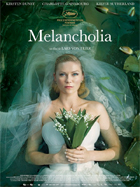

Melancholia

|  Lars von Trier’s Melancholia is being praised by many as a genuine late-season masterwork, but it strikes me as little more than an overlong, self-indulgent mishmash of gorgeous imagery and nihilistic overload. Von Trier has forged the majority of his career wallowing in darkness and despair, but because he lacks the spiritual depth and commitment of his Scandinavian forebears Carl Theodor Dryer and Ingmar Bergman, his films often feel pointless in their despondency, inflicting emotional punishment on the audience that pales only in comparison to the ugliness he often metes out to his female martyr-protagonists. Melancholia is perhaps the grandest and most ambitious of his efforts, and at times it threatens to become something grandly terrible and moving. And, as an epic metaphor for the devastating effects of depression (something that both von Trier and his lead actress Kirsten Dunst have both battled), the film is not without its merits, although said merits are often stretched to their breaking point or overshadowed by meandering narrative digressions and inexplicable human behavior. Lars von Trier’s Melancholia is being praised by many as a genuine late-season masterwork, but it strikes me as little more than an overlong, self-indulgent mishmash of gorgeous imagery and nihilistic overload. Von Trier has forged the majority of his career wallowing in darkness and despair, but because he lacks the spiritual depth and commitment of his Scandinavian forebears Carl Theodor Dryer and Ingmar Bergman, his films often feel pointless in their despondency, inflicting emotional punishment on the audience that pales only in comparison to the ugliness he often metes out to his female martyr-protagonists. Melancholia is perhaps the grandest and most ambitious of his efforts, and at times it threatens to become something grandly terrible and moving. And, as an epic metaphor for the devastating effects of depression (something that both von Trier and his lead actress Kirsten Dunst have both battled), the film is not without its merits, although said merits are often stretched to their breaking point or overshadowed by meandering narrative digressions and inexplicable human behavior.The film begins with a 10-minute series of slow-motion tableaux that, in hindsight, effectively summarize the film, albeit in often symbolic form. The grandeur and intensity of these dreamlike images, some of which take place on earth and some of which are unfolding in the cosmos, is intensified by von Trier’s use of the “Prelude” from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, a recurring musical motif that gradually loses its effectiveness throughout the film. The final image of these opening tableaux is Earth smashing into a much larger planet, a foreshadowing of the film’s apocalyptic conceit that humanity--the only life in the universe, according to the film--is threatened by a rogue planet that emerges from behind the sun and appears to be on a trajectory toward our planet. For the first half of the film our imminent demise is left simmering on the backburner in favor of an extravagant, all-night wedding reception for Justine (Kirsten Dunst) and Michael (Alexander Skarsgård), which is being held at the palatial country estate owned by Justine’s level-headed sister Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg) and her wealthy husband John (Kiefer Sutherland), who is given to much grumbling about how much the affair is costing him. If there is a point to the film’s first hour, it is the systematic extinguishing of any sense of possible happiness for Justine, who has clearly battled and mostly lost to depression all her life. It is hard to blame her, though, as her father (John Hurt) is blissfully disengaged from the world and her mother (Charlotte Rampling) is so bitter and poisonous that she can’t contain her disgust with the idea of marriage during her toast. Justine attempts to engage in the merriment, but most of the time she is wandering off alone, disappearing to take a bath for no apparent reason, or, in the final coup de grace, having sex with the young man (Brady Corbet) hired by her relentless boss (Stellan Skarsgård) to follow her around the reception and try to pry from her a “tag line” to go with his company’s latest advertising campaign. The litany of bizarre behavior on display throughout the reception serves as a kind of rundown of interpersonal failure: anger, bitterness, despair, greed, and so on. It is essentially von Trier’s laundry list of why no one gets along and, as a result, there is really little to lose if humanity comes to an apocalyptic end. Even when characters try to connect--the poor newlywed husband being the best example--their failure is imminent and therefore pathetic. It’s hard to feel for Michael’s inability to get through even one night of marriage with his new bride, and Justine sums it up perfectly at the end of the disastrous evening: “What did you expect?” The question might as well be posed by von Trier to the audience as we move into the second half of the film, which finds Justine, having retreated into a depressive state in which she does little more than sleep, act catatonic, and complain that meatloaf tastes like ashes, living with Claire and John. Claire is anxious about the discovery of Melancholia, the aforementioned rogue planet that is set to pass Earth in five days. John assures her that the world’s scientists agree that it will just “pass by,” and is actually excited about the event, looking constantly through his telescope and helping their young son Leo (Cameron Spurr) construct a rudimentary device to determine if the planet is getting nearer or further away. The juxtaposition of Claire’s increasing anxiety about Melancholia’s arrival and Justine’s trance-like calm are flip sides of the same coin: Everything will be destroyed, so it doesn’t much matter if you’re flipping out or checking out. And that, ultimately, is why Melancholia fails to engage emotionally or philosophically: It’s a stacked deck, with von Trier showing us our demise in the first 10 minutes and then spending the next 125 minutes dragging us slowly (some might say excruciatingly) through the final days in which said demise is all but justified by the lack of humanity on-screen. Von Trier’s epic approach to the material is its own undoing, as it muddies up the metaphorical possibilities linking the blue planet Melancholia and Justine’s psychological blues, both of which can be hidden temporarily, but ultimately become overwhelming. Kirsten Dunst’s performance has been rightly celebrated (she won the Best Actress prize at Cannes), as she conveys with consistent power the debilitating depths of depression; she is at her best in the reception scenes where she is trying so hard to be “normal” and “happy,” but consistently failing. When she disappears for long stretches during the film’s second half, we lose connection with her, much to the film’s detriment. It also doesn’t help that Melancholia is being released the same year as several other, better movies about similar themes. Consider that we have already seen Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life, which makes genuine, heartfelt, and spiritually moving connections between the banality of everyday life and the vastness of the cosmos; Jeff Nichols’s Take Shelter, which truly illuminates a tortured psyche via an impending apocalypse; and Mike Cahill’s Another Earth, which also uses the idea of a rogue planet suddenly appearing in our solar system, but to explore the all-too-human desire to erase our past mistakes. What those films all have in common is an abiding sense of humanity, a desire to use a fantastical/science fiction concept to illuminate what it means to be human, rather than simply wallow in the pits of despair, however beautifully rendered those pits may be. Copyright ©2011 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Magnolia Pictures |

Overall Rating:

(2)

(2)