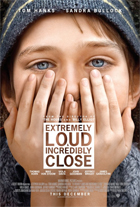

Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close

|  In the 10 years since the planes crashed into the World Trade Center towers and the Pentagon, Hollywood has treated 9/11 much like it treated the Vietnam War four decades ago: largely avoiding it. While other forms of artistic expression, from music, to theater, to painting, have tackled the topic in myriad ways, the movies have kept their distance. Granted, there have been some notable independent and international productions and scores of television documentaries, but the major studios have given us only a smattering of theatrical films that deal directly with the horrors and heroism of September 11 (Paul Greengrass’s immensely moving United 93 and Oliver Stone’s muddled World Trade Center, both from 2006), or the emotional aftermath (Mike Binder’s 2007 dramedy Reign Over Me). In the 10 years since the planes crashed into the World Trade Center towers and the Pentagon, Hollywood has treated 9/11 much like it treated the Vietnam War four decades ago: largely avoiding it. While other forms of artistic expression, from music, to theater, to painting, have tackled the topic in myriad ways, the movies have kept their distance. Granted, there have been some notable independent and international productions and scores of television documentaries, but the major studios have given us only a smattering of theatrical films that deal directly with the horrors and heroism of September 11 (Paul Greengrass’s immensely moving United 93 and Oliver Stone’s muddled World Trade Center, both from 2006), or the emotional aftermath (Mike Binder’s 2007 dramedy Reign Over Me).Stephen Daldry’s Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close proudly marches into that void with an air of self-importance seemingly confirmed by its recent Best Picture Oscar nomination. Daldry’s presence behind the camera should come as little surprise; after his directorial debut with the enjoyably unassuming Billy Elliot (2000), each of his subsequent films has followed a strict, Oscar-baiting formula centered around adapting a recent book with strong literary pedigree that tackles a big, weighty subject. In The Hours (2002), he took on the general topic of female subjugation and rounded it out with subplots about AIDS and suicide, while The Reader (2008) wooed art house crowds with its glib mixture of frank sex and Holocaust guilt. Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close fits right in and continues Daldry’s trajectory of increasingly indigestible pretension, although he exchanges earnest morbidity for a mixture of cloying sentimentality and offbeat humor. The story is ostensibly about the difficulty in coming to grips with senseless loss, in this case a mother and 11-year-old son’s loss of their husband and father in the World Trade Center on 9/11. Yet, nothing and no one in the film feels even remotely genuine; virtually every scene and every character comes across as an elaborate construction of “clever” conceits and melodramatic baiting. Viewing Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close as a film about post-9/11 loss is like viewing Forrest Gump (1994) as a film about the experience of being a Vietnam veteran. Forrest Gump comparisons are actually quite apt, as Daldry has recruited Gump screenwriter Eric Roth to adapt Jonathan Safran Foer’s popular sophomore novel and cast Forrest Gump himself, Tom Hanks, to play the lost husband and father. Daldry, unfortunately, doesn’t have Robert Zemeckis’ skills in mixing human pathos into absurdist storytelling and developing appealing protagonists. In fact, the biggest flaw in Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close is that its protagonist, Oskar Schell (Thomas Horn, a former Jeopardy! Kids Week champ), is not particularly likeable and is at times downright grating. He earns immediate sympathy because (1) he is a child and (2) he has lost his father, but those are just plot points that could be inflected in any number of ways to define and develop his character. Not having read the original novel, which is told partially in Oskar’s voice, I don’t know how he works on the page, but on the screen he does not work at all. We know that Oskar is incredibly intelligent and precocious, but also that he has interpersonal problems (in his voice-over narration he tells us that he was once tested for Asperger Syndrome and that the results were “inconclusive”). He has an extremely close relationship with his father, who is apparently nothing less than an absolute saint who spends most of his time concocting “reconnaissance” missions for Oskar around Manhattan that keep the boy occupied and also help him come out of his shell. Oskar, whose general rudeness is his defining characteristic, seems to have little interest in his mother (Sandra Bullock), a trait that borders on outright contempt later in the film when he bluntly tells her he wishes it were her who died in the towers rather than his sainted dad. The emotional cruelty heaped on Bullock throughout the film is brutal, and a last-reel revelation that is intended to cast her in a new light in Oskar’s eyes is the phoniest conceit in a film full of them (there are also all kinds of bizarre plot contrivances and holes, such as Oskar’s determination to identify his father’s face in the pixilated blow-up of a falling body even though it is made clear late in the film that he knows he was killed when the tower collapsed). Most of the story follows Oskar as he combs the city trying to find the lock that fits a key he found in his father’s closet a year after his death. Misunderstanding the key as the first clue in his father’s last reconnaissance mission, Oskar proceeds to track down and interview the hundreds of people across the five boroughs with the last name “Black” (the key was in an envelope with the word “Black” on it). This brings him into contact with a number of characters, including a married couple (Viola Davis and Jeffrey Wright) in the midst of breaking up when Oskar knocks on their door and a mysterious elderly man known only as the Renter (Max Von Sydow), so named because he is renting part of Oskar’s grandmother’s apartment. The Renter, who has not spoken in decades and communicates only via written notes on a pad and a “yes” and “no” tattooed on his palms, becomes Oskar’s companion during the search, and Von Sydow’s elegant and moving silent performance is virtually the only thing about the film that feels vaguely real. Although we are meant to identify emotionally with Oskar, Daldry makes it all but impossible because he is under the delusion that Oskar’s scrappy determination overpowers his self-centered and irritating behaviors and attitudes. Daldry’s films tend to center on complex, bewildering characters, which tempts us to read depth where there is simply confusion. You can’t help but admire Oskar’s childish determination to solve what he thinks is his father’s last mystery, and most of us can identify with his frustration with the senselessness of the 9/11 carnage. Yet, his character constantly (almost defiantly) gets in the way of the elements in the film that actually work—his determination comes off as condescension—thus pushing us away when he should be drawing us in. The result is a climactic emotional catharsis that doesn’t feel gratifying or earned, but rather fabricated, a final bit of stickiness in a movie that is only convincing as a vehicle for bullying the most susceptible Oscar voters. Copyright ©2011 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Warner Bros. |

Overall Rating:

(1.5)

(1.5)