The Lost Weekend

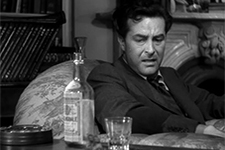

|  Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend, a harrowing adaptation of Charles R. Jackson’s autobiographical novel, was one of Hollywood’s first major social problem films. Released in 1945, a few months after the end of World War II, it looked and felt like no other mainstream film at the time. Its unflinching, unromanticized portrait of the ravages of alcoholism stood in stark contrast to the film industry’s long-standing tendency of treating drinking and drunkenness primarily for comical effect—the town drunk in the Western, the tipsy socialities of social dramas, the drunken buffoons in slapstick comedies. Jackson’s novel, published in 1944, was a literary phenomenon of its time (although it has long since been eclipsed in the popular imaginary by Wilder’s film), and it drew heavily on Jackson’s own repeated bouts with addiction (although the Production Code ensured that his concomitant struggles with sexuality identity stemming from a homosexual encounter in college were left out). Adapted by Wilder and Charles Brackett, who also collaborated on Ninotchka (1940) and later Sunset Blvd. (1950), the film version stays true to Jackson’s sharp depiction of alcoholism even though it manages to stitch together an ending that at least offers the possibility of recovery, whereas Jackson’s novel ends with the suggestion of another bender right around the corner. In one of the great performances of the era, Ray Milland (The Uninvited, Ministry of Fear) stars as Don Birnam, an unemployed New York-based writer who is struggling to get words on the page and drowns his frustrations and sorrows in a steady stream of rye whiskey. When the film opens, he is packing to go on a weekend retreat with his brother, Wick (Phillip Terry), with whom he lives and who has long supported him and tried to help him, as has Helen (Jane Wyman), his girlfriend of the past three years. However, Don ends up skipping on the weekend getaway and instead stays back at Wick’s apartment, ostensibly to begin work on a new novel. Instead, he dives headlong into a multi-day alcoholic bender that finds him more frequently in front of the local bar owned by Nat (Howard Da Silva) then behind the beloved typewriter he eventually wants to pawn to buy more booze. Over the course of the weekend Don scrapes and claws to get more alcohol, at one point stealing a woman’s purse at a nightclub, but more often desperately begging Nat to give him a drink on credit or asking for money from anyone who will listen, including Gloria (Doris Dowling), a local escort who clearly has her eye on him. Don studiously avoids Helen both strategically (she would just try to get him to stop) and out of sheer embarrassment for his dire predicament. He entire existence revolves around his pursuit of alcohol, although the plot pauses long enough to give us several flashbacks to show us how he and Helen met and the early stages of their relationship. Don’s alcoholism is something he has been battling for years, thus this “lost weekend” is not some unique “bottoming out,” but rather just another low point in a years-long war with himself. The Lost Weekend’s depiction of alcoholism was quite progressive for its time, especially when you consider that the American Medical Association didn’t officially deem alcoholism “a major medical problem”—that is, a sickness, rather than a moral failing—until 1956. The film never asks us to judge Don and his actions, but rather to bear witness to them as desperate acts driven by an unquenchable addiction over which he has little control. He is a slave to his desire to imbibe, and it destroys him and everything around him (including Wick’s apartment, which he tears apart at one point looking for hidden bottles). He is both victim and perpetrator of his own demise, which is what makes him so compelling and complicated as a character. We find ourselves rooting for Don to regain control over his life even as we watch it relentlessly spinning out of his control, at one point landing him in the alcoholic ward of a hospital, where he is taunted by a sadistic nurse (Frank Faylen) and surrounded by zombified fellow addicts, many of whom are regulars in the ward. Don later succumbs to withdrawal-induced hallucinations (the so-called “DTs”), which turns the film temporarily into an expressionistic horrorshow. Even as it surges toward the worst, the film dangles the possibility of redemption for Don, thus aligning us with his horrible experience. At the time of its release, The Lost Weekend was a major critical success, winning both the top prize at the inaugural Cannes Film Festival (an award it shared with 11 other films) and the Oscar for Best Picture (only two other films—Marty (1955) and Parasite (2019)—have nabbed both). It was the first American film to win the top prize at Cannes, unless you count Cecil B. DeMille’s Union Pacific (1939), which was given the award in 2002 to make up for the fact that what should have been the inaugural festival in 1939 was cancelled due to World War II). Similarly, Ray Milland picked up the first Best Actor’s Prize at Cannes, as well as the Best Actor Oscar. The Lost Weekend marked the first of Wilder’s films to win Best Picture, a feat he followed 15 years later with The Apartment (1960). He shared the Oscar for Best Screenplay, which he would do again twice with Sunset Blvd. and The Apartment. The film was, of course, not without its controversies, especially with regard to the liquor industry, which was understandably wary about a film that cast their product in such a dour light. As mentioned earlier, the homosexual subtext of the novel also had to be expunged, although there are still remnants floating about, particularly in Frank Faylen’s butch-effeminate portrayal of the alcohol ward nurse. Even viewed today, after so many harrowing films about addiction, The Lost Weekend retains much of its dramatic power, largely due to Milland’s uncompromising portrayal of a man in the thralls of sodden debasement. Alcoholism had never seemed so real and so intense, and virtually every film about the subject since then owes some debt to The Lost Weekend. It is not a perfect film, as its pacing is weighed down by the sometimes awkward flashback structure, and Jane Wyman’s Helen at times seems to be simply too good to be true in her steadfastness and unrelenting commitment to Don, even at his worst. Wyman sells the role (she may be undervalued, in this respect, especially given all the accolades given to Milland), but in retrospect her character seems more of a necessary conceit than a psychological reality. Nevertheless, even with these shortcomings, The Lost Weekend remains a powerful film, one that hits you hard throughout its duration and sticks with you long after it has ended.

Copyright © 2021 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Kino Lorber | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3.5)

(3.5)