Teorema

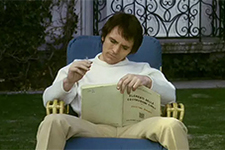

|  How you feel about Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema will be determined largely by how willing you are to apply heavy import and meaning to a vague, potentially silly premise. Virtually everything that happens in Teorema is either absurd, empty, or pretentious, but because Pasolini is an avowed auteur who has written extensively in theoretical, political, and poetic veins, we have a duty to take what he has put on the screen seriously, no matter how ridiculous it is on its face. Reading years of critical and scholarly responses to Teorema is much more engaging and interesting than the film itself because most of its meaning has to be inserted by the viewer. Many have written that Teorema is open to multiple interpretations, but really it is open to virtually any interpretation because Pasolini leaves it wide open in every regard. The story centers around a bourgeoise Milanese family into whose midst arrives a mysterious visitor (Terence Stamp). The visitor has no name and no discernible characteristics aside from being handsome and lithe, saying very little, and having a penchant for sitting in a way that maximizes the view of his crotch, which apparently arouses the lust of every member of the family: First the teenage son Pietro (Andrés José Cruz Soublette), an awkward, would-be artist; then the gorgeous middle-aged mother, Lucia (Silvana Mangano); then the quiet, reserved teenage daughter, Odetta (Anne Wiazemsky); and finally, the father (Massimo Girotti), a stern factory owner. Oh, and he also turns on the family’s maid, Emilia (Laura Betti ), who is deeply religious. One by one the visitor seduces each member of the household, after which they become aware of how empty and awful their lives are, which sends them into fits of madness, catatonia, and/or despair (except the son, whose artistic wells are suddenly opened, and the maid, who returns to her earthly village and becomes a saint with the ability to levitate and heal the sick). Just describing it sounds patently absurd, especially when you consider that most of this transpires with little or no dialogue so that we learn virtually nothing about the characters except the sudden, canned realization of their own despair. Sex with the visitor somehow frees them, but only to recognize their fundamental emptiness. But, of course, we’re not supposed to read any of this literally. Sex isn’t really sex, the characters are all symbolic stand-ins, and every action is just a reference to something else. Pasolini, at the time of the film’s production, was deep into his own world of theorizing, and he presented Teorema as a kind of theoretical test case for how a film could engage the symbolic and the allegorical. The title, which means “theorem,” alludes to the fact that Pasolini uses the narrative as a means of “proving” his hypothesis about the Italian bourgeoise—that essentially they are vacant and fragile and meaningless and that the introduction of something outside their control will cause them to collapse. The very fact that this class-based allegory is at best rudimentary has to be acknowledged (a Marxist who loathes the wealthy? Imagine that!), as does the fact that other filmmakers have used that foundation to make much more intellectually stimulating and cinematically engaging films (you can pick any number by Luis Buñuel, including 1962’s The Exterminating Angel and 1972’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoise). Like some of his later films, particularly the three films in the “Trilogy of Life,” Teorema is aesthetically sloppy, alternately beautifully framed shots with lazy compositions and ragged editing that often cuts away too quickly or lingers for too long. Pasolini is no dummy—he was really quite brilliant, in fact, and an able practitioner of many arts—but he was also susceptible to falling prey to his fascinations, obsessions, and desires to the point of myopia. For him, Stamp’s visitor is some kind of divine intervention—either Christ figure or demon, who knows?—but only because he tells us. The film itself simply presents Stamp’s visitor as physically occupying the same space as the family and interacting blandly with its members; the only real hint of something otherworldly is the absurdist loon played by Pasolini regular Ninetto Davoli who shows up with telegrams announcing the visitor’s arrival and sudden departure. By the time we have gotten to the end of the film and the last family member is stumbling stark naked across a barren, volcanic landscape raging at the meaninglessness of it all, the film could mean anything, which is why many critics and art-house aficionados have found it a transfixing object over which to obsess. I can’t help but find it, in the words of critic Pauline Kael, “intolerably silly.”

Copyright © 2020 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © The Criterion Collection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(2)

(2)