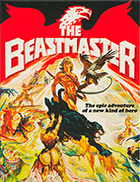

The Beastmaster (4K UHD)

|  Here is a quandary for me as a film critic—a review of Don Coscarelli’s 1982 sword-and-sorcery favorite The Beastmaster. The problem is this: When I was in fourth grade, this was my favorite movie. Back in the early days of cable television, I had taped it off HBO and watched it whenever I could. I had a young boy’s crush on its heroine, played by Tanya Roberts, my friends and I played “Beastmaster” on the playground during recess and drew the pyramid brand on our palms, and I even used it as inspiration for fictional fantasy writings of my own (which, alas, still remain unpublished). So, here I am, nearly four decades later, looking at this film with more experienced eyes—not just of those of an adult, but those of a professional film critic and scholar who has since watched thousands of films and written critically about most of them. I say this not to toot my own horn, but to clarify just how the great the divide is between then and now. There is no doubt that I still enjoy the film immensely simply because I have such fond memories of it from childhood. But, does that make it any good? The truth is, I can’t really tell because it is so ingrained in my mind as one of my favorites that I tend to dismiss its shortcomings and overstate its strengths; it’s too close to my heart, deep in that region that defies rationality, common sense, and, particularly, critical judgment. However, even if The Beastmaster is a “bad movie” in some people’s eyes, I can take comfort that I am not the only one who has enjoyed it over the years. In the late 1980s and ’90s The Beastmaster became a staple of cable television reruns, especially TBS, which seemed to play it at least once a month (the running joke, of course, being that “TBS” actually stands for “The Beastmaster Station”). According to an article in Entertainment Weekly, the ratings for The Beastmaster on TBS ranked just behind Gone With the Wind. Hmmm. Maybe there is something here. The hero of the film is a warrior named Dar (Marc Singer), who has the supernatural ability to understand and communicate with animals. He travels with a four-animal troupe: a black panther named Ruh (actually a Bengal tiger dyed black), two mischievous ferrets named Kodo and Podo, and an eagle named Sharak. Dar can see through the eyes of any of these animals, and he can communicate with them both vocally and telepathically. “They are my friends,” he declares, and each serves its special function: the eagle is his eyes, the ferrets are his cunning, and the panther is his strength. Dar is actually the son of a king named Zed, but he was separated from his father and mother before he was even born (in an elaborate embryonic kidnapping scheme, a witch transferred him from his mother’s womb to the womb of a cow, hence his abilities). Zed was imprisoned, his wife killed, and Dar grew up in the small, rural village of Emor after being adopted by a kindly peasant farmer (Ben Hammer) who raised him to be the same, completely unaware of his royal lineage. Years later, a marauding group of warriors known as the Juns destroys Emor and kills Dar’s adoptive family. So, he sets out on his own to avenge his village, eventually meeting up with two traveling companions (John Amos and Josh Milard) and falling in love with a slave girl named Kiri (Tanya Roberts). Kiri leads him to the great city of Arrok, over which Zed once ruled, but has since been overtaken by the evil Jun high priest Maax (Rip Torn, deliciously chewing the scenery with his rotten teeth), who demands child sacrifices from the general population. Therefore, Dar and company find themselves having to save the city and defeat the Juns, thus fulfilling Dar’s quest for vengeance. All in all, the story in The Beastmaster is familiar sword-and-sorcery fare—an imprisoned king, an evil high priest, marauding warriors—with the only catch being Dar’s animal ties. The film is aided greatly by stunning camerawork by cinematographer John Alcott, who effectively employs many of the same techniques using natural light and fire that won him an Oscar for his work on Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975) to give The Beastmaster a deeper and richer look than most films of its sort. It is also enhanced by an undeniably rousing orchestral score by Lee Holdridge, a veteran composer of some 80 films. Don Coscarelli proves to be an able director, and he makes the most of a modest budget, giving the film a grand scope with limited means. Before The Beastmaster, Coscarelli had already cemented his cult status with the independently produced sci-fi/horror film Phantasm (1978), which followed two children’s films, Jim the World’s Greatest (1975) and Kenny & Company). Since The Beastmaster, he has written and directed three Phantasm sequels, as well as the action thriller Survival Quest (1988) and the cult horror-comedies Bubba Ho-Tep (2002) and John Dies at the End (2012). It is well known that, during production of The Beastmaster, Coscarelli and his co-writer Paul Pepperman (who also co-produced the film) butted heads with executive producer Sylvio Tabet, who eventually wrested control of the film from them. Coscarelli was barred from the editing room, thus the final cut of the film is not what he intended, although he does not dismiss it entirely. It is perhaps poetic justice that, once Tabet was allowed to have complete control as writer, producer, and director, he gave us Beastmaster 2: Through the Portal of Time (1991), one of the worst fantasy movies ever—a truly unwatchable embarrassment. Tabet also went on to executive produce a made-for-TV sequel, Beastmaster III: The Eye of Braxus (1996), and the 1999–2002 television series, as well as co-write a 2009 novel, Beastmaster: Myth. As far as the acting goes, it works well enough. The dialogue is vaguely better than what you find in most sword-and-sorcery movies, but it’s still bare. Marc Singer, who was relatively unknown at the time, having appeared in supporting roles on television series and made-for-TV films over the previous decade (including several Shakespeare plays), makes for an amiable hero; he is toned and muscular and intensely physical, but not awkwardly muscle-bound, and he shows real traits of humanity, intelligence, and humor, as does Jon Amos as Seth. Despite my previous crush, I now fully recognize that Tanya Roberts is not a particularly great actress, something she certified several years later with the laughable Sheena (1984) and her turn as a James Bond girl in one of the series’ worst entries, 1985’s A View to a Kill (although she redeemed herself from her spate of straight-to-video erotic thrillers in the late ’90s with a comical turn as an airhead would-be feminist housewife in the TV series That ’70s Show). Veteran character actor Rip Torn, on the other hand, dominates every scene he’s in as the evil Maax (a role for which Coscarelli had originally wanted to cast Klaus Kinski). With his rotted teeth, squinty eyes, hawkish nose (a prosthetic that he insisted on having), and harsh tone, Torn creates a perfect arch nemesis—ratty, manipulative, and just this side of outright camp. The Beastmaster boasts some well-choreographed swordplay and fight scenes, especially two rousing finales, one of which consists of Dar clamoring up the steps of a giant pyramid to save Kiri from being sacrificed. It is a classic B-movie scenario, bringing the battle to a cliffhanger moment in which Dar’s past is violently revealed to him before he dispatches the enemy. The animals consistently work well into the action, especially the two ferrets, who are much more useful than you might think (plus, they add a “cute factor” to all the violence). As the interminable B-movie cineaste Joe Bob Briggs so memorably put it when he hosted the film on TNT’s MonsterVision in the late 1990s, The Beastmaster is “the only movie to combine child sacrifice with ‘aren’t the animals cute’ scenes. It’s a movie that can be enjoyed equally by the Michigan militia and the Westminister Kennel Club.” So—what to make of it all? For its genre, The Beastmaster is top of the list. Of course, that’s not saying much since its genre is that great glut of mostly cut-rate Dungeons & Dragons-inspired fantasy movies that flooded theaters and then cable channels in the early- to mid-’80s, including such duds as Deathstalker (1984) and Red Sonja (1985). John Milius’ Conan the Barbarian (1982) is generally celebrated as the best of the bunch, but only because it has the pedigree of dating back to true pulp serials from the 1930s. For my money, though, The Beastmaster is more creative, better filmed, and just plain more fun. Thus, even when I do my critical duty and put The Beastmaster under severe scrutiny, I still can’t help but think that it is simply good old-fashioned entertainment. My nine-year-old inner child is telling me this is a five-star masterpiece on a four-star scale, but my more mature critical self is telling me it is a two-star cable movie. So, I guess I’ll just go somewhere near the middle and give it three stars. Why not? It has a daring hero, a beautiful heroine, a lot of action, and some clever animals all filmed in luscious golden hues by an Oscar-winning cinematographer. What more you could ask for on a Tuesday-night TBS rerun?

Copyright © 2021 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Vinegar Syndrome | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3)

(3)