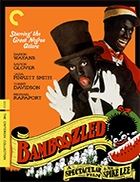

Bamboozled

|  Spike Lee may veer into overstatement when he has the central character of Bamboozled, an outwardly successful, but inwardly self-loathing, African-American television executive, recite in voice-over narration at the beginning of the film the dictionary definition of satire: “a literary work in which human vice or folly is ridiculed or attacked scornfully.” I guess it just goes to show that Lee has become so accustomed to stirring up controversy and inciting the wrath (and misunderstanding) of conservative critics that he feels the need to explain himself before the film hits the two-minute mark. It is a defensive move, to be sure, but if there has ever been a film that is in need of defense, it is Bamboozled, which is arguably Lee’s most incendiary attack on the treatment of race in America. Bamboozled is a sharp-edged, if somewhat heavy-handed, satire about popular culture and the portrayals of blacks in the mass media. Those not familiar with the history of black representation on screen and stage (or those who have purposefully chosen to forget it) will likely argue that Bamboozled overshoots its target. After all, Lee’s central conceit, the repopularization of blackface, veers deep into potentially dangerous territory. Blackface was a common practice of the 19th and much of the early 20th century, when white actors portrayed African-Americans by painting their faces black with paste made from burned cork and water. It has long been considered one of the most demeaning ways to portray African-Americans, especially because it is inextricably linked to racist depictions of blacks as comical, lazy, and ignorant. Lee’s point throughout Bamboozled is a strong one, and the use of blackface, while extreme, serves as a readily inflammatory symbolic gesture of how the racism of yesterday still exists, but in different forms. He floods the screen with black representations in entertainment over the past century, from D.W. Griffith’s vicious black rapist in The Birth of a Nation (1915), to comical caricatures like Amos ‘n Andy and Stepin Fetchit, to racist Bugs Bunny cartoons, to the white-meets-black upward mobility of The Jeffersons. This is an issue about which Lee has thought for a long time and has informed his art from the very beginning (his first film as a graduate student at New York University, The Answer [1980], was a rebuke to his professors’ teaching the aesthetic and narrative innovation of The Birth of a Nation without addressing its racist content). It would be easy to throw all that up on screen and lament how terrible black representations used to be while basking in the glory of our post-1960s liberal awakening. Yet, as always, Lee wants to call that trump card, and he does so forcefully by pointing out that, while the characterizations of African-Americans may not be as blatantly racist as they once were, in many ways little has changed. As one character puts it, “The network does not want to see Negroes on television unless they are buffoons.” In other words, blackface is blackface, even if no make-up is involved. The film’s central character is Pierre Delacroix (Daman Wayans), a black TV writer who comes up with the idea for a new program that is actually a reversion to turn-of-the-century minstrel shows that had black and white actors in blackface playing comically ignorant characters for laughs. Delacroix, whose secret desire is to be fired because he is fed up working with the network, imagines a new variety show titled Mantan: The New Millennium Minstrel Show that has all the racist stereotypes and humor of 100 years ago, right down to the setting on a Southern plantation complete with watermelon patches. When Delacroix first comes up with this idea, it is to prove his point that no one wants to see realistic portrayals of African-American characters in the media. Yet, his polemic backfires when the show becomes a surprise hit, and Delacroix is left feeling like Victor Frankenstein, having unleashed a monster that he can no longer control. For the two key roles in Mantan, Delacroix pulls two young black performers from the street where they earn nickels and dimes performing on sidewalks. Manray (Savion Glover), the gifted tap dancer, is renamed Mantan, and his partner, Womack (Tommy Davidson), is renamed Sleep’n’Eat and turned into his sidekick (their stage names are references to the black comic actors Mantan Moreland and Willie Best, the latter of whom was credited throughout the 1930s as Sleep’n’Eat). Manray and Womack, like the actors from whom their stagenames are derived, go along with the blackface minstrel show because they need the money, but it is obvious from the start that they are uncomfortable with the idea. This is also true of Sloan Hopkins (Jada Pinkett Smith), Delacroix’s assistant, who ends up as the film’s tortured conscience. The show is, however, enthusiastically supported by Dunwitty (Michael Rapaport), the senior vice-president to whom Delacroix reports. Dunwitty, who is white, claims to have more in common with black culture than Delacroix does because he grew up with black people and has a black wife and two biracial children (“Brother man, I’m blacker than you,” he proclaims). Dunwitty speaks in a bizarre amalgam of business-speak and street lingo, and he openly mocks the Harvard-educated Delacroix for being too “white.” The vexed question of who is black and who is white is one of Bamboozled’s most interesting issues. Lee has often been unjustly accused of being a reverse racist because his art is so intricately bound up in uncomfortable questions about the role of race in America, but it should be made clear that Bamboozled is in no way a diatribe against white people. In fact, Lee seems to go out of his way not only to question the dividing lines between blackness and whiteness (especially in the tense relationship between Delacroix and Dunwitty), but also to show that both blacks and whites are responsible for making Mantan a hit show. When the camera pans out into the television audience, all of whom are gleefully made up in blackface, it is quickly apparent that there are people of all races happily partaking in the demeaning humor of the minstrel show. In fact, one of Lee’s most scathing critiques is that African-Americans are often implicated in their own degradation in the media. What Bamboozled shows most clearly is the way African-Americans have been, and continue to be, commodified in American culture. As blacks in America were once literal commodities—properties to be sold and owned—the cruel logic dictates that, since the end of slavery in 1865, mainstream culture would have to find new ways to commodify them. Lee stresses the persistence of this trend, as he makes strong connections between caricatured black trinkets and toys from the turn of the century and modern-day advertising for malt liquor and “Timmi Hillnigger” apparel—a thinly veiled attack on fashion designer Tommy Hilfiger. Bamboozled is not, however, without its flaws. I have some reservations about the performances, most notably Damon Wayans’s decision to play Delacroix in an overly stiff, almost cartoonish manner that resembles his imitation of “white people” on In Living Color, the late ’80s comedy sketch series where he first made his mark. It may have looked good on paper within the framework of a satire, but the stark immediacy of the film (enhanced by Lee’s use of digital video instead of film) makes the performance seem showy and out-of-place and takes away from the character’s complexity and emotional resonance. Lee’s making the film an overt satire was a smart move because it gives him room to push the envelope in ways that drama or straight comedy would not have allowed. However, he gets caught up in the same logic that drove Do the Right Thing (1989), which demands that the narrative end in violence. In Do the Right Thing, it worked because that was the entire point of the film: how actions and words that seem so insignificant in isolation build and build upon each other until they have to explode. In Bamboozled, everything is so over-the-top from the outset that the devolution into violence at the end seems like a desperate bid to assert significance. Lee doesn’t seem quite comfortable with the idea that the satire itself is enough, even though it is precisely the jarring nature of his satire that makes the point most saliently.

Copyright © 2020 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © The Criterion Collection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3)

(3)