Body Stealers (1969). Unlike Clark’s feature debut, the gender-bending exploitation trifle She-Man: A Story of Fixation (1967), the film did well during its theatrical release in the U.S. and Canada, with various reports noting that it earned over $1 million on an $80,000 budget. It allowed Clark to continue making a name for himself, which he did with the increasingly ambitious horror films Deathdream (1974) and Black Christmas (1974), the latter of which predated the slasher tropes made famous by Halloween (1978). Clark would go on to what can charitably be described as a most eclectic career, which includes the Sherlock Holmes mystery Murder by Decree (1979), the raunchy teen comedy Porky’s (1981), and the perennial holiday classic A Christmas Story (1983). Interestingly, he would never direct another horror film, although there were reports that he was planning on remaking Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things at the time of his untimely death in a car crash in 2007. Ah, what could have been …

Copyright © 2022 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © VCI Entertainment | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3)

(3)