Cruising

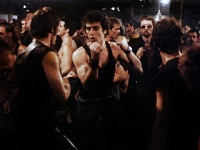

|  In the almost twenty years since it bombed in initial theatrical release, the critical response to William Friedkin's "Cruising" has done something of a complete 180-degree turnaround. Back in 1980, the homosexual press viciously lambasted it for presenting a truncated, negative portrait of gay life. However, in recent years it has suddenly been embraced as being pro-gay, having been unfairly criticized and stigmatized at the time of its release by well-meaning, but still hysterical opponents. Because nothing has changed about the film itself in the last twenty years, the re-evaluation of "Cruising" must be due to the changing cultural tides in America. In the almost twenty years since it bombed in initial theatrical release, the critical response to William Friedkin's "Cruising" has done something of a complete 180-degree turnaround. Back in 1980, the homosexual press viciously lambasted it for presenting a truncated, negative portrait of gay life. However, in recent years it has suddenly been embraced as being pro-gay, having been unfairly criticized and stigmatized at the time of its release by well-meaning, but still hysterical opponents. Because nothing has changed about the film itself in the last twenty years, the re-evaluation of "Cruising" must be due to the changing cultural tides in America.Today's mainstream cultural views are drastically different from those in 1980 when Ronald Reagan was first entering the White House, the majority of suburban Americans had never heard of Robert Mapplethorpe, and AIDS was still an unknown disease across the ocean. Some argue those were better times, while others see it as a repressive, conservative era that suppressed minority groups and restricted human expression. Now, at the end of the 1990s, it seems to me that the contemporary acceptance of "Cruising" has to do with the fact that homosexuals are enjoying more even-handed portrayals in the mass media than they were in 1980--they are less afraid of letting others see the dark side of their lifestyle because the positives are more readily available to balance them out. Remember, the critics back then didn't argue that Friedkin was presenting an incorrect portrait of gay life, but rather that he was focusing entirely on only the most fringe and potentially negative aspect of homosexual life, the one aspect the general populace would have the most trouble accepting. The majority of "Cruising" takes place in the leather-clad S&M homosexual underworld of New York City. A naive, twenty-something cop named Steve Burns (Al Pacino) is given a chance to move up to the rank of detective if he accepts the assignment of going undercover in the seedy nightlife in order to ferret out a serial killer who is preying on homosexual men. Burns takes the assignment and, in the process, begins to lose his previously rigid sexual identity, which means that his relationship with his girlfriend, Nancy (Karen Allen), begins to sour, and he becomes more and more infatuated with his gay neighbor, Ted (Don Scardino), an aspiring playwright who represents the film's one concession to a mainstream homosexuality. As a thriller and police procedural, "Cruising" is dull at best, inept at worst. Friedkin, who did such a fantastic job revving audience engines with "The French Connection" in 1971, has written and directed a mystery that is not only dense and confusing, but oftentimes utterly unbelievable. The idea of dropping a young, seemingly inexperienced cop like Burns in the middle of an important investigation tied to political ramifications with absolutely no leads, hoping that he attracts the killer because he physically resembles the previous victims, is a bit ludicrous. There's also a positively ridiculous interrogation scene that involves a large black man wearing nothing but a jock strap and a cowboy hat slapping around the suspect; the scene is so unexpected and absurd that it reaches the highest levels of camp. Some have argued that the point of this scene is to indict the police as heartless homophobes, but if that were really the intention, did the scene have to involve a burly, half-naked man who seemingly comes out of nowhere? Couldn't regular detectives dish out the brutality without incorporating their own variation of S&M? After all, the film makes the point much better in an early scene in which two patrolmen drive by late at night, commenting on how much they hate all the gays they see on the sidewalk ("They're all scumbags," one says. "All of 'em."). That part of the scene works on its own as an indication of general animosity among the police, but Friedkin pushes the scene further by having the cops force a couple of gay prostitutes in the car, then intimidate one of them into performing oral sex. Here, the indictment becomes vicious, suggesting that these cops are not only spiteful, but they are also self-loathing hypocrites. This same pseudo-Freudian theme works its way into the serial killer's character, as his unhealthy relationship with his unaccepting father is shoehorned via a silly flashback into explaining his murderous behavior. Friedkin's script leaves numerous untied ends, some of which are purposeful, some of which seem accidental. Chief among these is the ambiguous ending scenes, which show Burns continuing to frequent gay bars even after the serial killer has been caught, and a last-minute murder that possibly suggests Burns as the killer. The only thematic conclusion one can draw from the ending is that the exposure to the gay underworld has not only confused Burns' sexual identity, but also made him into a wrathful killer. The fact that the only other character who logically would have committed the final murder is also gay seems to further connect violence and homosexuality. Which, of course, leaves us with the question of why critics have begun seeing positive traits in a film that was once so scorned. Watching the film, you quickly get a sense of its perpetual ugliness--this is a thoroughly unpleasant film. For anyone of any sexual orientation who takes pride in fidelity, the scenes that take place in S&M bars bearing such enticing names as "The Cockpit" and "Ramrod" are positively repulsive. One can see why some of the mainstream gay critics in 1980 were horrified that a large segment of the population would see this film and incorrectly assume that all homosexuals behave in this manner. On the other hand, this sadomasochistic lifestyle did exist and still does, and thus there is no reason why it can't be used as a backdrop or even the main focus of a film. Of course, how it is used is a whole other story.... These sequences are like the cliché of every straight male's worst nightmare: an endless parade of brawny, bearded men dressed in a wide assortment of leather, chains, and spandex, sweatily groping each other amid the smoke and clamor. They are nameless men looking for short-lived physical experience to substitute for whatever else is lacking in their lives, casually displaying different colored bandannas in their pockets to advertise what they are willing to do. If these scenes seem uncannily realistic, it's because Friedkin didn't hire regular extras. Instead, he hired, in the words of editor Bud Smith, "the real thing." And "the real thing" is definitely on display. Numerous times, the camera takes on a life of its own, calmly panning the atmosphere, voyeuristically soaking up the libidinous interplay. Heavy kissing, fondling, gyrating, fellatio, and even one scene where a man is greasing up his whole arm for a little "fisting" of another man who appears to be strapped down--nothing is left unexplored. Unfortunately, while these sequences are rich in gritty detail, they don't help us understand the characters any better. In fact, they come off more like intentional shockers than purposeful explorations of a subculture. Whatever your feelings about the implications "Cruising" makes about homosexuality, the plain fact is that it is a badly made film. The fact that Pacino's character is sketchily drawn makes his later transformation hard to read and unmoving. We know absolutely nothing about Steve Burns at the beginning of the film, and we know almost nothing about him at the end. The fact that Pacino's performance is sullen and lacking in energy does not help matters. Friedkin's script, as noted earlier, leaves some aspects of the story unresolved. It was based on a novel by Gerald Walker, which supposedly makes the connection between Burns and the serial killer much clearer and more thematically satisfying. In translating the book into a script, Friedkin drops the connection between the two characters almost entirely, thus rendering the last half of the film unbearably dull because we know who the serial killer is, thus we lose the only enjoyable aspect of the narrative: solving the mystery. Thus, lacking in character, suspense, and clarity, and filled with ugly, degrading images, "Cruising" is a deeply flawed, painful film to watch, whose only consequence lies in the relative importance of the scandal it caused twenty years ago. Copyright © 1999 James Kendrick |

Overall Rating:  (1)

(1)