And Life Goes On (Zendegi va digar hich)

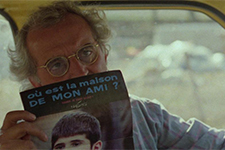

|  Abbas Kiarostami’s And Life Goes On (aka Life, and Nothing More …), the second film in his “Koker Trilogy,” follows, builds on, and reveals the fiction of his earlier film Where is the Friend’s House? (1987). Like his previous film, Close-up (1990), it works as a self-conscious deconstruction of the cinema itself, uncovering in ways both subtle and overt how movies are fictions that nevertheless help us recognize fundamental truths. Kiarostami had started his career making documentaries in the 1970s, so he was steeped in that tradition before he moved into fictional features, many of which bore the aesthetic traces and ideological preoccupations of his time making nonfiction films. Where is the Friend’s House, which unfolds over a 24-hour period, follows in neorealist fashion a young boy trying to return a schoolmate’s notebook lest he be expelled the next day. It is about seemingly insignificant instances in a single life, yet it carries a deep, profound humanistic insight and sense of fundamental decency. Kiarostami shot the film in and around the village of Koker, which in 1990 was hit by the devastating Manjil-Rudbar earthquake, which killed anywhere from 30,000 to 50,000 people and left entire villages in ruins, including Koker. And Life Goes On tells the fictionalized story of Kiarostami’s return to Koker in the immediate aftermath of the quake to find out what happened to the children who starred in Where is the Friend’s House?. Farhad Kheradmand plays an unnamed film director who, along with his young son Pouya (Pouya Payvar), drives from Tehran into Northern Persia, the epicenter of the quake, trying to get to Koker—or what remains of it. Along the way they must traverse broken and closed roads, miles and miles of rubble, and thousands of men, women, and children who have been displaced by the disaster. Like Where is the Friend’s House, the film unfolds over a single day. The director and his son’s journey is punctuated regularly by frustration as they find it impossible to get where they are going due to the devastation, but it is also peppered with glimpses and insights into the people who were affected by the disaster, including an elderly woman who gives them directions, a newly married man (who will become the subject of Kiarastomi’s final film in the trilogy, Through the Olive Trees), a young man setting up a TV antennae so the others in the hastily constructed tent village can watch the World Cup, and a local man who played a central role in Where is the Friend’s House. The director’s interactions with this man give the film its most direct commentary on the nature of filmmaking, as he complains about how he was depicted in the previous film, specifically how he was given a humpback and made to look much older than he was. The film is replete with imagery that similarly comments on the nature of filmmaking, as Kiarostami juxtaposes a handheld, documentary-like aesthetic with images that are carefully composed and constructed, such as the long shot of a hillside that has been cracked open in numerous places by the quakes, the vertical lines of broken earth looking like nothing so much as tears streaming down the grass. The film director’s interactions with the people whose paths he crosses paint a complex portrait of human suffering, dignity, and perseverance. At times we acutely feel the horrors of the disaster, as Kiarostami’s camera tracks across seemingly endless vistas of collapsed buildings along the side of the road. At other times, we are surprised by the resilience of the people hardest hit, as they do their best to reclaim whatever joys they can from the rubble around them. As the young man putting up the TV antennae says, “Life goes on,” neatly summarizing the film’s central theme without sinking into a mire of clichés. The nonchalant manner in which he says it and the film director’s innate understanding of how he and the others find solace in international soccer (as does his young son) puts into sharp relief the complex nature of human response to tragedy. Kiarostami never shortchanges the enormity of the earthquake’s devastation, but his goal is not to wallow in what has been lost, but to seek out what still survives and cherish it, which is why the film centers on the search for the child actors. The possibility of finding them safe and alive provides the silver lining of hope that makes life worth continuing.

Copyright © 2019 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © The Criterion Collection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3.5)

(3.5)

And Life Goes On is available as part of “The Koker Trilogy” boxset, which also includes Where is the Friend’s House? (1987) and Through the Olive Trees (1994).

And Life Goes On is available as part of “The Koker Trilogy” boxset, which also includes Where is the Friend’s House? (1987) and Through the Olive Trees (1994).