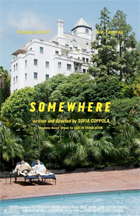

Somewhere

|  Somewhere, Sofia Coppola’s fourth feature, is a continuation of her cinematic exploration of personal isolation, and while it has much about it that is admirable, it will undoubtedly be experienced most directly as an inferior variation on Lost in Translation (2003), her Oscar-winning sophomore film that found beauty and quiet tragedy in the unlikely relationship between a fading movie star and a sad newlywed visiting Tokyo. In some ways the comparison is unfair, especially if you take seriously Jean Renoir’s assertion that directors make the same movie over and over again. However, Coppola does virtually everything imaginable to tempt us into seeing them as not just companion pieces, but riffs on many of the same exact themes and scenarios, which were also present to varying degrees in her other two films, her 1999 debut The Virgin Suicides and her unjustly criticized revisionist historical drama Marie Antoinette (2006). Somewhere, Sofia Coppola’s fourth feature, is a continuation of her cinematic exploration of personal isolation, and while it has much about it that is admirable, it will undoubtedly be experienced most directly as an inferior variation on Lost in Translation (2003), her Oscar-winning sophomore film that found beauty and quiet tragedy in the unlikely relationship between a fading movie star and a sad newlywed visiting Tokyo. In some ways the comparison is unfair, especially if you take seriously Jean Renoir’s assertion that directors make the same movie over and over again. However, Coppola does virtually everything imaginable to tempt us into seeing them as not just companion pieces, but riffs on many of the same exact themes and scenarios, which were also present to varying degrees in her other two films, her 1999 debut The Virgin Suicides and her unjustly criticized revisionist historical drama Marie Antoinette (2006).Coppola has an eye and an ear for isolation and loneliness, and she fixes her characters in worlds from which they are fundamentally cut off, whether it be the pomp and circumstance of the pre-revolutionary French aristocracy or the social battlegrounds of adolescent Americana in the ’70s. In this case, we are in the world of modern Hollywood royalty (which Coppola should know well as the daughter of director Francis Ford Coppola), which is seen as not so much a den of sin as a pit of existential angst. There is plenty of good ol’ fashioned fornication, but it is done with such dim nonchalance, such a lack of passion or intensity, that it takes on an air of the sad and the pathetic, even as it is ostensibly cloaked in privilege and wealth. The protagonist is Johnny Marco (Stephen Dorff), an A-list Hollywood actor who lives alone in a suite at the Chateau Marmont, the West Hollywood hotel on Sunset Boulevard that has been called home by everyone from Great Garbo to Keanu Reeves and is thought to be the inspiration for The Eagles’ “Hotel California.” Although the stuff of legend, Coppola presents the hotel as an island of lost souls, with Marco’s being the most lost of all (we are introduced to him driving his shiny black Ferrari in interminable circles in the middle of the desert, an apt visual metaphor for his moneyed, but aimless existence). As she did in Lost in Translation, Coppola establishes a rhythm of existence that is both completely naturalistic and highly stylized via relatively low camera angles and an almost insistently static frame. The routines of Johnny’s day have a certain dry regularity, even as we recognize that they are available to only a small percentage of the population. We see him working, but only shilling for his latest action movie, an activity that he does with little effort and no real interest. He has friends, but no one with whom he can genuinely talk, and he regularly receives text message from an anonymous someone to whom he did a great wrong. His relationship with women is problematic, to say the least, epitomized by his dozing off during a sexual encounter and the iciness with which a former costar greets him during a photo op. Even his lackadaisical watching of a pair of private stripteases in his hotel room suggests that he has transcended the traditional male sin of seeing women as objects and now barely sees them at all. None of this fazes Johnny or knocks a kink in his routine, and we get the sense that he is so removed from his own existence that individual days have no meaning. That begins to change with the arrival of Cleo (Elle Fanning), his 11-year-old daughter. He sees Cleo on an irregular basis (he’s an absent father in every sense of the phrase), but one day Cleo’s mother decides to disappear for a while, dumping her with Johnny for a few weeks. This might be considered a disruption for many people, but Johnny takes it in stride, folding Cleo into his daily routines and making her a part of his life. As a result, he begins to awaken, a process that Coppola allows to unfold in small, nuanced ways. Somewhere is not the kind of film where characters make grand speeches about their realizations or have teary breakdowns in which they confess to another character the film’s big message. Instead, Coppola packs meaning into small actions or seemingly benign scenes that in any other film would immediately hit the cutting room floor. Even seemingly large developments, like Johnny and Cleo traveling to Italy together for one of his press junkets, give us only small insights that we must piece together. The emotional trajectory of Johnny reconnecting with himself and his life via time spent with his innocent daughter is the very definition of cliché, but Coppola puts her own spin on it, using it as fodder for social observation. This demands quite a bit from Stephen Dorff and Elle Fanning because they don’t get big, actorly moments; rather, they must convey their characters through narratively insignificant events like playing Guitar Hero, swimming in the pool, and sharing a hamburger. Of course, as good as Somewhere is in its best moments, it ultimately feels too derivative for its own good, with the specter of Lost in Translation hovering over its every nuance. It doesn’t help that Coppola recycles some of that film’s most memorable traits, including the sense of dislocation one feels when watching familiar television programming in a foreign language and a crucial bit of dialogue in the end that is effectively withheld from our ears (in this case due to helicopter noise). Yet, even with that baggage, Somewhere develops its own emotional steam, carrying us along with the characters to a recognition of how important are the people in our lives that we so often take for granted. Johnny is not so much redeemed as he is shaken back into awareness, an important distinction that keeps the film from sliding into either the mushy or the preachy. Copyright ©2010 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Focus Features |

Overall Rating:

(3)

(3)