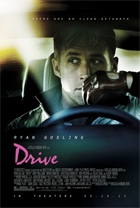

Drive

|  Drive, which won Nicolas Winding Refn the Best Director prize at Cannes last spring, is a sharply etched, finely tuned homage to the existential road movies of the 1970s like Vanishing Point (1970) and Two-Lane Blacktop (1971) in which the nature of human existence was fused with the open road. Weighted with steely silences and sudden explosions of graphic violence, Drive confronts and dismantles our expectations with a hardened confidence that is all too rare in contemporary Hollywood filmmaking (are we reaching a point in Hollywood, as we did in the 1960s, where we have to import European directors to breathe new life into old genres?). The Danish-born Refn has already wowed film festivals and European audiences with his previous films, which include Bronson (2008) and Valhalla Rising (2009), and if there is any sense in the universe, Drive will cement his reputation stateside and ensure a steady stream of work that allows him to remake the familiar with his mix of formal austerity and tonal playfulness. Drive, which won Nicolas Winding Refn the Best Director prize at Cannes last spring, is a sharply etched, finely tuned homage to the existential road movies of the 1970s like Vanishing Point (1970) and Two-Lane Blacktop (1971) in which the nature of human existence was fused with the open road. Weighted with steely silences and sudden explosions of graphic violence, Drive confronts and dismantles our expectations with a hardened confidence that is all too rare in contemporary Hollywood filmmaking (are we reaching a point in Hollywood, as we did in the 1960s, where we have to import European directors to breathe new life into old genres?). The Danish-born Refn has already wowed film festivals and European audiences with his previous films, which include Bronson (2008) and Valhalla Rising (2009), and if there is any sense in the universe, Drive will cement his reputation stateside and ensure a steady stream of work that allows him to remake the familiar with his mix of formal austerity and tonal playfulness.Like the lead characters in its ’70s predecessors, the nameless protagonist in Drive (Ryan Gosling) is an enigma--both everyman and no man. We learn precious little about his background: only that he showed up six years earlier looking for work at a Los Angeles garage run by Shannon (Bryan Cranston), a nice guy with bad luck who is constantly reaching but rarely succeeding. Gosling’s character, referred to in the credits as the Driver, is a natural with mechanics and a genius behind the wheel. In addition to working in the garage, he makes money of the side stunt-driving in Hollywood films by day and working as a wheelman for various criminals by night. Like the gunslingers of western lore, he lives and works by a strict code of his own devising: He doesn’t carry a gun, he doesn’t get involved in whatever criminal activity is taking place, and all he promises is five minutes of driving, during which time he will do everything possible to get out clean. We see him in action during the film’s opening sequence, and it is a thrilling, brilliantly choreographed piece of work that draws us immediately into his experience behind the wheel and stirs questions about what is going on behind his rigid façade. The Driver’s regimented life is thrown for a loop when he becomes involved with Irene (Carey Mulligan), a quiet young mother who lives down the hall in his nondescript apartment building. Irene has an adolescent son named Benicio (Kaden Leos) whose father, Standard (Oscar Isaac), is released from prison just as she and the Driver are starting the tentative first steps toward developing a relationship. Standard is not free from his previous life, though, as he owes protection money that he must pay back by robbing a pawn shop. The Driver agrees to be the wheelman in order to help Standard escape his criminal obligations and settle down and be a proper husband and father, but the deal goes terribly wrong and the Driver finds himself on the wrong side of a pair of mobsters (Ron Perlman, always a solid choice, and, in an interested bit of against-the-grain casting, Albert Brooks). It just so happens that these two mobsters are also loaning money to Shannon to build a formula racecar that the Driver will helm, so his multiple worlds end up colliding in consistently unexpected ways. The screenplay, taken from a 2005 novel by the multi-talented crime writer, poet, and musician James Sallis, was written by Hossein Amini, who is better known for adapting classic tragic novels, including James Hardy’s Jude (directed by Michael Winterbottom in 1996) and Henry James’s The Wings of the Dove (directed by Iain Softley in 1997). Amini strips the story down to its bare bones and renders its emotional layers with a minimum of dialogue, which allows Refn to engage in moments of pure, unencumbered cinema. From a narrative perspective, Drive is a straight-up genre picture, one whose story components, characters, and themes are plenty familiar from any number of B-movies and programmers dating back to the era of film noir. Its cinematic godfather is Jean-Pierre Melville, the American-obsessed French director whose nuanced portraits of professional criminals in the 1960s and ’70s perfected the template for the criminal cool. At the same time, Drive is also inflected with the neon vibe and synthesizer rhythms of early Michal Mann films like Thief (1981) and Manhunter (1986). But, even when Drive threatens to become a familiar amalgam of European art cinema and traditional Hollywood criminality, Refn deftly and even audaciously elevates the routine with measured doses of formal brilliance, some of which enhances the film’s gritty, bloody realism and some of which takes it into poetic flights of fancy. In the film’s most memorable moments, Refn achieves both, such as a scene in an elevator where the Driver and Irene indulge in a lengthy, long-delayed kiss that seems to literally stop time, and the reverie is broken only when the Driver pulls away and viciously, excessively stomps in the skull of a hitman sent to kill them. The sudden shift from an expressively lit, dreamlike romantic moment to a shocking explosion of the most physical kind of violence is jarring and frankly shocking, but also key to the film’s effectiveness. The Driver is an enigma not just because we know so little about his background (no pat psychological explanations here), but also because Gosling imbues him with a ferocity that is matched only by his tenderness; we are drawn to him because we sense his soul, but he propels us away from him when the carnage is unleashed. It is shocking precisely because it defamiliarizes a traditional action movie trope: the hero whose use of violence is legitimized by narrative necessity. When the Driver goes about his bloody business, we understand intuitively that he is playing the genre role to the hilt, enacting righteous vengeance on amoral goons and criminal lowlifes, but the excessive manner in which he does it blows the lid off our security and confronts us with our own complacency. Copyright ©2011 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © FilmDistrict |

Overall Rating:

(4)

(4)