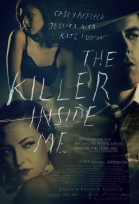

The Killer Inside Me

|  Of all the films based on the novels of postwar hard-boiled novelist Jim Thompson, whose body of work Meredith Brody described in Film Comment as “the most disturbing and the most darkly sadistic of the tough-guy writers,” Michael Winterbottom’s The Killer Inside Me is probably the most faithful to its source, which explains why it was met with boos and walkabouts earlier this year at the Berlin Film Festival. Although Thompson scripted several television episodes and also worked (contentiously, as it turned out) with Stanley Kubrick on The Killing (1956) and Paths of Glory (1957), only two of his novels were made into films during his lifetime: The Getaway (1972), a Steve McQueen/Ali Graw vanity project directed by Sam Peckinpah, and a low-budget version of The Killer Inside Me made in 1976, the year before Thompson died. Although he always wanted to break into Hollywood, Thompson’s novels were too dark and violent in their unrelenting portraits of irredeemable psychopathic protagonists to make the transition to the big screen. As Jospeh Bevan put it in a recent article in Sight & Sound, “He tended towards extremism and squalor. The warped nature of his characters was far from ideal for Hollywood: Thompson wasn’t so much hardboiled as cracked.” Of all the films based on the novels of postwar hard-boiled novelist Jim Thompson, whose body of work Meredith Brody described in Film Comment as “the most disturbing and the most darkly sadistic of the tough-guy writers,” Michael Winterbottom’s The Killer Inside Me is probably the most faithful to its source, which explains why it was met with boos and walkabouts earlier this year at the Berlin Film Festival. Although Thompson scripted several television episodes and also worked (contentiously, as it turned out) with Stanley Kubrick on The Killing (1956) and Paths of Glory (1957), only two of his novels were made into films during his lifetime: The Getaway (1972), a Steve McQueen/Ali Graw vanity project directed by Sam Peckinpah, and a low-budget version of The Killer Inside Me made in 1976, the year before Thompson died. Although he always wanted to break into Hollywood, Thompson’s novels were too dark and violent in their unrelenting portraits of irredeemable psychopathic protagonists to make the transition to the big screen. As Jospeh Bevan put it in a recent article in Sight & Sound, “He tended towards extremism and squalor. The warped nature of his characters was far from ideal for Hollywood: Thompson wasn’t so much hardboiled as cracked.”“Cracked” is a perfect description of Winterbottom’s uneven, but fascinatingly nasty adaptation of Thompson’s 1952 novel (possible his most disturbing), which maintains the author’s unapologetic savagery in depicting a chillingly self-aware psychopath and, with only a few exceptions, avoids any gloss or irony or distance. Largely unappreciated during his lifetime despite a prolific output of writing, Thompson’s star has risen in the literary world in the years since his death, and filmmakers as diverse as Bertrand Tavernier, Stephen Frears, James Foley, and Roger Donaldson have adapted his work to the big screen with varying levels of success. However, Winterbottom, who is known for his willingness to experiment, take on “impossible projects,” and transgress boundaries, is particularly well suited to translate Thompson’s spare, hardened prose into visual imagery, and your response to The Killer Inside Me may very well be determined by how willing you are to go with him into the abyss of a character who is essentially nonexistent, a man who is so fundamentally hollow inside--morally, spiritually, humanly empty--that he might as well not exist. He is close in spirit to American Psycho’s Patrick Bateman, who looked in the mirror and declared that he is “not there.” The story takes place in a small, but booming oil town in the Texas panhandle in the early 1950s. The protagonist and narrator of the story (the first-person “Me” in the title) is Lou Ford (Casey Affleck), an amiable 29-year-old deputy sheriff with a seemingly gentle disposition and innate sense of politeness. Born and raised in that same town, he’s so confident in its lack of crime that he doesn’t even both to carry a gun with him. He is a familiar, trusted face, and his longtime girlfriend, Amy Stanton (Kate Hudson), is considered “one of the finest ladies” in town. However, as the title blatantly tells us, Lou is not the unassuming good ol’ boy he appears to be, and he harbors a dark interior that is just waiting to be unleashed by the right stimulus, which comes in the form of Joyce Lakeland (Jessica Alba), a local prostitute whose sadomasochistic sexual tendencies tunnel a direct pipeline into Lou’s worst tendencies, which we learn as the film progresses were formed at an early age. Things start turning ugly when Lou gets caught in the middle of a backroom political struggle between Joe Rothman (Elias Koteas), the head of the local union, and Chester Conway (Ned Beatty), the owner of a large construction company that built half the town. Through a complex series of events, Lou ends going in with Joyce on a scheme to blackmail Chester’s son Elmer (Jay R. Ferguson), although he has a different and much more vicious plan to enact, which results in multiple murders of which he is sure he will not be suspected because of his great reputation. The town sheriff, Bob Maples (Tom Bower), an amiable but borderline incompetent drunk who sees himself as a kind of father figure to Lou, takes his story at face value, but Howard Hendricks (Simon Baker), the county’s dogged district attorney, isn’t so sure. As noir stories tend to go, there is no such thing as the perfect plan, and soon Lou is at the center of an escalating spiral of murder to cover up previous murders. Which, of course, brings us to the film’s most contentious issue: its uncompromisingly brutal depiction of violence, particularly male-on-female violence, which has led some critics to level charges of misogyny against the film, not only because of its ferocity, but because the two female victims are depicted as having sexually enjoyed violence on some level and might therefore be understood as having “asked for it.” There is no dismissing the impact of the film’s viciousness, which is as disturbing and graphic as Thompson’s original prose (he describes the face of a beating victim in the novel as being like “stew meat”), although much of the effect is not a result of on-screen imagery, but rather the drawn-out nature of the violence, the use of sound, and the behavior of the character inflicting it. We have become accustomed to graphic violence in the cinema, mostly because it is made palatable via association with either justifiably righteous characters or villains who we feel comfortably assured will get their due diligence at a later point. Winterbottom upends that notion and strips the violence of its comforts, which is why he can unnerve us so pointedly with only fleeting glimpses of actual physical contact and the gory results. When we watch Lou’s violence, it sickens us not because of what we see, but because of what we understand about his character: He is absolutely remorseless in his actions, and the fact that it is directed primarily against women is indicative of both the genre in which Thompson was writing (the worst punishment in hard-boiled pulp fiction was always reserved for the fairer sex) and also Thompson’s interest in psychoanalysis, which is used in both the novel and the film to explain Lou’s psychosis via his twisted childhood experiences with an older woman (in the novel it is his father’s housekeeper, but in the film it seems to be his mother). Thus, for Lou, all women are but one entity with the same face, but to charge the film with misogyny is to mistake the character’s perspective for the filmmaker’s, which are decidedly different. While Lou is certainly a character capable of exerting power and influence, he is ultimately a nasty, pathetic little man, bound by his own psychopathy and destined for a terrible demise because the killer inside him refuses to back down. We are never asked to sympathize with Lou, even though we are asked to understand that he is a paradox, a man who is not in control of himself and is unable to understand why. Although Casey Affleck’s stellar performance invites identification at the beginning of the film, his boyish politeness and affable nature are quickly revealed as thin disguises for his chilling lack of humanity, and by the end we despise him not because he’s evil, but because he is impossible to truly understand. He is cold, indifferent, illegible--thus, truly monstrous. In this regard, Winterbottom perhaps doesn’t go quite far enough, as there are several points in the film (particularly its fiery, near apocalyptic climax) that he scores with jangly swing music of the era, which creates an immediate sense of ironic distance despite the period appropriateness. Perhaps these moments were needed to pull us back out of the darkness, but in a film that is otherwise this unrelenting in its descent, is there really any point? Copyright ©2010 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Roadside Attractions |

Overall Rating:

(3)

(3)