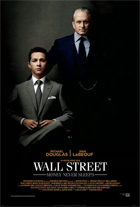

Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps

|  A decade ago, Oliver Stone was the premiere cinematic chronicler of the recent American past. No filmmaker better nailed the anxieties and failed dreams of the 1960s and, more importantly, the remorse that followed, than Stone did in Platoon (1986), Born on the Fourth of July (1989), JFK (1991), and Nixon (1995). Yet, as much as he looked to the past, there has always been a streak of the here-and-now in Stone’s work, beginning with his sophomore film Salvador (1986), which was a rare Hollywood exposé of Reagan-era tragedies south of the border, and Wall Street (1987), his morality tale about the temptations of money and power in the concrete jungle of New York City. Now, perhaps as a response to his grand failure to recreate the ancient past in Alexander (2004), Stone has recreated himself almost exclusively as a chronicler of the American present, as demonstrated in World Trade Center (2006), a sentimental depiction of individual heroism and fortitude on 9/11, and W. (2008), a tonally confused semi-satire of the Dubya years. A decade ago, Oliver Stone was the premiere cinematic chronicler of the recent American past. No filmmaker better nailed the anxieties and failed dreams of the 1960s and, more importantly, the remorse that followed, than Stone did in Platoon (1986), Born on the Fourth of July (1989), JFK (1991), and Nixon (1995). Yet, as much as he looked to the past, there has always been a streak of the here-and-now in Stone’s work, beginning with his sophomore film Salvador (1986), which was a rare Hollywood exposé of Reagan-era tragedies south of the border, and Wall Street (1987), his morality tale about the temptations of money and power in the concrete jungle of New York City. Now, perhaps as a response to his grand failure to recreate the ancient past in Alexander (2004), Stone has recreated himself almost exclusively as a chronicler of the American present, as demonstrated in World Trade Center (2006), a sentimental depiction of individual heroism and fortitude on 9/11, and W. (2008), a tonally confused semi-satire of the Dubya years.Thus, it is not surprising that he would accept the challenge of shaping a sequel to Wall Street that recasts that film’s “Greed is good” ethos within the context of the recent economic meltdown and government bailouts. The majority of Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps is set in 2008, just before the Wall Street crash, and the halls of power are still corrupt, except now everything is bigger and the stakes are higher. The original film’s charming anti-hero Gordon Gekko, a ruthless corporate raider played by Michael Douglas, is now on the margins of the financial world, touting a new book he has written that predicts the impending economic collapse. Gekko’s forced absence from “the game” due to an eight-year prison sentence for financial malfeasance has caused him to reassess his life and principles, which is visually reflected in his stylish, yet casually messy head of hair and lack of power ties. When we first see him getting out of prison in the film’s opening sequence (set in 2001), he has the air of a man defeated and at a loss for his place in the world; the intent is clearly to instill sympathy for a former shark who may now be well out of his depth. Yet, as with the original Wall Street, Money Never Sleeps is not really about Gekko; screenwriters Allan Loeb and Stephen Schiff simply resurrect him as a symbol of a bygone era to suggest that what was once so equally fearsome and attractive about him (and, by proxy, the free-market world of financial excess) has long since been surpassed by a new generation of mega-sharks whose lack of scruples makes Gekko’s Reagan-era wheeling and dealing look like playtime (something that Gekko readily admits). Also like the first film, Loeb and Schiff structure Money Never Sleeps as a morality tale with an ambitious, but fundamentally decent young man at the center. In this case it is Jake Moore (Shia LaBeouf), a successful financier who is trying to sustain investments in a new fusion technology that could potentially turn seawater into a source of clean energy. Like Bud Fox, the Charlie Sheen character from the first film, Jake is a mixture of idealism and aspiration whose dreams of making the big bucks are inextricably intertwined with a desire to do something good with them. Yet, such desires make him vulnerable, and Jake is constantly in danger of getting sucked into a worldview that prizes power and accumulation above everything. His initial mentor and father figure Louis Zabel (Frank Langella) is a dinosaur who knows that his time has come, and the tragedy of his end stokes Jake’s ambitions even more. He sets his sights on the ruthless mega-financier Bretton James (Josh Brolin), for whom he eventually goes to work. Bretton is the Gekko of the 21st century--harder and less charming--and Brolin plays him as a man of such rampant ego that he is almost inhuman. When he answer Jake’s question “What do you want?” with a single word--“More”--he effectively summarizes the fundamental problem with pure capitalism: There is never enough. Jake is also engaged to Gekko’s estranged daughter Winnie (Carey Mulligan), who runs a left-leaning blog about politics and the environment and holds fast to a massive grudge against her old man, for whom she blames the breakdown of her family and her older brother’s lethal drug overdose. Jake can’t help but be drawn to Gekko, partly because he wants to help Winnie reconcile with him and partly because he is fascinated with his future father-in-law’s sharp economic insight and notoriety. Behind Winnie’s back Gekko becomes a second father figure to Jake, nurturing his aspirations. There is, of course, always the question of what Gekko is getting out of the relationship, a question that he poses to Jake within 10 minutes of their first meeting. The underlying tension in Money Never Sleeps hinges on whether or not Gekko is truly a reformed man, or if he is still the same old shark, just lying in wait for the right opportunity to reclaim his throne. The question for the audience is whether or not we even want to see a reformed Gordon Gekko. When Stone is plying this tension, Money Never Sleeps is an engrossing drama of both interpersonal struggle and the dangers of material temptation, which reach as far as Jake’s mother (Susan Sarandon), a former nurse who was drawn into the quick-money world of real estate and is now constantly borrowing money from her son to keep her fragile dreams alive. At its best, the film illustrates with great clarity how money and its accumulation is its own drug (Gekko likens it to a needy, demanding woman that is always one step away from the door, a casually misogynistic metaphor that suggests his inherent limitations as a good guy). Yet, Stone frequently trips the film up on idiosyncratic visual devices and shifting tones that make one wonder if he is making a serious drama or a slightly veiled satire (Gekko being handed his brick of a cell phone as he leaves prison is a telling and sloppy mistake; it makes for a good wink-wink joke, but makes no actual sense given that cell phones had decreased in a size substantially by 1993 when he entered the pen). Stone loads the film with irritating transition devices like sped-up photography, overlapping images, and at one point an old-fashioned iris, none of which draw us into the story, but rather misdirect our attention from substance to style. Stone also mishandles several opportunities, especially Charlie Sheen’s brief cameo as Bud Fox at a massive fundraiser; the self-congratulating nature of Sheen’s performance makes it feel like a joke, and we never for a second sense that this is the character 20 years later. It’s a small fumble, but one that is indicative of the fact that Money Never Sleeps, for all its hear-and-now relevance, ultimately lacks the strength of character needed to draw us into its complex portrait of economic power. Copyright ©2010 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © 20th Century Fox |

Overall Rating:

(2.5)

(2.5)